In early February 2025, we went on a two-day bus tour of Fukushima Prefecture’s coastal towns near the stricken Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. It was to see the area’s ongoing recovery from the March 11, 2011 (at 2:46 pm) triple disaster (“3.11”) caused by the mega-earthquake, giant tsunami, and an “unthinkable” (想定外) but preventable nuclear disaster. Fukushima was the prefecture to suffer from all three disasters on a large scale. (福島県浜通り復興視察ツアー)

Although recovery is still far from complete, especially from the nuclear disaster (reactor decommissioning and landscape decontamination) and low population levels, Fukushima has come a very long way since the 3.11 disaster that wreaked pandemonium and mass panic, debris-filled disaster areas, radiation leaks, and mass evacuations fourteen years ago.

The earthquake damage and tsunami debris along coastal areas have been well cleaned up; all main roads and train lines/stations (JR Joban Line and Tohoku Shinkansen) have reopened since Dec. 2021 and March 2020 respectively; radiation levels are safe; new public housing, medical clinics, and schools have been built; and commercial activities have restarted at rebuilt fishing ports and shopping facilities. Overseas tourists visiting Fukushima Prefecture have recovered to pre-COVID levels (179,180 in 2023).

Although there are still restricted areas where decontamination and infrastructure reconstruction are ongoing, the public can travel freely by train, bus, car, or bicycle to pockets of habitable areas where there are things to see.

The Tohoku Region’s Pacific coast is now dotted with memorial museums, monuments, and remnants of the 3.11 disaster open to the public. We visited some of them.

Contents

- Fukushima’s three regions

- March 11, 2011 triple disaster in Fukushima

- Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant

- “Hope tourism” in Tohoku Region

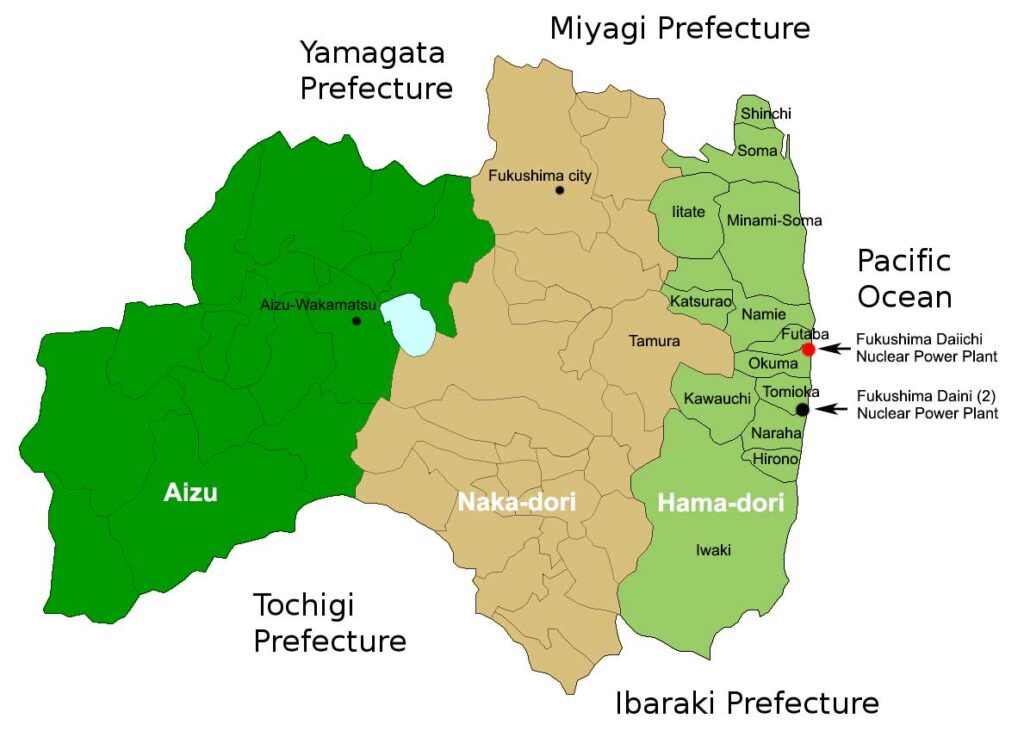

Fukushima’s three regions and coastal municipalities

Fukushima Prefecture is Japan’s third largest prefecture with the following three main geographical regions in the north-to-south orientation based on two mountain ranges and the Pacific Ocean.

- Hama-dori (浜通り) in light green is the coastal region along the Pacific coast consisting of small coastal cities, towns, and villages which suffered the most from the 3.11 disaster, especially from the tsunami and leaking nuclear power plant. This is where the stricken Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is located in Okuma and Futaba Towns.

Most people in this region were initially ordered to evacuate from the radiation threat. Evacuation orders were gradually lifted as the months and years passed.

From north to south, Hama-dori has Shinchi Town, Soma city, Minami-Soma city, Iitate Village, Katsurao Village, Namie Town, Futaba Town, Okuma Town, Tomioka Town, Kawauchi Village, Naraha Town, Hirono Town, and Iwaki city.

The 3.11 earthquake measured mostly M6- or M6+ in this region. Due to ongoing decontamination work and reconstruction of infrastructure, parts of Minami-Soma city, Iitate Village, Katsurao Village, Namie Town, Futaba Town, Okuma Town, Tomioka Town are still off limits as of March 2025. This is seven of the twelve municipalities originally ordered to evacuate after 3.11. (See https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/uploaded/attachment/606164.pdf) However, all these municipalities also have areas reopened to the public. Roads to restricted areas are gated, fenced, or guarded, so you can’t wander into a restricted area by mistake.

Within Hama-dori are two non-administrative districts Futaba-gun (双葉郡) and Soma-gun (相馬郡). Futaba-gun has Katsurao Village, Namie Town, Futaba Town, Okuma Town, Kawauchi Village, Tomioka Town, Naraha Town, and Hirono Town. And Soma-gun district has only Shinchi Town and Iitate Village. (Japan’s -gun districts do not include cities.)

There’s also the Soso sub-region (相双地域) consisting of all the cities, towns, and villages in Hama-dori except Iwaki which is a sub-region in itself.

The pre-disaster population of Hama-dori in 2010 was about 540,000. - Naka-dori (中通り) in beige is the central region with the Fukushima Basin in the middle of the prefecture between two mountain ranges, the Ou and Abukuma. It’s where most of the prefecture’s population live including capital city Fukushima. The Tohoku Shinkansen bullet train also runs through Naka-dori. The 3.11 earthquake here measured M5+ to M6- causing some damage to infrastructure, but no tsunami damage and almost no evacuation orders. (After 3.11, it took 49 days to completely repair earthquake damage along the Tohoku Shinkansen line.)

Naka-dori initially received many evacuees from Hama-dori and had to setup evacuation centers.

The pre-disaster population of Naka-dori in 2010 was about 1.2 million. - Aizu (会津) in dark green is the mountainous region in the west centering on Aizu-Wakamatsu, a famous castle town and major tourist spot, and Lake Inawashiro (light blue). It was least affected by the 3.11 disaster with the earthquake measuring only M4 to M5-. It sees quite a bit of snow in winter.

The pre-disaster population of Aizu region in 2010 was about 296,000.

These three geographical regions are often mentioned when referring to weather forecasts and earthquake magnitudes in Fukushima Prefecture.

All three regions are easily accessible via public transportation. Hama-dori has the JR Joban Line running between Tokyo and Sendai (Miyagi Prefecture) with train stations such as JR Futaba Station, JR Haranomachi Station, and JR Soma Station. In Naka-dori, Tohoku Shinkansen has Shin-Shirakawa, Koriyama, and Fukushima Stations in Fukushima.

March 11, 2011 triple disaster in Fukushima

The Great East Japan Earthquake (東北地方太平洋沖地震) aka 2011 Tohoku earthquake or “3.11” struck on March 11, 2011 at 2:46 pm. Although the earthquake’s epicenter measured M9 off the coast of Miyagi Prefecture (130 km east of Sendai), it decreased to mostly M5+ to M6+ by the time it rippled to Fukushima’s Hama-dori region. It was a long, powerful earthquake felt in most parts of Japan at various magnitudes.

Even in Tokyo, 373 km (232 mi) from the epicenter, it was M5+, strong enough to topple bookshelves and cupboards at home. Supermarkets were beset with broken glass and liquids fallen from shelves. Public transportation in Tokyo was also suspended, forcing many commuters to walk home that evening.

The frequent aftershocks all night were also frightening. Fortunately, damage to homes and buildings in Tokyo was none or minimal, except for neighborhoods affected by major liquefaction from the reclaimed land near the waterfront.

Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures soon got hit by giant tsunami waves as high as 8 to 21 meters. The tsunami arrived first on the coast of Iwate within 30 to 40 minutes after the earthquake and then to Fukushima within 40 to 70 minutes.

The tsunami in multiple waves by far caused most of the physical damage and loss of human life in all the affected prefectures.

Nuclear disaster

However, Fukushima suffered a third disaster with Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant’s nuclear reactors overheating after the earthquake knocked out the cooling system’s main power source. Although the backup power generators kicked in, they were soon flooded and disabled by the giant tsunami.

The reactor’s uncontrolled heat led to meltdowns and leakage of radioactive materials and hydrogen explosions in three of the reactor buildings. Although nuclear plant experts had long cited the cooling system as being vulnerable to major tsunami, plant management believed the probability of a major earthquake and tsunami occurring in the region was extremely low.

By the morning after 3.11, residents within a 20 km to 30 km radius of the power plant were ordered or recommended to evacuate. This covered most of Hama-dori. About 12 percent of Fukushima Prefecture’s area became a restricted zone. By May 2012, a total of 164,865 residents had evacuated.

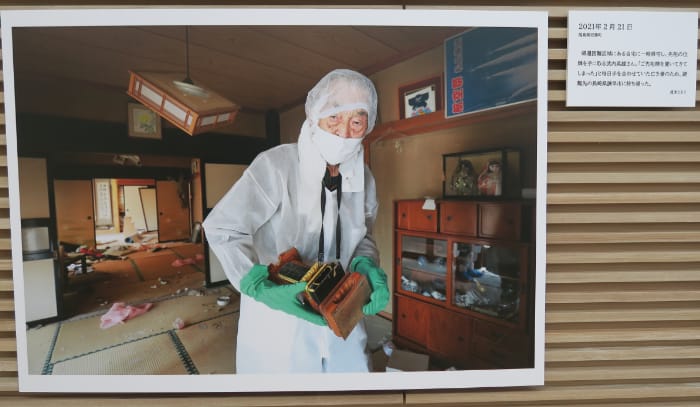

From May 2011, evacuees were allowed to return and visit their homes for a short period. Since radiation levels were still high, returning residents had to wear protective clothing. They were taken by bus to their restricted neighborhoods near the nuclear power plant. They were allowed to bring back only a bagful of personal effects which were also screened for radiation. It was also a chance for them to see their neighbors again.

As of February 2024, Fukushima Prefecture counted 1,614 deaths and 196 people missing due to the 3.11 earthquake and tsunami. Even after 14 years, local police, fire fighters, and Coast Guard occasionally rake the beaches in search of more missing people.

No one in Fukushima has been diagnosed with any illness caused by exposure to the 3.11 radiation. However, there are about 2,348 people who died of indirect causes such as poor health or stress from evacuations and those who could not receive medical treatment in time for underlying illnesses due to closed hospitals. This number exceeds the number of deaths and missing caused directly by the disasters. (Total deaths in the Tohoku Region is about 19,765 plus 2,553 people missing as of March 2023.)

As of August 1, 2024, Fukushima counted 15,483 homes totally destroyed and 83,640 partially damaged by 3.11.

Lifting of evacuation orders and compensation

As the years passed, radiation levels decreased naturally or by the decontamination of the landscape (topsoil and brush removal). After the reconstruction of vital infrastructure, evacuation orders started to be lifted in certain areas in Hama-dori from March 31, 2017. The further away the municipalities were from the Daiichi nuclear plant, the sooner their evacuation orders were lifted and the higher the percentage of returnees.

However, many evacuees had spent the interim years rebuilding their homes and lives elsewhere, making them decide to never return. Returning would be costly with the construction or purchase of yet another house back home to rebuild their lives for a second time.

Fukushima evacuees have been receiving various compensation from the government and TEPCO. It can be quite generous for nuclear disaster evacuees compared to tsunami evacuees who don’t receive much.

The compensation amount varies widely depending on how near/far your home was from the Daiichi plant (within 20 km or 30 km radius), how severe your location was affected by the radiation leak, and whether you were a forced evacuee (強制避難者) or voluntary evacuee (自主避難者).

Forced evacuees lived near the Daiichi plant within the 20 km or 30 km radius. People who were beyond this distance such as in Iwaki and northern and central Fukushima could evacuate as voluntary evacuees.

Forced evacuees have received free housing plus up to a total ¥14.5 million per adult just for mental anguish until July 2016. They could also receive compensation for their lost land and home. Some evacuee families of four have received as much as a total of ¥100 million in compensation.

Those who received the highest compensation had homes nearest to the Daiichi plant within the still-restricted zones mostly in Futaba, Okuma, and Namie Towns.

Meanwhile, voluntary evacuees, numbering around 1,500 in March 2020, received a paltry sum and only a limited period of free or low-rent housing until March 2019. These voluntary evacuees faced major problems and disruptions at the end of their temporary public housing contracts when they had to move out.

Compensation was also given for loss of income, property loss, evacuation expenses, home repairs, etc., etc. Most had statute of limitations which have passed.

Restricted zones remain

As of November 2023, the restricted zones were mainly in Okuma (60 percent restricted), Namie, and Futaba Towns (85 percent restricted). These towns still include small habitable areas centering on the main train stations. The restricted zones reflect the radiation plume that blew over the affected areas from the Daiichi plant.

As of February 1, 2025, Fukushima Prefecture’s evacuee count had decreased to 24,644 from the peak of 164,865 in May 2012. The number of evacuees is decreasing each year. Some 4,966 evacuees have stayed within Fukushima Prefecture, while 19,673 have evacuated outside the prefecture such as to neighboring Ibaraki (2,260), Tokyo (2,150), and Saitama Prefectures (2,119).

Radiation levels in the immediate area surrounding the Daiichi plant is still relatively high, but it’s off limits to the public.

The 3.11 disaster greatly affected tourism across board in Japan. In 2010, Fukushima Prefecture saw 57.17 million tourists. This shrank to 35.21 million in 2011.

In 2023, the number recovered to 53.923 million, a 13.1 percent increase over 2022, but still lower than in 2010. Naka-dori sees the most tourists, followed by Aizu. Hama-dori is therefore the place to go if you don’t like crowds.

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (福島第一原子力発電所) is on the central Hama-dori coast traversing the border of Okuma and Futaba Towns. It has six nuclear reactors, Units 1 to 6, which started operating in the 1970s. Units 1 to 4 were one reactor group in Okuma, while the newer Units 5 and 6 were another reactor group in neighboring Futaba.

“Daiichi” (第一) means “No. 1” because there’s also “Daini” or “No. 2” called Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant in a different location in Naraha and Tomioka Towns south of Daiichi. Although people within 3 km of Daini were ordered to evacuate and those within 3 to 10 km were to shelter in place, the Daini plant’s four nuclear reactors successfully shutdown soon after 3.11.

On March 11, 2011, the Daiichi plant’s Units 1 to 3 were in operation and Units 4 to 6 were undergoing regular inspections. When the earthquake occurred at 2:46 pm, the nuclear reactors in Units 1 to 3 stopped operating automatically. The earthquake knocked out electrical power, but the backup diesel power generators in the basement kicked in to supply power to the cooling system.

However, about 50 minutes later, the tsunami breached the seawall and hit the power plant and flooded and disabled the diesel power generators. It also washed away or damaged electrical power equipment, water pumps, fuel tanks, and emergency batteries causing a Station Blackout.

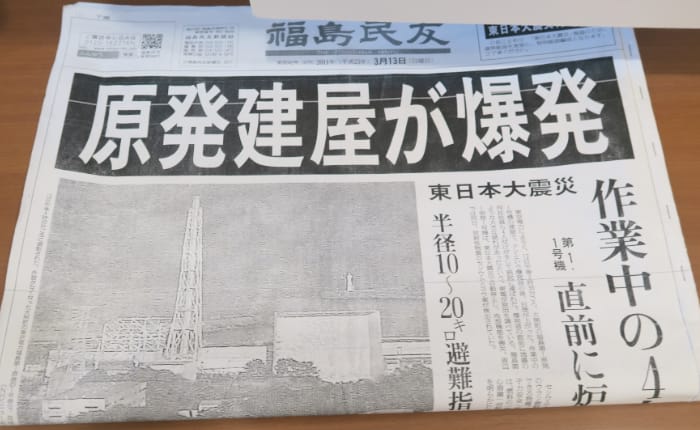

Without cooling water, the nuclear reactor and spent fuel pool could no longer be cooled, leading to partial meltdowns in Units 1 to 3 by the decay heat that continued even after the reactors were shut down. Due to the meltdowns, hydrogen gas accumulated and caused the reactor buildings for Units 1, 3, and 4 to explode on March 12, March 14, and March 15 respectively.

Although Unit 4 was not operating, it seems hydrogen from Unit 3 leaked to it and caused it to explode. The broken pipes, vapor leaks, coolant water leaks, etc., from the units released large amounts of radioactive substances into the air, water, and ground.

Meanwhile, Units 5 and 6 were on higher ground in Futaba Town away from Units 1 to 4 in Okuma. The tsunami inflicted less damage there. Fortunately, the backup diesel power generator for Unit 6 was on high ground and escaped tsunami damage. It was used to cool Units 5 and 6.

Units 1 to 4 were built on a cliff only 10 meters above sea level, while Units 5 and 6 were built 13 meters above the ocean. The Daini plant in Naraha and Tomioka was 12 meters above sea level. The degree of tsunami plant damage directly reflected the ground height of the power plants.

The cold shutdown of the Daiichi plant was finally confirmed in December 2011. Both Daiichi and Daini plants are being decommissioned, a process to take over 40 years.

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant pre-construction history

By the early 1960s, Japan was well on track for high economic growth and industrial modernization. Although Naka-dori and Aizu in Fukushima Prefecture were progressing well, the Hama-dori region lagged behind.

Hama-dori from Tomioka Town to Hitachi in neighboring Ibaraki Prefecture was the site of the Joban coal mining area since the 1870s. Coal mining was winding down due to the energy transition to oil. (The area’s last coal mine closed in 1976.) The forestry industry in Hama-dori was also declining.

In the late 1950s, the prefectural government looked for new sources of energy and surveyed the feasibility of building nuclear power plants in the prefecture. It found that most of Fukushima’s coast was suitable for a nuclear power plant and shortlisted Okuma, Futaba, and Namie Towns as prime sites.

At almost the same time, TEPCO also wanted to start nuclear power generation and had been looking at candidate sites for its first nuclear power plant.

In May 1960, Fukushima Prefecture officially invited proposals to build a nuclear power plant in the prefecture. It first approached Tohoku Electric Power Company which was not interested since it had just built the Okutadami Dam hydroelectric power plant in Fukushima and had a glut of electricity.

The prefecture started negotiations with TEPCO in September 1961. After examining more surveys, TEPCO agreed in 1963 to build the plant in Okuma and started purchasing the land in 1964. The location was favored as being relatively remote, away from heavily populated areas. Just in case there was a nuclear accident and any radiation leakage.

Both the Futaba and Okuma town assemblies unanimously voted to bring the plant to their towns following intense lobbying by TEPCO.

Plant construction and operation until 3.11

In 1967, construction of Unit 1 started in Okuma and operations started in 1971. Units 2, 3, and 4 were also constructed one at a time and respectively went online in 1974, 1976, and 1978 in Okuma. Units 5 and 6 were also constructed in neighboring Futaba Town and went online in 1978 and 1979 respectively. (Construction of Units 7 and 8 was also planned, but cancelled after 3.11.)

The Daini nuclear power plant’s Units 1 to 4 in Tomioka and Naraha Towns went online between 1982 and 1987.

This street sign was installed in front of JR Futaba Station in 1991 and removed in 2016 due to rust and age.

The Daiichi and Daini nuclear power plants brought major employment to the region and saved the local economy in the wake of coal mine closings and the rapid decline of farming and depopulation. It was also a period when power consumption grew in the Tokyo area. Things were going well for 40 years until March 11, 2011.

Although the nuclear power plants had an anti-tsunami seawall or breakwater in front, it was only 5.7 meters high. Tsunami waves as high as 15 to 20 meters easily went over the seawall and went as far as 500 meters inland around the power plant. Water as high as 4 or 5 meters flooded the exterior of all six nuclear reactor buildings.

The tsunami also went over the Daini plant’s seawall and flooded the southern side of Unit 1.

Nobody held legally responsible

Despite all the trouble, panic, evacuee deaths, extinction of communities, loss of livelihoods, and enormous monetary cost the ill-equipped nuclear power plants have caused, the TEPCO (Tokyo Electric Power Company) executives in charge at the time have all been acquitted on negligence by Japan’s Supreme Court on March 6, 2025.

The Court stated that such a giant tsunami hitting the plant was unforeseeable even though the prosecution side claimed that TEPCO could have prevented the disaster if it had listened to experts and installed adequate safety measures. Incredibly enough, no one has taken criminal responsibility for the nuclear disaster and meltdowns.

Decommissioning the reactors

However, TEPCO continues to remain liable to provide compensation to victims, ensuring the safety of nuclear reactors, and decommissioning the reactors which will take at least 40 years. (They are already behind schedule by a few years due to mistaken procedures or faulty equipment.) The nuclear reactors containing highly radioactive fuel debris are in a stable condition with injected water cooling the debris.

Fuel debris is the nuclear fuel that melted and mixed with structural materials and later solidified upon cooling. It’s a highly radioactive material harmful to humans and only robots can be used to remove it. In October 2024, TEPCO successfully removed a tiny sample of fuel debris from Daiichi’s Unit No. 2.

They are spending months to examine the composition and condition of the fuel debris sample to figure out how to proceed with the full scale removal of 880 tons of fuel debris from the three reactors. They still need to remove more samples from various locations since their composition will vary.

The 3.11 disaster was a major setback for Japan’s nuclear power industry. Before 3.11, nuclear power accounted for up to 30 percent of Japan’s electrical power generation. As of 2023, it accounts for only about 5.55 percent generated by 14 nuclear reactors. Some 27 nuclear reactors have been shutdown permanently including all of TEPCO’s nuclear reactors.

Although Japan initially pledged to depend less on nuclear power following 3.11, it has recently announced a policy to focus more on nuclear power since the demand for electricity has been increasing.

Decontamination work

Right: Flexible container bag has 1.1 meter diameter with a capacity of 1.0 cubic meter and max. weight of 2 tons. Made in India.

Fukushima’s decontamination and cleanup work involves the removal of contaminated topsoil and burnable waste (tree branches, brush, etc.) which is incinerated. The topsoil and incineration ash are stored separately. One thing you see in Hama-dori are many power shovels.

The topsoil and burnable waste are first put in large, black bags (called “flexible container bags”) and stored on-site or at temporary storage sites.

Then they are sorted and processed or incinerated and the soil and incineration ash are stored at the Interim Storage Facility (ISF 中間貯蔵施設) around the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant site in Okuma and Futaba Towns. The ISF was setup in March 2015, and the bagged soil and waste started to be brought there from many scattered locations.

The ISF occupies 1,600 hectares or 14 percent of Okuma’s land area and 10 percent of Futaba’s land area. It’s the same area as Shibuya Ward in Tokyo with 16 sq. km or 6.1 sq. miles. As of Feb. 2025, 14.07 million cubic meters of contaminated topsoil and ash have been stored, enough to fill Tokyo Dome 11 times.

By law, the Japanese government promised Okuma and Futaba Towns and Fukushima Prefecture that the stored contaminated topsoil and debris will be moved to a final storage site outside Fukushima Prefecture by March 2045 or 30 years after being stored in Okuma and Futaba since 2015. This is to lessen the nuclear burden on Fukushima.

That’s only 20 years from now, and the final storage site has not yet been decided. From the latter 2020s, there are plans to reuse the less contaminated soil for foundations under roads and other public works nationwide. Soil with higher levels of radiation will be stored permanently somewhere outside Fukushima.

However, all the proposed storage sites on public lands outside Fukushima Prefecture have faced fierce local opposition. The Japanese government still has to obtain the understanding of the Japanese public and aims to come up with a permanent storage plan within this decade. The negative stigma of radiation remains strong, even though sugar, fat, alcohol, cigarettes, and car accidents kill many more people.

“Hope tourism” in Tohoku Region

The Pacific coast of Tohoku which includes Fukushima, Miyagi, Iwate, and Aomori Prefectures now has many memorial museums, monuments, preserved tsunami-damaged schools and buildings (disaster heritage sites), and other testaments of the triple disaster.

The region has established a network of all these facilities and monuments called “3.11 Densho Road” (3.11伝承ロード). Their website lists all the 3.11 museums and memorials. They want to disseminate their triple disaster stories and the lessons learned to current and future generations to spread the importance of disaster preparedness. The ultimate objective is to save more lives in future natural and manmade disasters by being better informed and prepared.

Memorial museums are being called denshokan (伝承館), literally meaning “dissemination museum.” One common feature of these museums are local people (called kataribe 語り部) who personally experienced the disaster sharing their stories. They don’t want their stories to be forgotten. It’s very worthwhile and interesting to hear their stories.

In Fukushima, the largest memorial museum is the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum in Futaba Town. There’s also the Soma City Memorial Hall in Soma.

Fukushima densho: https://www.densho-road-fukushima.com/en/

Tohoku densho: https://www.311densho.or.jp/en/

Map of 3.11 museums and memorial sites: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=15huBn896DdthDv1_sWA-4Whc2fYUKqWD&usp=sharing

Also see:

- Fukushima’s Road to Recovery (top)

- Fukushima’s three regions

- March 11, 2011 triple disaster in Fukushima

- Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant

- “Hope tourism” in Tohoku Region