Lower left is a corner of Haneda Airport. Photo courtesy of Tokyo Bureau of Port and Harbor.

by Philbert Ono, updated: May 5, 2023

Overview of Japan’s cruise ship ports.

Being a stretched-out archipelago with a long coastline (34,600 km or 21,500 mi.) and hundreds of inhabited islands, Japan has many sea ports and harbors mostly for cargo/container ships and commercial fishing. Over 99 percent of Japan’s international trade volume is transported by ship.

Ports are also used by luxury cruise ships, ferries, tour boats, commuter boats, U.S. and Japanese navy ships, and the Japan Coast Guard.

On this page:

- Cruise ship departure ports

- Japan’s popular ports of call

- Shore excursions

- Mega-ships and harbor bridges

- Japanese port history

- Port town songs

- Major Japanese ports: Yokohama | Tokyo | Kobe | Hakodate | Nagoya | Kanazawa | Toyama | Amami-Oshima Naze | Yakushima Miyanoura

Japan has four categories of ports and harbors: International Container Hubs (5), Major International Ports (18), Major Ports (102), and Regional Ports (807). Most ports are managed by the local prefectural or municipal government. Japanese ports have seen remarkable development and expansion through land reclamation in the last 100+ years.

As of July 2017, the following Japanese ports were designated as “international cruise hubs” to have a dock dedicated to cruise ships: Yokohama Port, Shimizu Port, Shimonoseki Port, Sasebo Port, Yatsushiro Port, Kagoshima Port, Naha Port, Motobu Port, and Hirara Port (Okinawa). Tokyo Port and Kobe Port already have a cruise ship dock.

The larger ports are typically on or near the mouth of a large river. Heavy industries also tend to be near large ports to receive raw materials and send out finished products by ship. Tokyo Bay and other major bays are lined with large industrial belts along the waterfront.

Cruise ship ports and terminals

Preceded by ocean liner docks and terminals in the 1950s, cruise ship docks and terminals at Japanese ports are a relatively recent development. From the late 1980s and early 1990s, more international cruise ships started visiting Japan and luxury cruising gained traction in the Japanese market. There was a need for more cruise ship terminals.

Japan started to build new cruise ship terminals from the 1990s. Tokyo’s first cruise ship terminal with CIQ (Customs, Immigration, and Quarantine) was built in 1991 in Harumi. (Since replaced by Tokyo International Cruise Terminal in Odaiba in 2021.) Yokohama Port rebuilt its cruise ship terminal on Osanbashi Pier in 2002. And Kobe Port’s international terminal built in 1970 was renovated in 2015.

New cruise terminals have also been recently built at Kanazawa Port (Ishikawa Prefecture), Maizuru Port (northern Kyoto Prefecture), Sasebo Cruise Center in Uragashira (near Huis Ten Bosch), and Kochi Shinko Port in Shikoku. Also, Osaka Port (Tempozan) is replacing its cruise terminal building with a new one to open in April 2024 as Tempozan Cruise Terminal.

Cruise terminals are large spaces with CIQ facilities, gift shops and restaurants, PCR testing facilities, and passenger waiting areas. The majority of Japanese ports have only a flat dock for cruise ships.

Cruise ship departure ports

Japan’s main departure ports for cruise ships are Yokohama and Kobe, followed by ports in other major urban areas including Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Kanazawa, Shimonoseki, Hakata, Sasebo, Nagasaki, and Hakodate.

Cruise ships favor Yokohama and Kobe over Tokyo and Osaka, respectively, because they are both closer to the mouth of the bay and Pacific Ocean.

Note that Yokohama and Tokyo Ports are not the same. They are in the same region of Japan, but in totally different locations. Avoid saying “Yokohama/Tokyo” for your departure or arrival port. It’s confusing and ambiguous. Is it Tokyo or is it Yokohama? If your ship will arrive in Yokohama, don’t say “Tokyo” and vice versa. Better to write, “Yokohama (near Tokyo)” instead.

Most people in Japan need not travel far to get to the nearest departure port. If you’re already in Japan, there’s usually no need to lodge at the port city the night before unless you’re really faraway. The cruise departure time is typically in the late afternoon. You should have enough time to get there on the same day.

Japan’s popular ports of call as of 2019

In 2019, out of 142 Japanese ports visited by Japanese and international cruise ships, the most popular ports of call were as follows (in order of popularity):

1. Naha (260 visits), 2. Hakata, 3. Yokohama, 4. Nagasaki, 5. Ishigaki, 6. Hirara (Miyako, Okinawa), 7. Kobe, 8. Kagoshima, 9. Sasebo, 10. Osaka, 11. Hiroshima, 12. Miyajima, 13. Sakai (Osaka), 14. Kanazawa, 15. Hakodate, 16. Shimizu (Shizuoka), 17. Nagoya (Aichi), 18. Tokyo, 19. Maizuru (northern Kyoto), 20. Kochi, 21. Omishima (Ehime), 22. Otaru (Hokkaido), 23. Aomori, 24. Fukuyama, 25. Takamatsu, 26. Shimonoseki, 27. Uno, 28. Akita, 29. Beppu, 30. Naze (Amami Oshima, Kagoshima), 30. Kita-Kyushu, 31. Yatsushiro (Kumamoto), 32. Miyanoura (Yakushima, Kagoshima). 32. Naoshima, 33. Futami (Ogasawara, Tokyo), 34. Kushiro, 34. Sendai-Shiogama, 35. Niigata

*Source: 2019 cruise survey by Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

*English: http://www.wave.or.jp/jcpa/area/info/ACTUAL_PORT_CALL.pdf

Okinawa finally reopened its ports to cruise ships in late June 2022 after a 28-month closure since February 2020. Okinawa has had one of the highest rates of coronavirus infections in Japan. Being Japan’s most popular port of call, it was sorely missed by cruise ships.

Many local Japanese port authorities want to attract cruise ships or more of them. One success story is Kochi Shinko Port conveniently located in southern Shikoku which started accepting cruise ships in May 2014 when more international cruise ships started visiting Japan. It was enough for them to open the new Kochi Cruise Terminal on March 29, 2019.

Kochi then quickly became one of Japan’s Top 20 ports of call by 2019. However, locals point out that the ships don’t stay long enough for passengers to see more of the sights. They don’t spend much money either since lodging and meals are provided by the ship. This is true for most ports of call and it may become an enduring issue.

Shore excursions

Whichever port of call your cruise ship visits in Japan, you can be sure there will be lots to see. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be stopping there.

However, since cruise ships don’t stay long in port, you won’t have much time to tour on shore. The ship will usually have multiple shore excursions at the same time, and you have to choose only one. It can be a hard decision ending with a promise to “visit again someday.”

The main attraction of luxury cruising supposed to be the ship itself. The ports of call are actually only secondary. If you want more sightseeing time or if you think spending days at sea is a waste of time because you’re not seeing any sights on land, you’d better also include time for land-based tours.

If you plan to go ashore on your own, read up on the port. Each port is different. Some ports have tourist attractions right near the port, a short walk from your ship. Major ports may also have a train/subway station nearby. Other ports might not have anything nearby, so it might be best to go on the ship’s guided tour.

If you need a taxi, you should request one in advance. If you’re in a party of three or four, it might be cheaper to tour together by taxi instead of going on the cruise ship’s shore excursion. Just make sure to get back to the ship in time. If you have to get back by 4:00 p.m., try to get back by at least 3:30 p.m.

Ports in major cities might also have volunteer tour guides who would be happy to take you around. Contact them in advance.

Rest assured that Japanese ports don’t have scammers, dishonest taxi drivers, etc., preying on cruise ship passengers. Security staff is always present on the pier when a cruise ship docks.

Japanese ports with tourist attractions within the immediate vicinity include Yokohama (Red Brick Warehouses, Minato Mirai, Yamashita Park, etc.), Kobe (Meriken Park, Kobe Port Tower, Sannomiya), Osaka (Tempozan Harbor Village, ferris wheel, aquarium), Nagoya (Nagoya Port Building, Maritime Museum, Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium, Fuji Antarctic Museum ship), Toyama (Kaiwo Maru museum ship), Nagasaki (Glover Garden), and Hakodate (Mashu Maru, Hakodate Station, morning market).

Note that out of Japan’s 47 prefectures, eight are landlocked with no ocean ports: Tochigi, Saitama, Yamanashi, Nagano, Gunma, Gifu, Shiga, and Nara. These prefectures might be too far from the nearest port of call for a shore excursion.

Mega-ships and harbor bridges

Many major Japanese ports inevitably have a bridge spanning across waterways to connect the many wharves over a wide area. Until the 1990s, the height of new harbor bridges in Japan were designed to be high enough (around 52 meters) for Queen Elizabeth 2 to pass under. QE2 was the largest luxury passenger ship at the time. However, mega-ships 60 to 70 meters high soon appeared.

At Port of Tokyo in the 1990s, Rainbow Bridge was built high enough for QE2 to pass under. Ironically though, the QE2 never sailed under Rainbow Bridge. The bridge was also already too low for mega-ships.

Japan has since scrambled to accommodate mega-ships at alternate piers outside harbor bridges. Tokyo finally opened the new Tokyo International Cruise Terminal in September 2020 outside Rainbow Bridge to replace the old Harumi Passenger Ship Terminal (torn down in 2022) which required ships to pass under the bridge. The new terminal was completed in time for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, but no ships came due to the pandemic.

Also, Yokohama Port converted a cargo dock to open Daikoku Pier outside Yokohama Bay Bridge for mega-ships. Japan has learned the lesson to not build a cruise terminal requiring ships to sail under a bridge.

Upcoming needs

Japanese ports are still not equipped to supply LNG fuel (liquefied natural gas) and shoreside power to cruise ships. Mainly because Japanese cruise ships are not yet equipped for LNG or shoreside power. LNG reduces air pollution, and shoreside power also reduces emissions at the port city since the ship can turn off its fuel-guzzling power generators and be powered by the port city’s power grid instead.

More international cruise ships are using LNG and shoreside power. In spring 2025, Japan will finally have a new cruise ship partially fueled by LNG and compatible with shoreside power.

Asuka Cruises will receive the new cruise ship to be homeported in Yokohama. Maybe it will replace the Asuka II. Although Yokohama Port is currently not equipped to provide LNG and shoreside power to cruise ships, it is making plans to do so. It aims to be a carbon neutral port by 2050.

Japanese port history & ports in peril

Japan has been a seafaring nation since ancient times. Its earliest overseas voyages ventured to Korea and China. They were usually official envoys or tribute embassies to China from southern and western Japan such as Yamato province.

International voyages became especially frequent from the 6th century when cultural and religious exchanges between Japan and China/Korea began in earnest. Japanese scholars and priests sought to study Korean and Chinese culture, art, architecture, and religion (Buddhism). These expeditions had a profound influence on Japan.

One ancient port where their boats departed was Naniwa-tsu (難波津) in present-day Chuo Ward, Osaka. The boats would sail through Seto Inland Sea and then through the Kanmon Strait between Kyushu and Honshu before heading for Korea or China. Today, the precise location of Naniwa-tsu in Chuo Ward (now reclaimed land) is subject to scholarly debate.

From the 15th century, the port town of Sakai in Osaka flourished with foreign trade with China, Spain and Portugal calling on the port before Japan isolated itself from the world in the early 17th century.

During the Edo Period (1603–1867) when Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa samurai government headed by the shogun, only Dejima, a small fan-shaped island and foreign settlement in Nagasaki, allowed foreign contact and trade with the Portuguese and then the Dutch whose ships came right up to the island.

Dejima was shut down in 1859 when Japan opened its ports to the West beginning with America. Dejima today is no longer an island nor port, only a tourist attraction with some restored buildings. The city is working to restore more buildings and make it fan-shaped island again.

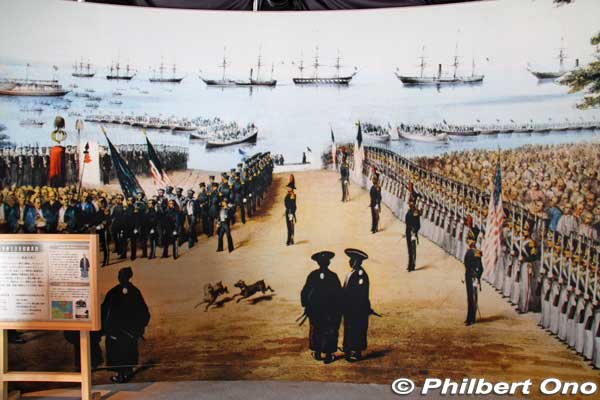

The opening of Japan started with Commodore Matthew C. Perry‘s shocking first visit to Japan in July 1853 with his menacing “Black Ships.” It was the beginning of an epoch-making historical development for Japanese ports (and the entire country).

While brandishing his navy guns during that first visit and a second visit in February 1854, Perry gave Japan’s samurai government no choice but to sign the Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity (Kanagawa Treaty) to open Shimoda (Shizuoka) and Hakodate Ports to American ships. The U.S. wanted Japan to allow their whaling ships into port to receive food, water, wood, and coal, and provide relief to any shipwrecked sailors.

This treaty ended Japan’s 250-year self isolation. Although Shimoda never developed into a major port like Hakodate did, it still has points of interest related to Japan-U.S. relations. The temple housing the first U.S. consulate where the first U.S. Consul General to Japan, Townsend Harris, lived and worked is still there.

The Kanagawa Treaty was still not enough for the Americans because Shimoda was too far from Tokyo (Edo). The U.S. soon had Japan sign the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the United States (Harris Treaty) in July 1858. This treaty opened Yokohama (Kanagawa) and Nagasaki, and later Niigata and Kobe (Hyogo) to American ships and allowed Americans to live at the treaty ports.

By the late 19th century and early 20th century, Yokohama and Kobe became Japan’s main ports for international trade. Yokohama shipped out silk and tea while receiving soybeans, wheat, cotton, and coal.

Both ports also became Japan’s international gateways for arriving foreigners and departing Japanese emigrant laborers moving to Hawaii, North America, and South America seeking jobs and a better life.

In the last 100 years, Japanese ports saw major development and major disasters, both natural and man-made.

On September 1, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake killed over 100,000 and inflicted heavy damage to Yokohama and Tokyo including the ports.

When the quake struck, three passenger ships were moored at Yokohama’s Osanbashi Pier. One of them was Canada-flagged RMS Empress of Australia which was just about to leave Yokohama. However, the pier collapsed and caught fire, trapping many people on the pier who were seeing off the ship.

The ship’s captain, Samuel Robinson, conducted rescue operations with ladders and ropes for people trapped on the dock to climb aboard. Lifeboats were also sent ashore to rescue people in need. The ship remained in Yokohama for 12 days to provide relief. She then took thousands of refugees to safety in Kobe. Captain Robinson was widely hailed as a hero in Japan and Canada.

A few other international ships in Yokohama also provided similar relief to people in need.

Both Yokohama and Tokyo Ports were rebuilt bigger and better than ever before. Osanbashi Pier was fully repaired by September 1925.

Typhoons have also wreaked havoc on ports and ships, usually during July to September. In September 1934, the powerful and deadly Muroto Typhoon (室戸台風) claimed over 3,000 lives and caused much damage especially to Shikoku, Kobe, and Osaka Bay. Muroto is the name of a cape in Kochi Prefecture where the typhoon landed.

Another destructive typhoon came in September 1959. Ise-wan (Ise Bay) Typhoon (Typhoon Vera) is still talked about today. Nagoya Port and Aichi Prefecture suffered some of the worst damage due to strong storm surges. Japan has been learning from all these typhoons and have made ports and harbors less susceptible.

World War II (1941–1945) still stands as the most devastating event for Japanese ports and the entire country. Ports were major targets for attack especially when they were next to factories or industrial belts. Most major Japanese ports including Tokyo, Yokohama, and Nagoya were completely disabled by May 1945 with numerous mines dropped by B-29s in bays, ports, and strategic waterways.

Many Japanese ships were sunk or damaged. Whether they were aircraft carriers, battleships, ferries, or passenger-cargo ships, Japan suffered catastrophic maritime losses.

Yokohama Port was bombed by three B-29s on April 24, 1945, Kobe Port was firebombed in June 1945 (photo), the steel factory in Kamaishi was bombarded by battleships on July 14, 1945, and Hachinohe Harbor came under attack in July 1945.

Hakodate and Aomori Ports were also major targets when all twelve Hakodate-Aomori Seikan train ferries in port or at sea were sunk or damaged on July 14–15, 1945 even with passengers and crew aboard (total 400+ victims).

The Seikan train ferries were a vital supply link from Hokkaido to Honshu, transporting trains loaded with coal and food. Coal was essential for military factories and power generation. (Also see “Port of Hakodate“.)

In Akita Prefecture on August 14, 1945, the night before the war ended, over 100 American B-29 bombers dropped over 12,000 bombs on Akita Port (Tsuchizaki) while targeting adjacent oil facilities. It was one of the last air raids of the war. Over 200 residents died. Unexploded bombs are still found in the area. (At least 127 duds have been found during port construction work.)

After World War II, Japan’s major ports came under the control of U.S. Occupation forces (GHQ) for military use. Even after the Occupation ended in 1951, parts of Kobe Port were still controlled by the U.S. for sending troops to the Korean War and Vietnam War. It wasn’t until 1974 when the Port of Kobe was fully returned to the city.

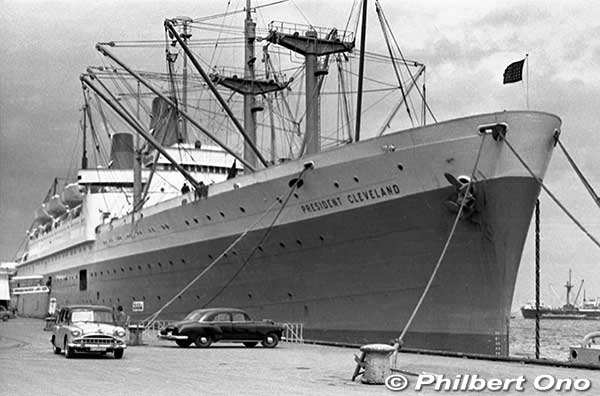

In Yokohama, Osanbashi Pier (called “South Pier” by the Americans) was returned in February 1952. Transpacific ocean liners such as SS President Cleveland, SS President Wilson, SS Himalaya, and SS Chusan then started docking at Osanbashi as cruise ships do today. Yokohama and Kobe Ports became Japan’s main international gateways during the 1950s.

However, Mizuho Pier, called “Yokohama North Dock” or “North Pier” by the Americans, with seven berths, is still used by the U.S. Army and Navy today. The city hopes to see this substantial chunk of pier returned.

From the early 1960s, passenger ship docks became less busy as air travel took off and ocean liners started to disappear. The outflow of Japanese emigrants also stopped as people could find jobs at home amid Japan’s high-growth period.

In 1972, Mitsui O.S.K. Passenger Line discontinued its routes to South America and converted an emigrant ship into a cruise ship named “Nippon Maru.” Later succeeded by a newer ship.

The number of visitors coming to Japan by ship peaked in 1970. The death knell was perhaps the Boeing 747 “jumbo jet” appearing in 1970 and carrying hundreds of passengers to make the trip to/from Japan a matter of hours instead of days.

Fortunately, Japan’s international passenger ship terminals soon had something to do again when international cruise ships (sometimes converted from ocean liners) like the Royal Viking Star, SS Canberra, and SS Rotterdam started to visit from the 1970s.

In March 1975, luxury ocean liner Queen Elizabeth 2 called on Japan for the first time during her maiden world cruise. She visited Kobe and then passed by a snow-capped Mt. Fuji before reaching Yokohama with 1,400 passengers.

At Osanbashi Pier, a whopping 520,000 people came to see QE2 during her four days in port. She then sailed on to Honolulu where she also received many oohs and ahhs. QE2 visited Yokohama 19 more times until 2008.

She was the most famous and admired passenger ship in the world. A massive and beautiful ship she was for her time, bearing the most famous and charismatic British name. (Now a floating hotel in Dubai.)

Japan has had an affinity with British royalty through the Japanese Imperial family which has long maintained a closeness with the British monarchy. The recent passing of the beloved Queen has been noted by many in Japan.

From the 1980s, many Japanese ports started to establish sister-port relations with overseas ports. There are also friendship port cities. Here’s a small sample of sister-port relations for major Japanese ports.

| Port | Sister Ports | Friendship Ports |

| Yokohama | Oakland, CA; Vancouver; and Hamburg | Shanghai and Dalian, China |

| Tokyo | New York/New Jersey Port; Los Angeles, and Rotterdam, Holland | Tianjin, China |

| Kobe | Seattle, WA; Rotterdam, Holland | |

| Osaka | San Francisco, Melbourne, Busan, Le Havre (France), Valparaíso (Chile), and Saigon | |

| Nagoya | Los Angeles, Baltimore, Freemantle (Australia), Sydney, Antwerp | |

| Hakata | Auckland, New Zealand | Shanghai and Guangzhou, China |

By the late 1980s, luxury cruising caught on overseas, maybe thanks to “The Love Boat” TV series in the U.S. This spurred three Japanese maritime companies to get serious in the luxury cruise business. The year 1989 is hailed as the dawn or starting year of cruise ships in Japan. Passenger buzz finally returned to Japanese ports.

However, Japan remains a disaster-prone country. Besides typhoons, there are earthquakes (and sometimes tsunami).

The Port of Kobe got a major setback when the Great Hanshin Earthquake struck on January 17, 1995, killing over 6,000 residents and destroying much of the port. Within several days though, at least one pier was reopened to enable volunteers and provisions to reach Kobe from Osaka port. Cruise ships also came to provide relief and accommodations.

Kobe Port was soon rebuilt. In June 1995, an international cruise ship (Kareliya from Ukraine) arrived in Kobe for the first time since the quake and docked at Shinko Pier No. 1. Heavily damaged Kobe Port Terminal dedicated to cruise ships was also repaired and the Fuji Maru docked in July 1996.

Little did we know that an even more disastrous earthquake (and tsunami) would occur only 16 years later. One that supposed to occur only once every thousand years. How could it happen so soon after a major quake in Kobe? No one expected it.

The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami on March 11, 2011 destroyed most ports along the eastern coast of the Tohoku Region (Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, Fukushima, and Ibaraki Prefectures). From Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture to northern Ibaraki Prefecture, ports and piers were washed away or in shambles. They included Miyako, Kamaishi, Sendai Shiogama, Ishinomaki, Kesennuma, and Ofunato Ports. Sendai Port had ship containers scattered about.

Ninety percent of fishing boats in Tohoku were damaged. Within 10 days, the major ports underwent makeshift repairs to enable ships to bring provisions and fuel. By March 2012, 106 of 126 berths (84 percent) at ten Tohoku ports were in use again.

Within two years after the quake, about 90 percent of Tohoku piers became usable again. The Japanese government also instituted better countermeasures at ports and harbors against tsunami and earthquakes with improved breakwaters, earthquake resistance, and disaster response.

Such major earthquakes (and tsunami) also forced cruise ships to cancel cruises.

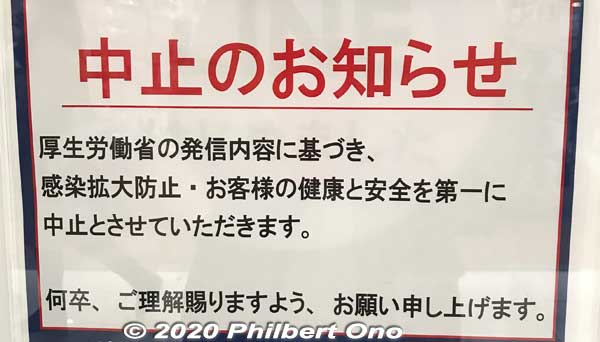

Almost 10 years later, another calamity named COVID-19 from February 2020 forced cruise ships to suspend operations for months. This also affected ports which remained lonely and empty.

New cruise terminals at Tokyo, Kanazawa, and Sasebo lay almost unused. Tokyo’s spanking new cruise terminal was completed in time for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics for cruise ships to dock as floating hotels during the Games. But the building lay empty throughout the Games. Such a pity.

Until late 2022, Japanese cruise ships were biding their time with domestic cruises until they can cruise overseas again.

On Nov. 15, 2022, Japan’s Ministry of Transport finally announced that Japan will reopen to international cruise ships. From March 2023, international cruise ships restarted cruises to Japan in droves. They include the MS Amadea, Diamond Princess, and the MS Westerdam. Japanese ports have been giving a big welcome to overseas cruise ships and passengers.

Port town songs

Japanese port towns have been featured in popular Japanese songs. The most famous and enduring port town song is the 1969 mega-hit Minato-machi Blues (Port Town Blues 港町ブルース) by Mori Shin’ichi (森進一). The song mentions many famous Japanese port towns including Hakodate, Kamaishi, Kochi, Beppu, Makurazaki, Takamatsu, and Kagoshima. See the videos below.

Essential Japanese Vocabulary – Ports (Click to open)

Compiled by Philbert Ono, updated: Sept. 7, 2022

port – minato 港

port of call – kikōchi 寄港地

call on a port – kikō suru 寄港する

pier – sanbashi 桟橋

pier/dock/wharf – futō 埠頭

dock or dockside – ganpeki 岸壁

arrive at port – nyūkō 入港

leave port – shukkō 出港

set sail – shukkō 出航

boat/ship – fune 船

board the boat – jōsen 乗船

disembark – gesen 下船

depart and return to Yokohama – Yokohama hatchaku 横浜発着

boat entering the port – irifune 入船

boat leaving the port – defune 出船

boat returning home – kaeri-bune 帰り船

boat separating you and someone on board (farewell parting) – wakare-bune 別れ船

Shinko – 新港 literally meaning “New Port,” this is a common term used at large ports having many piers to indicate the newest port dock. For example, Toyama Shinko Port and Shinko Pier at Yokohama Port.

home port – bokō 母港

at port, docked – teihakuchū 停泊中

moor – keiryū 係留

hawser – ホーサー thick rope to moor the boat

bollard – bit ビット or bollard ボラード (係船柱)

port town/city, harbor city – minato-machi 港町

bay – wan 湾

terminal – terminal ターミナル

CIQ (Customs Immigration Quarantine) – CIQ

Customs – zeikan – 税関

Immigration – shutsu-nyūkoku kanri 出入国管理

Quarantine – ken’eki 検疫

land – rikuchi 陸地

final port (during a cruise) – kichaku-kō 帰着港

tender boat – tsusen 通船

go ashore – jōriku 上陸

shore excursions – optional tours オプショナルツアー or kikōchi kankō 寄港地観光、

tour bus – kankō bus 観光バス

tour on your own on shore – jiyu kōdō 自由行動

return to the boat – kisen 帰船

time to return to the boat – saishu kisen jikoku 最終帰船時刻

Next: Port of Yokohama | Port of Kobe

Content Navigator

Ports for Cruise Ships in Japan (Current page)

- Cruise ship departure ports

- Japan’s popular ports of call

- Shore excursions

- Mega-ships and harbor bridges

- Japanese port history

- Port town songs

- Major Japanese Ports: Yokohama | Tokyo | Kobe | Hakodate | Nagoya | Kanazawa | Toyama | Amami-Oshima Naze | Yakushima Miyanoura

- Ship comparison

- Japanese cruise ship advantages

- COVID-19 protocols

- Basic cruise rules

- Safety Record

- FAQ

- Asuka II

- Nippon Maru

- Pacific Venus

State of Japanese Cruise Industry in mid-2022

- COVID-19 not over yet

- International cruise ships in Japan

- Japan still closed to international cruising

- Essential Japanese Vocabulary