Robert Walker Irwin

by Philbert Ono, Updated Sept. 22, 2014

|

| A young Robert Walker Irwin |

|

| Robert Walker Irwin in later years |

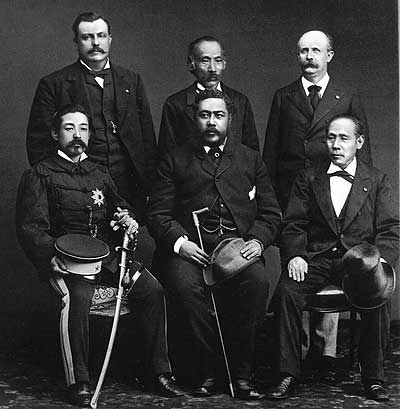

Robert Walker Irwin (ロバート・ウォーカー・アルウィン) (1844-1925) was an American businessman from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA who lived in Tokyo, Japan and was the Hawaiian Minister to Japan and Special Agent and Special Commissioner of Hawai'i's Board of Immigration. Representing the Kingdom of Hawai'i, he headed the negotiation and management of the government-contracted Japanese immigration to Hawai'i during 1885-1894 called Kanyaku Imin (官約移民).

In Japan, he is called the Father of Japanese Immigration to Hawai'i, along with King David Kalakaua who encouraged Japanese immigration to Hawai'i. Irwin also had a summer home in Ikaho, a hot spring town in Gunma Prefecture. Part of the house is now preserved as a small museum. This is Ikaho's Hawai'i connection and reason for its sister-city ties with the Big Island of Hawai'i since 1997.

Irwin hailed from a very distinguished family lineage, on both his mother's and father's sides. Through his mother, Sophia Arabella Bache of Philadelphia, he was a direct descendant of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. His mother was a fourth-generation direct descendant, descending from Benjamin Franklin's daughter Sarah (1743-1808) who married a Richard Bache.

Irwin was born on Jan. 4, 1844 in Copenhagen, Denmark as the third son (and one of six children) of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania native William Wallace Irwin (1803-1856) who was the United States Chargé d’Affaires to Denmark from March 3, 1843, to June 12, 1847. William was also the mayor of Pittsburgh in 1840-41, and elected as a Whig to the Twenty-seventh Congress (March 4, 1841-March 3, 1843) representing Pennsylvania. William was a descendant of a Scottish king (Malcolm II).

The family moved to Philadelphia in 1850 when Robert was 6 years old. His older brother Richard found Robert (while still in high school) a job at the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Robert headed the company's San Francisco office and was later assigned to head the Yokohama office. At age 22, Robert arrived Japan on Jan. 6, 1866. In 1865, the company had been awarded a contract by the US government for monthly mail service between San Francisco and Hong Kong via Hawai'i and Japan. The company started operating trans-Pacific steamship service between San Francisco, Hong Kong, and Yokohama from 1867.

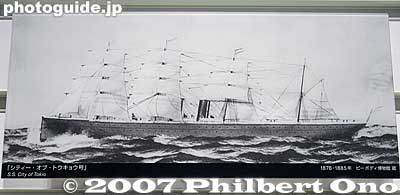

The company later built (in 1874 in Chester, PA) and operated the City of Tokio, the steamship which would bring the first Japanese immigrants to Hawai'i in 1885 under the Kanyaku Imin program. (A few months after that historic voyage, the ship in foggy weather ran aground on some rocks near Yokohama in June 1885 and was soon destroyed by a typhoon.)

Irwin later worked for other employers such as trading company Mitsui Bussan when it was founded in 1876. He also invested in companies in Japan and Taiwan. His involvement with Mitsui was through his personal friendship with Count Inoue Kaoru (井上 馨) and Masuda Takashi (益田 孝) who both founded trading company Mitsui Bussan (and its forerunner company) which later became the core company of the Mitsui Zaibatsu conglomerate. Count Inoue Kaoru was a major figure in the Meiji government and Japan's Foreign Minister during 1879-1887. In this capacity, Inoue served as the main man in the Japanese government handling the Japanese immigration opposite Irwin. Irwin was thus well-connected in both business and government in Japan.

In 1880, Irwin was appointed as the Kingdom of Hawai'i's Consul-General in Japan. In March 1881, during a trip to Japan, Hawai'i's King David Kalakaua promoted Irwin to Hawaiian Minister to Japan. Interestingly, Irwin was not from Hawai'i and had never lived there even though he was Hawai'i's top representative to Japan.

Irwin married a Japanese woman, Takechi Iki (武智イキ), on March 15, 1882. She came from a samurai family. The marriage was arranged by Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru who searched for and found the bride for his good friend. International marriages in those days were still very rare in Japan, and it took a good amount of paperwork and time before the marriage was processed. In Nov. 1883, their first child and eldest daughter, Sophia Arabella "Bella" Irwin was born in Tokyo. She was followed by five more children (three daughters Mary, Marion and Agnes; and two sons Robert II and Richard). Even while living in Japan for many years, Irwin could hardly speak Japanese and always had an interpreter. He spoke to his wife in broken English and broken Japanese. To his children (who were educated in both Japan and the US), he spoke English. Being a successful businessman, married to a Japanese, and well-liked in Japan, Irwin was well-positioned to help negotiate, plan, and manage the government-sponsored Japanese immigration to Hawai'i.

Kanyaku Imin 官約移民

By the 1870s, the Kingdom of Hawai'i's native population was in serious and tragic decline ever since the white man introduced diseases to which the natives had no immunity. Leprosy was also taking its toll. In 1876, Hawai'i's population was only 55,500. The two top priorities of King David Kalakaua's administration was to increase the native population (with "cognate races") and to advance agriculture and commerce. Besides increasing Hawai'i's permanent population, they needed to secure more laborers to work in the sugar cane fields. The only answer was immigration to Hawai'i from abroad.

Immigration to Hawai'i started in earnest from 1876 when immigrants from various countries in Asia (India and China), the South Pacific islands, Portuguese islands (Madeira and Azores), and even Europe (Norway and Germany) were brought to Hawai'i. The most numerous were the Chinese. They came to be too numerous with too many men and far too few women. Their large numbers caused various social problems and anti-Chinese sentiments, and restrictions were eventually placed on Chinese immigration. This created a labor shortage again.

Hawai'i then looked to Japan. Japanese immigrants had been on Hawai'i's mind for years. As early as June 19, 1868, 153 Japanese immigrants, called Gannen-mono (元年者) (First-Year People, since it was the first year of the Meiji Era), came to Hawai'i as private (not sanctioned by the government) contract laborers. They were sent by American businessman Eugene Van Reed. They were hardworking and well-behaved, giving the Japanese a good reputation as a source of immigrants to serve as laborers and help repopulate the kingdom. But they were treated poorly by the sugar planters, and the Japanese government became concerned.

The Japanese government was slow in responding to Hawai'i's immigration proposals due to its own domestic problems and concerns over their citizens being mistreated. The immigration issue later hinged on Japan's success in first revising unfair treaties with other Western powers. The Hawaiian government could not wait that long and kept negotiating and sending envoys to Japan.

In March 1881 when King Kalakaua visited Japan during his world tour, he struck up a personal friendship with Emperor Meiji. He even proposed that his beloved six-year-old niece Princess Kaiulani be betrothed to a Japanese prince who had impressed the king. (The proposal was later politely declined.) The subject of immigration was also brought up. The king expressed that the Hawaiian government wanted to increase its population by inviting immigrants from other countries. And that any Japanese who desired to settle in Hawai'i would be permitted to do so.

In Nov. 1882, the highly-regarded former Maui governor John M. Kapena, a native Hawaiian, was sent to Tokyo instructed to emphasize racial affinity between Hawaii and Japan and to encourage Japanese immigration. At a dinner in Tokyo, he gave an amazing speech:

"His Majesty (Kalakaua) believes that the Japanese and Hawaiians spring from one cognate race and this enchances his love for you. He hopes that our people will more and more be brought closer together in a common brotherhood. Hawaii holds out her loving hand and heart to Japan and desires that Your People may come and cast in their lots with ours and repeople our Island Home — with a race which is sent to us by His Imperial Majesty, Your government and people may blend with ours and produce a new and vigorous nation making our land the garden spot of the Eastern Pacific, as your beautiful and glorious county is of the Western.” (From The Hawaiian Kingdom 1874-1893, by Ralph Kuykendall)

Kapena also met with Foreign Affairs Minister Inoue Kaoru and stated terms and conditions (including wages) proposed by the Hawaiian government for Japanese immigrants. Kapena duly impressed the Japanese, but Japan still was not ready to allow immigration to Hawaii.

In March 1883, Irwin was appointed Special Commissioner for Japanese immigration and was entrusted to continue immigration negotiations with Japan. To help Irwin, another native Hawaiian, Colonel Curtis Piehi Iaukea, was sent to Japan in April 1884 as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary. Iaukea met with Irwin, Foreign Minister Inoue, and even the emperor. He stated Hawai'i's proposed terms and conditions for immigration. Although Inoue declined to conclude an immigration treaty at this time, he told Iaukea that Japan would not block any immigration to Hawai'i. This tacit approval finally put Hawai'i's Japanese immigration plans in motion.

It so happened that Japan was facing a major economic recession and discontent among farmers in Japan. Giving them the option of going to Hawaii might relieve some of the domestic stress.

On Jan. 27, 1885, the first group of 943 Japanese immigrants under the Kanyaku Imin program ("Kan" means government, "yaku" means contract, and "Imin" is immigration) departed Yokohama and arrived Honolulu on Feb. 8, 1885 aboard the Pacific Mail Steamship City of Tokio. They were 676 men, 159 women, and 108 children who had free passage, expenses paid by the Hawaiian government. Their monthly wage was $9 for the men, and $6 for the women. They would also receive a food allowance, free housing, and free medical care. They were to work 10 hours a day and 26 days per month. It was a three-year contract with the Hawaiian government.

Irwin accompanied this first group of Japanese. The immigrants received a grand welcome in Honolulu under the direction of King Kalakaua. The Royal Hawaiian Band played, and policemen served as tour guides. A few days later on Feb. 11, 1885, the Japanese immigrants returned the gracious welcome by demonstrating kendo fencing, fireman's acrobatics on an upright ladder, and the intriguing sport of sumo which Irwin explained to the King and the rest of the audience. They even wore makeshift kesho mawashi ceremonial aprons (made of blankets) and performed the ring-entering ceremony. The event was capped by drinking and offering barrels of sahke to the audience. The sake was apparently brought aboard together with the immigrants, arranged by Irwin or the King.

Irwin did all he could to make the Japanese immigration a success. He sought to educate Hawaiian officials and sugar plantation agents and owners about the Japanese immigrants. He made a list of excellent suggestions for managing the Japanese laborers. This memo was circulated among the Board of Immigration and the plantation employers. And in Japan, he kept the Japanese government and people informed about the situation in Hawai'i. (Unfortunately, some plantations were still excessively harsh on the immigrants, prompting some of the laborers to stop working within a month.)

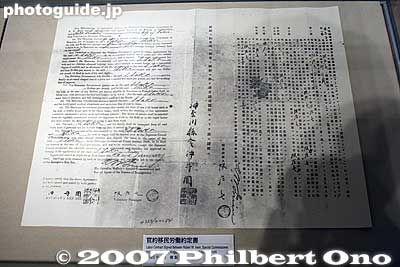

|

| Bilingual (English on left, Japanese on right) Kanyaku Imin labor contract signed by R.W. Irwin as Hawaii's Special Agent and Special Commissioner of the Board of Immigration and an immigrant named Saka Shoshichi in Jan. 1885 (facsimile exhibited at the Japanese Overseas Migration Museum in Yokohama). |

|

| ''City of Tokio'' steamship (picture exhibited at the Japanese Overseas Migration Museum in Yokohama) |

Irwin went back to Japan and returned to Hawai'i a few months later with the second shipload of Japanese immigrants arriving Honolulu on June 17, 1885 on the Yamashiro Maru (山城丸). They were 930 men, 34 women, and 14 children.

On Jan. 28, 1886, after Japan was rest assured that its citizens in Hawaii would be treated fairly, a formal immigration treaty between Japan and Hawaii was finally signed by Japan in Tokyo. The treaty stipulated that all Japanese immigrants would go to Hawai'i under a contract not exceeding three years, signed at Yokohama by the Special Agent (Irwin) of Hawai'i's Board of Immigration, the immigrant concerned, and subject to approval by the Governor of Kanagawa.

The Hawaiian government would be held responsible for the employer's treatment of the immigrants and the faithful execution of the contract. The Hawaiian government would also provide free transportation* from Yokohama to Honolulu on first-class passenger steamships and provide an adequate number of interpreters, inspectors, and Japanese physicians. The treaty would be valid for five years. (*This proved to be too expensive, so from the fourth shipload, the immigrants were made to bear part of the transportation cost, usually paid in monthly installments after they started working.)

On the Japanese side, the treaty conditions and negotiations were handled by Foreign Affairs Minister Inoue Kaoru who was already a personal friend of Irwin. He allowed Irwin to send a third shipload of Japanese immigrants who arrived Honolulu on Feb. 14, 1886 on the City of Peking (sister ship of the City of Tokio) operated by the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. Irwin was also on board with the immigration treaty for ratification by the Hawaiian government.

The door was thus opened wide for large-scale Japanese immigration to Hawaii sponsored by the governments of Japan and Hawaii. Immigrants from Yamaguchi and Hiroshima Prefectures developed an excellent reputation as laborers and more of them were recruited than anywhere else in Japan. The Kanyaku Imin immigration lasted from Feb. 8, 1885 to June 27, 1894. Although there were several interruptions due to arguments by the two governments over the terms and conditions, a total of twenty-six shiploads of immigrants brought around 29,000 Japanese men, women, and children during this period. For Irwin, it was a lucrative venture as he reportedly received a $5 commission for each adult male immigrant he recruited.

Over 7,000 Kanyaku Imin immigrants eventually returned to Japan by the end of 1894, still leaving over 20,000 Japanese in Hawai'i. This was 20 percent of Hawai'i's population. However, this was only the beginning. The bulk of Japanese immigration (including Okinawan immigration starting in 1900) occurred after this period through private channels up until 1924 when the U.S. Congress prohibited further immigration from Japan. By 1910, 40% of Hawai'i's population was Japanese, numbering almost 80,000. By 1924, over 200,000 Japanese immigrants had arrived in Hawai'i. It was a spectacularly successful effort to repopulate Hawai'i'. If you have ancestors who were Japanese immigrants to Hawai'i, find out what year they arrived in Hawai'i. Then you will know if they were part of the Gannen-mono (1868), Kanyaku Imin (1885-June 1894), or a private immigration scheme (July 1894-1924).

In 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act allowed immigration from Japan again. It also made the Issei eligible for naturalization.

Ikaho 伊香保

|

| Preserved summer residence of Robert W. Irwin in Ikaho, Gunma |

|

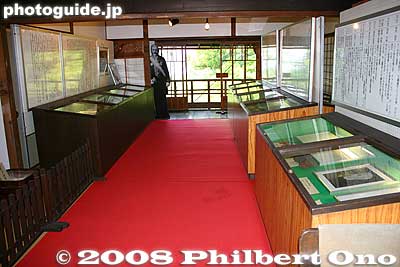

| Inside the summer residence of Robert W. Irwin in Ikaho. Served as a small museum until fall 2013 when it was relocated.More photos of the museum here. |

In 1891, upon the auspices of Count Inoue Kaoru, Irwin purchased a summer home in Ikaho, Gunma Prefecture to escape Japan's hot summers (Ikaho is now a part of the city of Shibukawa). He enjoyed the hot spring town's coolness and quiet. From then on until his death in 1925, he and his family spent every summer in Ikaho. The residence was also used by Irwin's staff and guests from Hawaii visiting Japan. Ikaho is a centuries-old hot spring town first established in the 16th century. During the Meiji Period in the late 19th century, it was an upscale hot spring resort frequented by famous novelists and artists like Natsume Soseki and Takehisa Yumeji as well as prominent foreigners. The Imperial family also had a summer home in Ikaho (now occupied by Gunma University).

Eldest daughter Bella Irwin (1883-1957) loved Ikaho and was popular there. Whenever she went for a walk, the neighborhood kids would follow her around. Eventually she invited them to the summer residence where she showed them picture books from abroad and offered sweets. It later became a teacher-student relationship as she started teaching the kids (and later adults) at the Ikaho residence. Upon the approval of her parents, she started a Christian Sunday School in Ikaho. To enhance her qualifications as a teacher, she later went to study preschool education in the US. However, Christian Sunday Schools were being persecuted in Japan, forcing Bella to close her Sunday School in Ikaho and lose the summer residence. She went to Tokyo where she established the Irwin Gakuen school and kindergarten アルウィン学園 in 1916 in Kojimachi. Today, the school is in Tokyo's Suginami Ward called Irwin Gakuen Gyokusei Hoiku Senmon Gakko アルウィン学園玉成保育専門学校 training students to become nursery school teachers. Bella never married and never had any children of her own.

On Oct. 1, 1985, to mark the 100th anniversary of the Kanyaku Imin, the town of Ikaho in Gunma Prefecture designated Irwin's former summer residence as one of the town's Historical Places (伊香保町指定史跡) and proceeded to preserve part of the residence which was moved to its present location. In return, Hawaii's Governor George Ariyoshi, a descendant of Japanese immigrants and America's first Japanese-American governor, sent a letter of appreciation to the town and people of Ikaho. The summer residence (called Hawai'i Koshi Bettei ハワイ公使別邸 or Robert W. Irwin Bettei ロバート・W・アルウィン別邸) opened to the public as a history museum of the Irwin family and Japanese immigration to Hawai'i (free admission). Located near the bottom of the famous Stone Steps until autumn 2013, the present house is only part of the original villa and not very large. Irwin's Ikaho residence was originally located on the land currently occupied by an inn called Kanzanso 観山荘 which is right in front of the bottom of the Stone Steps. Irwin's preserved home was adjacent to this inn until autumn 2013 when it was moved a short distance away slightly up the Stone Steps. Map here | Photos here. Address: Ikaho 29-5, Ikaho-cho, Shibukawa, Gunma Pref. How to get to Ikaho.

On Jan 22, 1997, citing its Hawai'i connection through the Irwin summer house, Ikaho established sister-city relations with the County of Hawai'i (island of Hawai'i). In the summer of that year, Ikaho started to hold the annual King Kalakaua "The Merrie Monarch" Hawaiian Festival featuring hula performances by numerous hula groups from various parts of Japan and Hawaiian workshops taught by a well-known kumu hula (recognized hula teacher) from Hawai'i.

The hula festival is held for a few days in August. The main highlight is a nightly hula performance by the overall winner of the Merrie Monarch Festival, the world's most prestigious and famous hula competition held in April in Hilo, Hawai'i. Hawai'i's top hula halau (hula school or troupe) is thus invited to Ikaho every summer. Ikaho's hula festival is officially sanctioned by the Merrie Monarch Festival. Every four years, the Hawaiian festival includes a hula competition judged by Merrie Monarch Festival judges. (The next competition is to be held in Aug. 2009.)

Among the many hula festivals in Japan, Ikaho's Hawaiian Festival is unique because it is organized by a municipal government (based on sister-city relations) instead of a private company. The Merrie Monarch refers to King David Kalakaua who revived hula dancing (suppressed by the missionaries) during his reign and liked to have fun.

For other Japanese-American museums in Japan, see Japanese-American and Nikkei Museums in Japan.

Robert Walker Irwin Chronology

|

| Robert Walker Irwin and wife Iki |

- 1844 Jan. 4: Born in Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 1850: Moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- 1866 Nov. 6: Arrives in Japan to staff the Japan branch of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Later he works for Walsh Hall & Co. ウォルシュ・ホール商会, an American trading firm in Yokohama whose founders (Walsh brothers) produced paper in Japan (morphing into Mitsubishi Paper Mills).

- 1873: Helps Count Inoue Kaoru establish the forerunner company (先収会社) of trading company Mitsui Bussan.

- 1874: David Kalakaua (1836-1891) is elected King of the Hawaiian Kingdom. He reigns until his death in 1891.

- 1876: Arranged a trip to the U.S. for Count Inoue Kaoru, his wife and daughter, and about twenty assistants and students where they arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in August during the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Irwin served as their guide in the U.S. Also starts working for Mitsui Bussan, a trading company established that year.

- 1880: Appointed as the Kingdom of Hawaii's Consul-General in Japan to succeed Harlan P. Lillibridge who resigned.

- 1881 March 1881: during a trip to Japan by Hawaii's King David Kalakaua, Kalakaua promotes Irwin to Hawaiian Minister to Japan.

- 1882: Awarded the 4th Class, Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette 勲四等旭日小綬章 by the Japanese government.

- 1882 March 15: Marries Takechi Iki 武智イキ as arranged by Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru.

- 1883 Mar. 10: Appointed by Hawaii as Special Commissioner for Japanese immigration.

- 1883: Becomes General Manager of Kyodo Unyu Kaisha 共同運輸会社, a shipping company which merged in 1885 to become Nippon Yusen (NYK Line).

- 1883 Nov.: First child and eldest daughter, Sophia Arabella "Bella" Irwin (1883-1957), born in Tokyo.

- 1884: Appointed as Special Agent of the Hawaiian Board of Immigration. Also traveled to Hawaii to discuss with the Hawaiian government, plans to start the Japanese immigration. While in Hawaii, he is appointed as Commissioner for Japanese immigration. He returns to Japan by the end of Aug.

- 1885 Feb 8: The first group of Japanese immigrants under the Kanyaku Imin program arrives Honolulu aboard the Pacific Mail Steamship City of Tokio. Irwin accompanies this first group.

- 1885 June 17: Irwin arrives Honolulu with the second group of 978 Japanese immigrants aboard the Yamashiro Maru.

- 1885: Awarded the 3rd Class, Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon 勲三等旭日中綬章 by the Japanese government.

- 1886 Feb. 14: The third group of Japanese immigrants arrive Honolulu on the City of Peking operated by the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. Irwin was also on board bringing the immigration treaty (signed by Japan on Jan. 28, 1886) for signing by the Hawaiian government.

- 1886: Awarded the 2nd Class, Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star 勲二等旭日重光章 by the Japanese government.

- 1891: Purchases a summer home in Ikaho, Gunma Prefecture where he then spends every summer.

- 1892: Awarded the 1st Class, Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure 勲一等瑞宝大綬章 by the Japanese government.

- 1894: Japanese immigration to Hawaii under the Kanyaku Imin government contract ends. The program brought a total of 29,339 Japanese immigrants to Hawaii. Japanese immigration continues in the private sector until 1924. Hawaii is also annexed to the U.S. in 1898, five years after the Hawaiian monarchy is overthrown by Americans.

- 1900: Together with Masuda Takashi 益田孝, establishes the Taiwan Sugar Company 台湾製糖株式会社 (later merges with Mitsui Sugar Co.).

- 1916: Resigns as advisor to the Taiwan Sugar Company. Eldest daughter Bella founds the Irwin Gakuen school and kindergarten アルウィン学園 in Kojimachi, Tokyo.

- 1925 Jan. 5: Dies of an illness at age 81. Buried at Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo. Awarded the 1st Class, Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Blossoms, Grand Cordon 勲一等旭日大綬章 by the Japanese government.

- 1985 Oct. 1: For the 100th anniversary of the Kanyaku Imin, the town of Ikaho in Gunma Prefecture designates Irwin's former summer residence as one of the town's Historical Places 伊香保町指定史跡 and proceeds to preserve part of the residence moved to its present location. Hawaii also celebrates the 100th anniversary with exhibitions and events.

- 1997: Citing its Hawaii connection through the Irwin summer residence, Ikaho establishes sister-city relations with the County of Hawaii (island of Hawaii) on Jan. 22. Ikaho starts to hold the annual King Kalakaua "The Merrie Monarch" Hawaiian Festival from that summer. (Ikaho township later merged with the neighboring city of Shibukawa on Feb. 20, 2006, making Shibukawa the sister city to the County of Hawaii.)

- 2006 Feb 20: Ikaho town merges with the city of Shibukawa in Gunma Prefecture.

- 2012 July 26: Granddaughter Yukiko Irwin donates two medals to the Japanese Overseas Migration Museum in Yokohama where they are on public display. One medal was awarded by King Kalakaua of Hawaii and the other was awarded by Emperor Meiji. (See photo.)

- 2013 autumn: The former Irwin summer residence is relocated slightly up the Stone Steps from the previous location next to the foot of the Stone Steps. Map here

- 2014 April: A "Guidance Facility" museum (ガイダンス施設) opens next to the relocated Irwin summer residence. The new museum displays artifacts and exhibits related to the Irwin family and emigration to Hawai'i. Artifacts previously exhibited in the Irwin summer residence are moved to the new museum. The second floor of the home is also opened to the public on weekends and national holidays.

About Irwin's siblings: Robert W. Irwin was one of six children of William Wallace Irwin. His older brother John Irwin (1832-1901) was a half brother born to William's previous wife. He became a Rear Admiral in the US Navy in 1891 and retired in 1894. Another elder brother, Richard Biddle, headed the London, UK office of Mitsui. His older sister Agnes Irwin (1841-1914) founded the Agnes Irwin School in 1869 in Philadelphia and was the first dean of Radcliffe College. The Agnes Irwin School still exists today as an all-girl, non-sectarian, day school for PreK-Grade 12. Perhaps Aunt Agnes was an influence on niece Bella who started a school of her own in Japan.

|

| Grave of Robert Walker Irwin and wife Iki at Aoyama Cemetery, Tokyo |

Note: In Japanese, his name is written as ロバート・ウォーカー・アルウィン. However, you might see "Irwin" written as アーウィン instead, which is more accurate pronunciation-wise, but apparently not the official spelling. "Irwin" is archaically rendered as アルウィン on the Kanyaku Imin labor contracts and Bella's school is アルウィン学園.

Author's Notes

Robert Walker Irwin first caught my attention when I visited Ikaho, Gunma for the first time in Aug. 2003 during its annual Hawaiian Hula Festival. There was a "Hawaiian Minister's House" and I promptly visited it. The house displayed much information about the Irwin family and Japanese immigration to Hawaii. It also had an informative pamphlet in Japanese about Irwin and the immigration. Unfortunately, nothing was in English. That was too bad because the hula dancers, musicians, and others from Hawaii were visiting the house during the Ikaho hula festival. (They can't read Japanese.) I have offered this article to be photocopied and made available at the Irwin house.

After visiting Ikaho, I tried to find more information about Robert Walker Irwin, and was disappointed that there was very little information despite the historical importance of this man. The most information I found about Irwin was at the Ikaho house and in the Hawaiian Kingdom history book by Ralph S. Kuykendall (see References below). A chapter in the book gives a good account of how the Japanese immigration was started and Irwin's role. But it does not delve into his life and dealings in Japan. Thus, I still have many unanswered questions.

Like what made him love Japan so much? When was his first contact with Hawaii? How did he meet Count Inoue and other bigwigs? I wonder if he ever kept a diary or journal of his life, especially during the time he was handling the Japanese immigration. And what happened to his descendants other than Bella and Yukiko Irwin (daughter of second son Richard)? I'm told Yukiko Irwin was in New York City working as a massage therapist as of several years ago.

It's incredible to find a man who apparently never lived in Hawaii to have been entrusted with such an important task and be involved so deeply with Hawaii and its future history. Ironically, it seems that he is better recognized and written about in Japan than in Hawaii. The Japanese government bestowed its highest awards (Order of the Rising Sun, etc.) on him multiple times. The Hawaiian government also awarded him multiple medals. Irwin may have been long forgotten after the much larger mass immigration occurring after the Kanyaku Imin. Nevertheless, Irwin was wealthy, and he made a fortune from the immigration program by charging a commission for each adult male he delivered to Hawaii. He continued to have successful business pursuits even after his immigration work was done. He lived a comfortable and privileged life in Japan.

I've been meaning to write this article about Irwin ever since visiting Ikaho in 2003. My motivation was increased after finding so little information about him. In spring 2008, I finally got around to it, as I spent a few days piecing together all the information I could find about him in the few English and Japanese sources at hand. It almost turned into an article about the Japanese immigration itself which I'm also tempted to write, but there's enough information about that already. I'm pretty satisfied with this article, but there are still unanswered questions as I mentioned above. And there might be additional sources of information which I haven't found yet. I look forward to that. Any new information, of course, will be added here. I think Irwin deserves more recognition in the English-speaking world. So here's my contribution to that end. I attended the Ikaho Hawaiian Festival in Aug. 2008 and I gave copies of this article to the people from Hawai'i and to people at the Shibukawa City Hall and tourist bureau. It was very well received by all.

|

| Taking advantage of its Hawaii connection via Irwin's summer home, Ikaho holds an annual Hawaiian Festival in early Aug. highlighted by top hula dancers from Hawaii. More photos of the hula show here. |

I have always had a personal interest in people who served to bridge Japan and Hawaii (or the US). Irwin really struck a chord in me. He had a project to bridge a gap between Japan and Hawaii, worked at it to fruition, and executed it. It must have been immensely satisfying to take up such a task and making it happen. But it must have been disappointing to later hear stories of how badly some of the Japanese laborers were being treated by the exploitive employers. He really cared about Japan-Hawaii relations and the Japanese people. And he did it without being proficient at Japanese. Amazing.

He was one of the key people helping to create a new breed called Japanese-Americans. His original goals of supplying laborers (Japanese later accounted for over 60% of sugar plantation workers) and repopulating Hawaii (by 1910, 40% of Hawaii's population was Japanese, numbering almost 80,000, the largest ethnic group) were spectacularly attained. I wish he had lived long enough to see how the Japanese eventually excelled in Hawaii and made huge advancements and contributions to these islands and to America itself.

Though I'm a Japanese-American from Hawaii, I'm not descended from Japanese immigrants. But I grew up with them and their descendants. How I wish I was old enough and curious enough to ask the issei generation about their immigration experiences. As a child, I can only remember them as being old and wrinkled, but kind and gentle. How I wish I could have thanked them for all their kindnesses as I grew up. And even the nisei generation who are now dying out, as parents, teachers, public servants, and guardians who took care of us directly, I thank them as well.

Major References

- Robert W. Irwin Bettei summer residence and pamphlet, Ikaho-cho Board of Education

- The Hawaiian Kingdom Volume III 1874-1893, The Kalakaua Dynasty, by Ralph S. Kuykendall, University of Hawaii Press, 1967

- Kanyaku Imin, A Hundred Years of Japanese Life in Hawaii, Edited by Leonard Lueras, International Savings and Loan Association Ltd., 1985

- Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands by Gavan Daws, University of Hawaii Press, 1974

- Around the World with a King, William N. Armstrong

- カラカウア王のニッポン仰天旅行記、ウィリアム・N. アームストロング (著), William N. Armstrong (原著), 荒俣 宏 (翻訳), 樋口 あやこ (翻訳)

- Cane Fires: The Anti-Japanese Movement in Hawaii, 1865-1945 By Gary Y. Okihiro, Temple University Press

- Japanese Overseas Migration Museum

- Irwin Gakuen Web site

- New York Times article archive

- Irwin summer residence by Shibukawa