Akebono Tribute Contents

- Azumazeki Stable (Current page)

- Ozeki Promotion

- Yokozuna Promotion

- Retirement Ceremony

Visited Azumazeki-beya Stable in August 1991 while Akebono was still a maegashira. Also had a casual interview with Akebono over lunch. *This article first published in 1991, updated in May 2023.

A group of us from Hawaii visited Azumazeki Stable (東関部屋) in May and August 1991. Azumazeki is of course the sumo elder (toshiyori) name of former Takamiyama (高見山), alias Jesse Kuhaulua from Maui, Hawaii.

Azumazeki oyakata opened his own sumo stable in April 1986, two years after he retired from the sumo ring at age 39. For a foreigner like Jesse, becoming a sumo elder to pave the way to open a sumo stable had its obstacles. In 1976, the Japan Sumo Association suddenly made Japanese citizenship a requirement for retiring sekitori (a sumo wrestler in the top two divisions of Makunouchi and Juryo) to purchase toshiyori kabu (sumo elder stock 年寄株).

In order for a sekitori to remain in the sumo association after retirement, he must own one of the 105 toshiyori stocks. This stock is purchased from a sumo elder who dies or reaches the mandatory retirement age of 65. Each stock bears a sumo elder name and the one Jesse owns is named “Azumazeki.”

When you own toshiyori kabu, you can remain in the sumo association and work in various positions such as a ringside judge. You can also open your own sumo stable if you have the money and resources. Since Jesse did not want to leave sumo, he reluctantly gave up his U.S. citizenship to become a Japanese citizen in 1980. This made him eligible to make arrangements to purchase toshiyori stock while still an active wrestler.

Sumo elder stocks are expensive (rumored to exceed ¥100 million as of 1991) and these days more difficult to obtain since their owners are living longer. Therefore, sekitori usually make advance arrangements to purchase a stock while still active in the ring.

Azumazeki Beya is located in Tokyo’s Sumida Ward near Honjo Azumabashi Station on the Toei Asakusa subway line. The stable is a convenient mile and a half from the Kokugikan (National Sumo Arena 国技館) in Ryogoku. It is the first sumo stable opened by a foreign-born stable master.

From the outside, the stable looks like any other building on the block. It is a modern, four-story, ferro-concrete structure. You know it is a sumo stable by seeing the “Azumazeki Beya” wooden sign at the entrance. It is also home to Azumazeki oyakata and his family (on the top floors) and around ten sumotori (sumo wrestlers, also called rikishi 力士). (As of 1991.)

The keikoba (sumo practice area 稽古場) faces the street on the ground floor. We saw it immediately as we entered the building. After taking off our shoes at the genkan entrance hall, we entered the keikoba. We were on the agari-zashiki (上り座敷), a raised, varnished-wood platform fronting about half the practice area’s perimeter. This was where visitors (as well as the stablemaster) would sit on zabuton cushions to watch the sumo practice.

On the right corner above the agari-zashiki was a small Shinto altar. At the right rear corner of the practice area, there was the teppo, a wooden pole stuck vertically in the ground for wrestlers to slap their hands on. The wall facing the street had large barred windows, a towel rack, and a row of slats on the bottom for ventilation. The ceiling had four wood-panel sides, with recessed lights, converging upward toward a point in the middle. The whole place was quite modern and uplifting.

The left wall had small wooden tags with the ring names (shikona 四股名) of the stable’s sumotori. They were arranged according to sumo rank. Usually, the ring name is based on the stablemaster’s former ring name. At first, most of the stable’s wrestlers were named Takami-something after stablemaster Takamiyama. But later on that custom was discontinued.

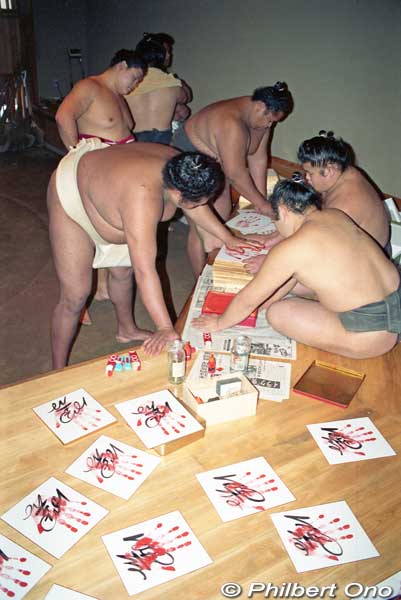

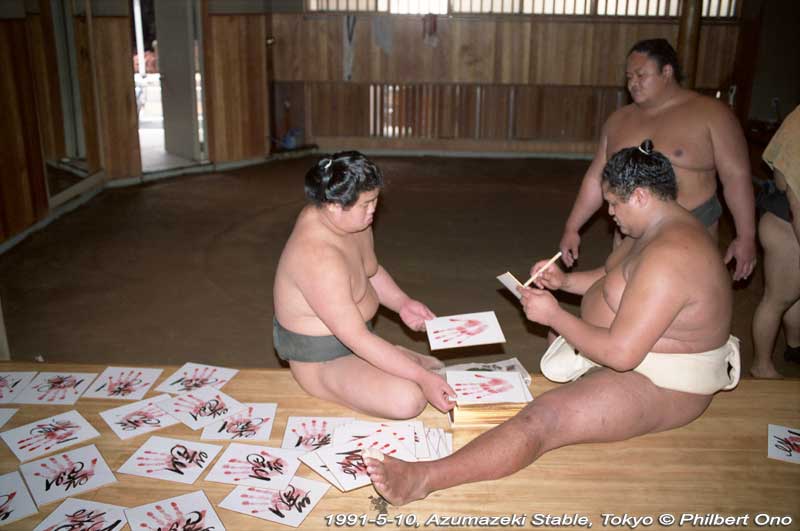

On our first visit in May 1991, we arrived at around 10 a.m. The wrestlers had just finished practice. They finished early because the stablemaster was away. The underling wrestlers were sweeping the ring and tidying up the place. “New Dawn” Akebono (Chad Rowan) was also there and soon started to make those tegata (handprints 手形) on a stack of square cardboard placards. Assisted by his tsukebito (personal attendants 付人), Akebono patted his left hand once on the large flat sponge moisten with red ink and slapped the top placard. The tsukebito then removed the stamped placard and Akebono re-inked his hand and slapped the next placard on the stack. This was done in rapid succession.

I counted at least a few large tubes of vermillion ink consumed in the process. The dried tegata were restacked and given to Chad for him to autograph with a calligraphy brush. It took only a few seconds for him to sign one, after which he tossed it frisbee-style on the agari-zashiki which was soon covered with the tegata. Afterward, we had an enjoyable lunch with two of Akebono’s tsukebito who were from Hawaii.

Since we missed seeing the sumo practice on our first visit in May 1991, we made a second visit in late August 1991. We entered the stable at around 10 a.m. and could hear the panting, grunting and body slaps of the wrestlers. Azumazeki oyakata (stablemaster and former Takamiyama) was sitting on the agari-shiki and watching the practice. His wife, the okami-san, was also watching while standing at the entrance of the practice area (keikoba).

When the stablemaster watches the practice, the atmosphere of the place changes. Everyone does his best to impress him. Akebono was in full force, clashing with his large stablemates from Hawaii. Everyone was covered with sweat-mixed dirt. Since Akebono was the heya-gashira (highest-ranking wrestler in the stable), he was the boss and directed the practice. We saw their butsukari-geiko (collision practice) where Ozora (also from Hawaii) kept charging at Takeru and pushing him around the practice ring. He did this repeatedly until he was thrown to the dirt.

“Hit the chest!” “Hit the middle” barked Akebono at Ozora. “Run through him, not over him!” This was one notable feature: the use of (pidgin) English. I wondered how much of the English was rubbing off on the Japanese stablemates. Every once in a while, one of the younger wrestlers would offer a ladle of water to Akebono and the stablemaster. It was spellbinding to watch these huge people work out until they looked like they would pass out.

The oyakata said little during the practice. He was wearing an aqua Maui Bay T-shirt and spoke to us in English. When I told him I was originally from Maui, he lit up. Always nice to meet another Maui boy. He once told the press that in his stable, he emphasized the “go for broke” fighting spirit rather than sumo technique. You may see him sitting ringside during tournaments since he was recently made a ringside judge.

The practice was capped by a series of exercises including shiko sumo stomping and matawari sumo splits. All the while, they shouted out numbers like, “Ichi-ni-san! ichi-ni-san!” or “Ichi-ni! ichi-ni!” Finally, they all fell silent and squatted as Akebono said, “Mune wo hatte, ago wo hiite!” (Chests out and chins down!) and called to Ozora who led the nine other wrestlers through the three points of the sumo code of honor (“I will respect my elders,” etc.). Then they stood up (senior wrestlers first), clapped twice, and ended with “Domo osewa ni narimashita” (Thank you very much for your help).

Akebono and the others took a bath and came out in loose-fitting clothing. Then they got their hair done by the stable’s hairdresser. We asked Ozora (Troy Levi Talaimatai) who was from Honolulu to have lunch with us and Akebono joined us.

As we walked to the restaurant, friendly Akebono called on his neighbors (the corner dry cleaners and the local tailor) on the spur of the moment. He just chatted with them for a while. He was obviously well liked by those who knew him personally. The neighborhood photo shop even had an autographed (in English) picture of him prominently displayed above the sales counter. He was being a great goodwill ambassador.

Akebono is the pride of Azumazeki Stable. Within four years of its establishment, it produced a sekitori (sumo wrestler in the top two divisions of Makunouchi and Juryo) in Akebono. This is quite an achievement considering that it usually takes five or more years to do so.

Born in May 1969, Akebono made his sumo debut in March 1988 and made it to the top Makunouchi Division in September 1990. He was once ranked as high as Sekiwake, the doorstep to the coveted Ozeki rank. He hails from Waimanalo on the island of Oahu and attended Kaiser High School. He is 204 cm (6’8″) tall and weighs 193 kg (428 lb).

Greatly contributing to his rapid rise in sumo was his 18 consecutive kachi-koshi (majority of wins) sumo tournaments, breaking former Ozeki Takanohana’s record. However, after making it to Sekiwake, he failed to get at least 8 wins in two tournaments and was demoted to Komusubi and later down to the upper Maegashira ranks. Hopefully he will climb back up soon.

We (seven of us) arrived at the restaurant and sat at the counter. Ozora sat on one end and Akebono sat on the other end. We ordered shabu-shabu with thin, marbled slices of delicious Yamagata beef. Akebono didn’t order anything for himself. He said that if you feel hungry after practice, it means you didn’t practice hard enough. (Ozora, however, helped himself.)

I don’t know if that applied to only that day or all the time. He kept joking with the jovial middle-aged ladies serving us, one who even slapped his massive thigh and said, “What big thighs you have, Bono-chan!” Akebono’s Japanese is very good, perhaps better than his standard English. The young women customers in the restaurant were amazed at the size of Akebono and Ozora.

I sat next to Chad (we called both of them by their real first names) and we got to talk. Knowing that we were from Hawaii, he spoke very heavy Hawaiian pidgin English. He was also down-to-earth and easy to talk to despite his daunting size.

His pidgin English is also apparent when he speaks to his stablemates from Hawaii. He calls them by their real first names in informal conversations and sometimes bosses them around in English. “Get my wallet” or “Get my T-shirt.” Troy (Ozora) does it without question. Of course, no one likes being bossed around or being a servant to another. This is a built-in incentive for them to escape such a life by climbing up the sumo ranks.

It was late August 1991 and Akebono and all the other Makunouchi wrestlers had just completed a one-month exhibition tour (jungyo) of the Tohoku Region after the Nagoya tournament in July. Chad mentioned how tiring the jungyo was. “It was riding on trains or buses for long hours almost daily. But it was good for the tsukebito (personal attendants) who had to carry all the luggage around, to build up their strength.”

Azumazeki oyakata was the chief coordinator of the summer jungyo and had to take care of trivial details (which are the most important) such as the size of the toilet and bath of the private homes where the upper-ranked wrestlers were to stay.

A TV special on the summer jungyo focused mainly on Akebono and the Hanada brothers. Akebono is given much attention in the press and always grouped with the Hanadas as being one of the most promising young sekitori. One scene showed Akebono staying at a private home in rural Akita Prefecture. The hosts selected the best rice, the best home-grown vegetables, and the local specialties for him. Akebono was always cracking jokes. The male host asked him if he knew about Akita Bijin (Akita Beauties 秋田美人). Akebono then pointed to the old ladies (the host’s wife, etc.) in the house and said, “Akita Bijin.”

Chad is basking in his celebrity status, even in Hawaii. When he visited Hawaii in February 1991, there were two police officers who addressed him as “Mr. Rowan” and escorted him from his plane. (He smiled and raised his eyebrows as he told me this.) He mentioned how popular sumo has become in Japan and Hawaii.

So I told him, “Hey, you’re really famous now!” But he modestly brushed it off and said that he’s still not “big time.” “Big time” must have meant being an Ozeki or above. When I said, “You have to make it to at least Ozeki,” he quickly affirmed, “Yeah, at least Ozeki.” (Heavy emphasis on the “at least.”)

I asked how he supposed to learn all those belt throws and other sumo techniques. “You learn it by being thrown around during practice. After being thrown, you try to figure out what technique was used for that throw.” Mastering sumo seemed to be more of a trial-and-error process than the structured course of learning karate or judo.

Since Akebono is the only sekitori in the stable, he needs more stimulation than just practicing with his non-sekitori stablemates. Therefore, he goes out to other stables to practice (de-keiko 出稽古). Takasago Beya, which is Takamiyama’s former stable, is where Ozeki Konishiki is.

I asked Chad how often he goes to practice at Takasago Stable. “Whenever I feel like it,” was his answer. When Akebono practices with Konishiki, they speak English on the practice ring. It makes some observers feel that sumo is becoming really international.

Konishiki, alias Salevaa Atisanoe, is of course the other foreign wrestler in the Makunouchi division and Takamiyama’s successor. Or should I say one of the other two foreign Makunouchi sekitori now that Musashimaru (of Musashigawa Stable and also from Hawaii) has entered the top division in November 1991.

Seeing one foreign sekitori is a thrill, and having three is really a triple thrill. And they all happen to be from Hawaii. At first, it was sad to see two foreigners pitted against each other. I couldn’t decide who to root for. But now, it adds to the excitement.

Chad talked about Konishiki as a rival and someone to beat. He had this determined look on his face as we talked about Konishiki. Forget that Konishiki taught him a lot or that he helped him train. And forget that they are good friends off the ring. On the ring, no holds barred. Both fight to win. And Akebono has already demonstrated that he can beat Konishiki.

One challenge which Akebono missed was a match with Chiyonofuji since the latter retired. “I wanted to fight him, but not when he was past his prime. Only if he was in his prime…” It was talk like this which really struck me. You can definitely sense his strong will and determination.

Another disadvantage of being the only sekitori in the stable is that there is no one in the stable to take a vacation with. After each tournament, there is usually a week’s vacation when a sekitori can do whatever he wants. “I want to travel to many places like Jamaica…”

But he hesitates to go alone since it would be too noticeable and overbearing. In a small group, it would be no problem. Therefore, he really wants Ozora to come up to at least Juryo to have a traveling companion. It has been over two years since Ozora entered sumo and he is still in the Makushita Division (right below Juryo). Chad says that Troy should have made it to Juryo in two years like he did. (Ozora never made it beyond Makushita and eventually retired.)

Another complaint of his concerned some of the overseas press people who ask him dumb questions like “How do you get so fat?” or “Do you like sumo?” etc. He says these press people are so ignorant of sumo. “But not the local English press in Japan, right?” I quickly tried to confirm, being a magazine reporter. “Oh no, not them,” he replied to my relief.

He asked us if we wanted any more meat or food. We said no. We had planned to treat him and Ozora to lunch, but ended up being treated instead. It was nice talking to Akebono and hearing his funny stories. It was a far cry from his demure Japanese responses to television interviewers. We shook hands outside on the sidewalk and said goodbye as they walked back to their stable.

May 2023 update: After Jesse retired in June 2009 at age 65, Azumazeki Stable was taken over by Ushiomaru who moved the stable to Shibamata, Katsushika Ward in Tokyo in Feb. 2018. However, Ushiomaru died in Dec. 2019 at age 41. Former wrestler Takamisakari temporarily took over Azumazeki Stable for a year from January 2020. However, he did not want to be the permanent successor. With no Azumazeki successor, Azumazeki Stable was shut down after the March 2021 tournament with the wrestlers and staff moving to Hakkaku Stable headed by the current Japan Sumo Association chairman. Meanwhile, the original sumo stable building built by Jesse aka Takamiyama has been occupied by Miyagino Stable since Aug. 2022 headed by former Yokozuna Hakuho.

Next page here (Ozeki Promotion)…

Akebono Tribute Contents

- Azumazeki Stable (Current page)

- Ozeki Promotion

- Yokozuna Promotion

- Retirement Ceremony