日本の美しい苗字(名字)の画像化、60選!

by Philbert Ono, updated: Dec. 19, 2023

Most of us don’t usually think about it, but many Japanese family names contain beautiful imagery reflecting Japan’s natural beauty, rural scenery, agrarian society and history, traditions, and the legacy of aristocratic and samurai clans.

To give you a visual idea of what’s in Japanese surnames (myoji 名字 or 苗字), I’ve created (prompted) about 60 images illustrating common Japanese family names like Tanaka, Sato, Suzuki, Yamamoto, Nakamura, Fujiwara, Ohtani, Matsuno, and even a few Okinawan surnames. Images were made possible with a free AI (Artificial Intelligence) image generator. (It would be very difficult to create most of these images photographically with a camera or Photoshop.)

After reading this post, you might never view these Japanese family names in the same way again. These sample images only come from my informed imagination and may or may not reflect the name’s actual origin or meaning. Usually there are multiple origins and meanings.

Although common Japanese people didn’t have official family names until 1875 when family names were required by law, many of them gave themselves an unofficial or casual surname from the Heian or Kamakura Periods (late 12th to 14th centuries). Since the family names were unofficial and there were no laws for names, people could freely name themselves or change their surnames.

If everyone living in the same village named themselves after the village or had the same surname, it would make it harder to identify each other. People and branch families therefore freely changed or modified their family names to better distinguish themselves. Only the nobility and samurai had official family (clan) names.

When everyone in Japan was required to register a family name in 1875, most people officially named themselves after a local place name (hometown), the name of their village, a natural or man-made feature, the name of the local ruling clan, or their occupation.

Much research has been done on Japanese names, but much is still a mystery since many names are so old. Although many Japanese family names can be traced to some clan/family or place name, it is harder to find out what inspired the name. This is what I need to know to more accurately create visuals of Japanese family names. Most names have more than one possibility concerning its origin. I’ve tried to choose the most prominent one.

Many names have agrarian roots, natural scenery, cardinal directions, or aristocratic origins. Japanese family names are a window into another aspect of Japan. Out of Japan’s estimated 200,000+ family names, about 60 of them are illustrated below. (Click on the image to enlarge.)

Alphabetical index: Akiyama | Aoki | Enari | Fujii | Fujita | Fujiwara | Hayashi | Higa | Hirano | Hoshino | Ikeda | Inoue/Inouye | Ishii | Ishikawa | Ito | Kato | Kikuchi | Kimura | Kojima | Matsudaira | Matsui | Matsuno | Matsushima | Matsuyama | Miho | Miyashiro/Miyagi | Murakami | Nakajima | Nakamura | Nishimura | Nitta | Nomura | Ogawa | Ohtani | Okada | Ono | Oshiro | Sakurai | Sato | Shigeta | Shimabukuro | Shimada | Shimamura | Shimizu | Suzuki | Takahashi | Takayama | Tamaki/Tamashiro | Tanaka | Toyama | Toyoda | Tsuchida | Tsukiyama | Tsuruta | Uchida | Watanabe | Yamada | Yamaguchi | Yamamoto | Yamashita | Yoshida

All images prompted by Philbert Ono.

Tanaka (田中): This is one of the top five common names in Japan. It also epitomizes Japan’s numerous rice paddy family names containing the word “ta” or “da” which means “rice paddy.” The kanji character is a simple square divided into four smaller squares (田). It’s a pictograph of square rice paddies as seen from above like this image (with a farmer in the middle).

We can assume that people who chose a rice paddy name were rice farmers. Rice was used to pay taxes to the samurai government, so it was a universal occupation. The large number of rice paddy family names reflect Japan’s dominant agrarian society in the past.

Yamada (山田): Japan being mostly covered by mountains, many people had to grow rice on a mountain. The most practical method was to carve out terraces on the slopes. People who created terraced rice paddies called it “Yamada.” And the people who lived nearby named themselves “Yamada.”

Yamada is also widely considered to be the most typical Japanese surname as in “Yamada Taro” for males and “Yamada Hanako” for females. The kanji characters for “yama” and “da” are among the most basic in Japanese and denote two of the most essential things in Japan. The name was also popularized by manga, anime, and a popular singer named Yamada Taro in the 1960s.

All three syllables in Ya-ma-da also has the “a” vowel sound, making it easy to pronounce and hear. The “a” vowel makes the mouth open the widest.

Requiring intensive work, terraced rice paddies are now rare in Japan. Those which still exist are beautiful and impressive tourist attractions. Yamada is similar to “Sakata” (坂田) which is “Sloping Rice Paddies.”

Tsuruta (鶴田): The beloved crane is an auspicious symbol of longevity, good fortune, and loyalty. They indeed can be seen feeding in rice paddies especially in winter.

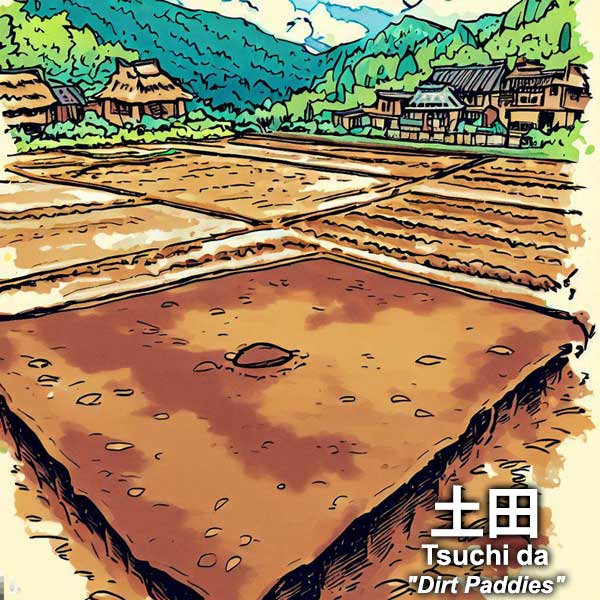

Tsuchida (土田): This might be a new rice paddy or one being prepared for planting.

Nitta (新田): Land that was recently cleared to make new rice paddies. Common name in Okinawa. Can also be pronounced “Arata.”

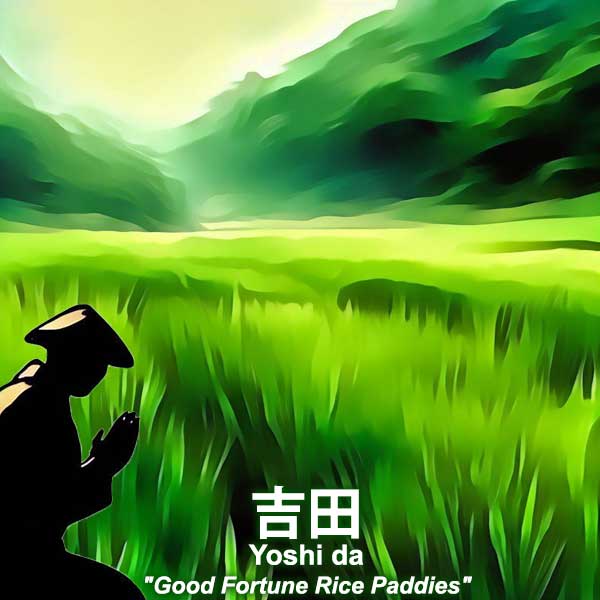

Yoshida (吉田): Very common name with “Yoshi” found in many Japanese family names and place names since it means “good fortune.” “Yoshida” has the nuance of the person praying or hoping for the rice paddy to bear a good harvest. Might be religious, but farming in Japan has always been associated with local religion.

Shigeta (重田): “Shigeta” can be written in multiple ways (like 茂田 and 繁田), but they all basically mean the same. “Heavy” refers to the plants being heavy with a lot of rice grains to reap an abundant harvest.

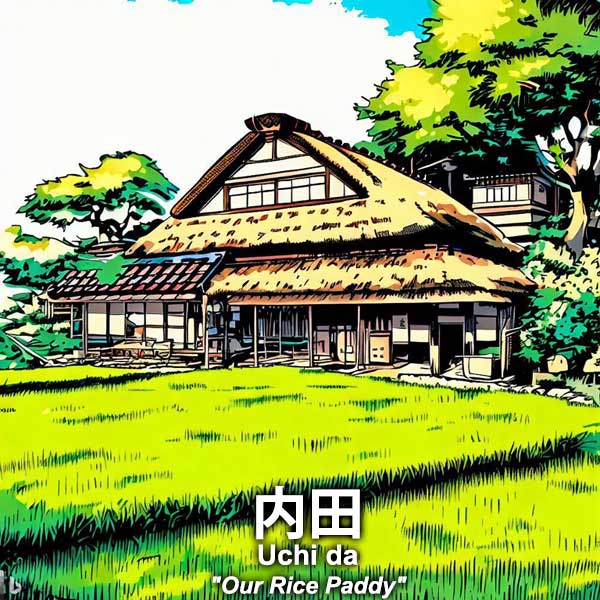

Uchida (内田): Meaning “inside” or “inner,” “uchi” can have multiple meanings. It could be your own rice paddy in your backyard, or a paddy within the village.

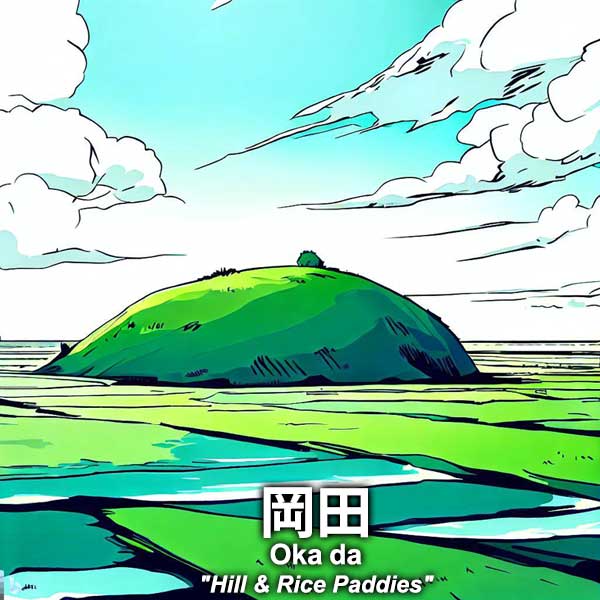

Okada (岡田): “Oka” means “hill.” Not sure if it means a hill amid rice paddies or a hilltop rice paddy. The former is more plausible though. It’s not practical to grow rice on a hilltop amid a flatter area.

Ikeda (池田): “Ike” is pond. Rice paddies supplied with water from a nearby pond.

Fujita (藤田): “Fuji” here means wisteria. Being a beloved flower, “fuji” appears in many Japanese family names like Fujii, Fujitani, Fujioka, and Fujimura. It might also be related to the Fujiwara Clan.

Not to be confused with Mt. Fuji which is written differently and has a different meaning.

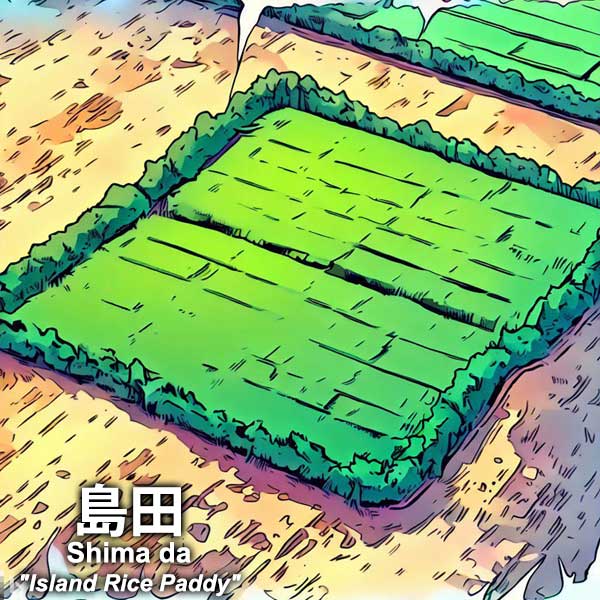

Shimada (島田): Although “shima” means “island,” it could also refer to a district or area set apart from the rest. Rather than being an island of rice paddies, Shimada was likely a rice paddy in a location separate from other paddies.

Toyoda (豊田): “Toyo” has a strong connotation with “abundant harvests” since the word for it includes “toyo” as in hosaku (豊作). Toyota Motor was founded by Kiichiro Toyoda. His ancestor was indeed a farmer (in Shizuoka).

Miho (三保): “Miho” is not a common family name, but well known as a place name and tourist attraction in Shizuoka Prefecture (Miho-no-Matsubara 三保松原).

As a family name, it’s difficult to figure out because it has no distinct meaning or imagery. We need more context to figure out what it means. Some Japanese family names are like this.

Many Miho families originated in Niho (仁保) in Hiroshima where a man named Miho Ihei (三保 伊平) bought and sold seaweed in that area and became very prosperous in the late 19th century. But how and why was his family named “Miho”?

Many Japanese family names can be traced to a clan, family, or place name, but it’s harder to pinpoint why those families/clans/places got that name unless it’s self explanatory such as a rice paddy name or natural feature.

Adding to the confusion is the tendency for people to change their names or the kanji characters for their name while retaining the same pronunciation. Name researchers can only theorize.

In the case of the Miho-no-Matsubara place name in Shizuoka, it refers to a slender peninsula of pine trees with a view of Mt. Fuji made famous by Hokusai’s ukiyoe print. There are multiple theories on the origin of the kanji characters. They might have been 美穂 (beautiful ears of rice) or 三穂 (three ears of rice) or 御保 (protection) or 美秀 (outstanding beauty), all pronounced “Miho.” Then it was changed or popularized as 三保 used today. It literally means three protectors or preservers (of something).

The area originally had three thin peninsulas bending toward shore like a ripe rice plant (this image). It might have inspired the Miho place name somehow. But I haven’t yet found out how the Miho (三保) surname came about.

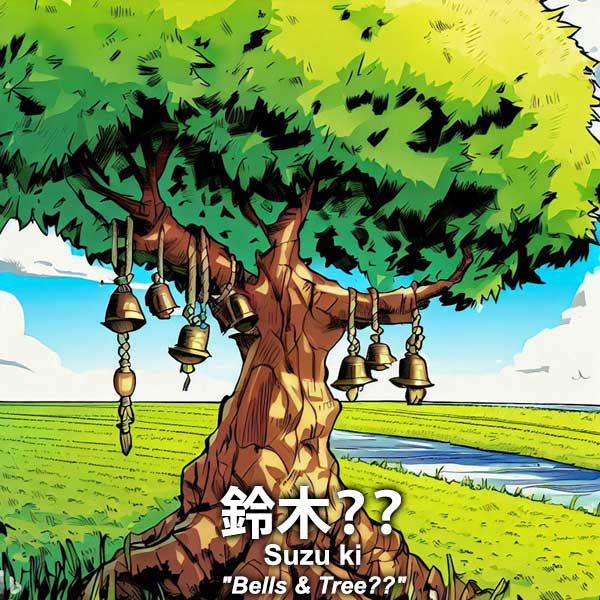

Suzuki (鈴木): “Suzuki” is Japan’s No. 2 most common family name, right behind “Sato.” The name’s meaning is very puzzling because the meaning of the kanji characters does not make sense.

It literally means “Bell Tree.” But what the heck is that? A tree with bells?? At first, I could only think of the bell tree used in prayer dances for a good harvest. The real bell tree (photo below) is shaped like a ripe rice plant with ball-shaped bells being the ripe, golden grains of rice. However, this bell tree is not called “suzuki” in Japanese, just “suzu.”

If the literal meaning of a family name sounds silly or impossible, it’s probably not the correct meaning. Upon further research, I found out that “Suzuki” actually has a totally different meaning and there’s a long and interesting history (even myth) behind the name.

“Suzuki” turns out to be a rare case where the kanji characters are used only for phonetic purposes (ateji 当て字) and not for the meaning. In other words, the kanji characters for “Suzuki” don’t match the original meaning.

The word “suzuki” (スズキ) in this case comes from Wakayama Prefecture’s Kumano dialect meaning “piles of rice straw” (wara-zuka わら塚) made by farmers as a gesture of prayer to have the rice seeds blessed by the gods for an abundant harvest. The straw would also be used to make shimenawa sacred ropes to hang on the shrine’s torii. (To see actual photos of these rice straw stacks, search for わら塚.)

Since kanji characters were not invented for suzuki in the Kumano dialect, these phonetic kanji characters (meaning “bell tree”) were used.

*Blog post with more details about the Suzuki surname: https://photoguide.jp/log/2023/06/suzuki-surname-origin/

Hirano (平野): Besides rice paddy (“ta” or “da”), “no” (野) meaning “field” is also very common in Japanese family names. “Field” is usually dry farm land other than wet paddies.

This was an easy image to create (or prompt) although there’s usually mountains in the far distance. The kanji characters can also be pronounced as “heiya” which is a common Japanese word for “plains” or flatland.

Ono (小野): This “Ono” meaning “Small Field” is not to be confused with “Ohno” (大野) meaning “Big Field.” In English, both names are pronounced the same. In Japanese, the pronunciation is different with a long Ō sound for “Big Field.” Confusion can occur if Big Field is also spelled as “Ono.”

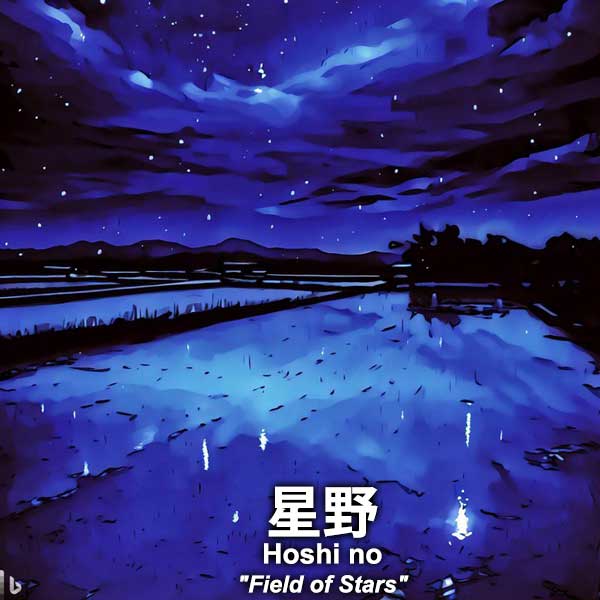

Hoshino (星野): For “field of stars,” I could only imagine a wet rice paddy reflecting the starry sky at night. Could not consider the sky as a field since it moves or flows like a heavenly river (which is what the Milky Way is called in Japanese). Made me realize how pretty the name “Hoshino” is. I wonder if a scene like this inspired the name.

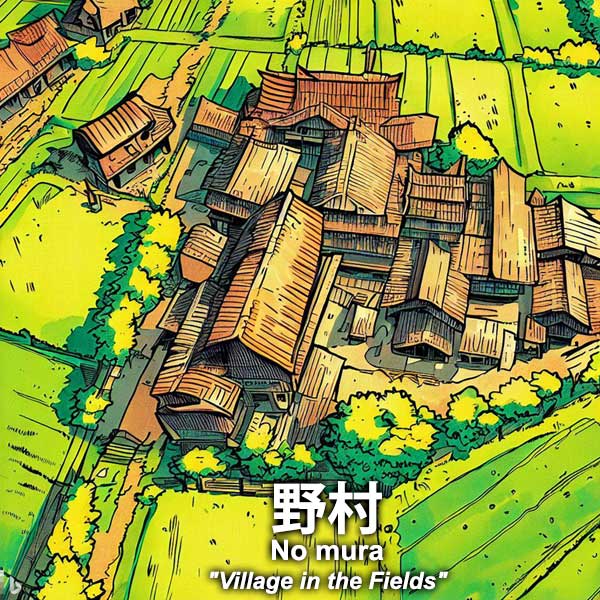

Nomura (野村): Another self-explanatory family name. Similar to “Noda” (野田) meaning Village in Rice Paddies. Both “No” (field) and “mura” (village) are common words in Japanese family names.

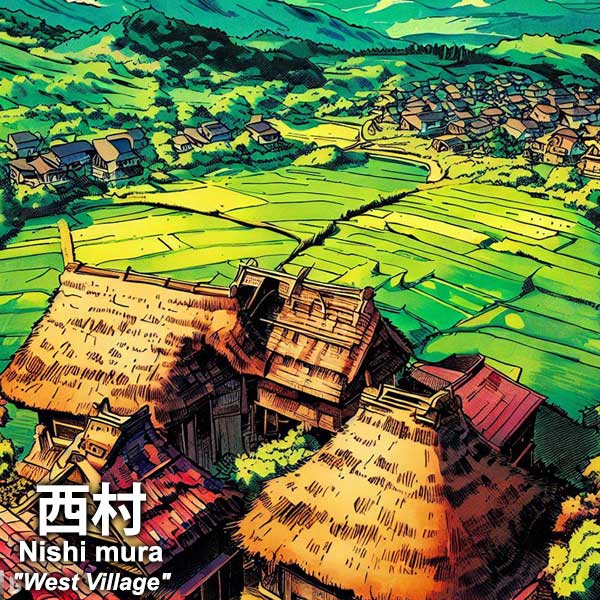

Nakamura (中村): “Mura” (village) is another common word in family names. “Nakamura” is perhaps the most common one since it means “middle” or “central” village. Nakamura was the main, original village, and when it got too big, the village split off into a branch village founded in the west (nishi) or north (kita). The branch village was named according to the direction with respect to the Nakamura village.

Nishimura (西村): “Nishimura” means West Village since it was a branch village founded in the west (nishi) of the Nakamura central village. Similarly, the branch village founded north (kita) of the central village became “Kitamura” (北村) or North Village. Many people named themselves after their respective farm villages.

Just because people had the same family name, it did not mean they were related by blood. We can assume families with a “mura” name were originally farmers similar to rice paddy families.

Cardinal directions are another common element in Japanese family names and especially place names. Many village, river, and mountain family names had cardinal directions like Kitagawa (North River), Nishikawa (West River), and Nishiyama (West Mountain).

However, “Higashi” (east) and “Minami” (south) are less common in family names (common in place names though). Why? Because people favored living in the north or west of the rice paddies or central village. The north and west locations received the most sunshine from the south and east. When common Japanese started giving themselves a family name during the late 12th to 14th centuries, most were living in north and west locations.

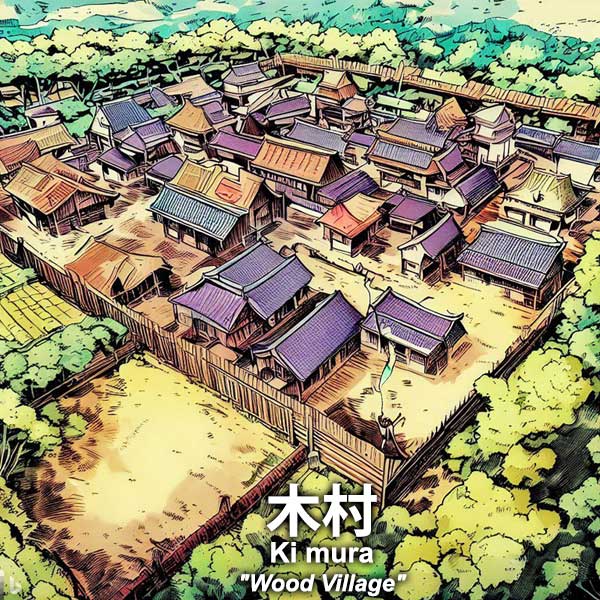

Kimura (木村): Another very common mura name. It may refer to a village with lots of trees or wood, implying that it is an old village compared to a new village that might be called “Niimura” (新村).

It may also have been a village enclosed by a wooden wall to distinguish itself from newer villages.

Although “Ki” means wood, it could have taken the name from Kii Province in present-day Wakayama Prefecture or from a place named “Kimura” in Higashi-Omi, Shiga Prefecture.

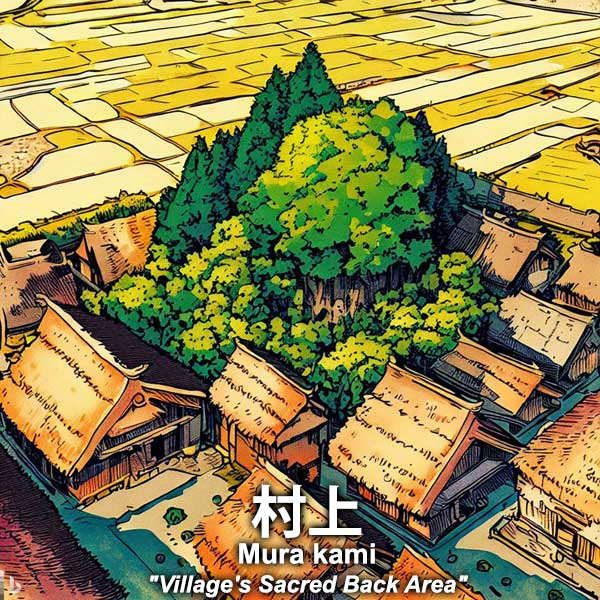

Murakami (村上): “Kami” can mean “god” or “above.” This might refer to the rear of the village where there was a small forest, the home of a local god. The rear of the village was usually on a higher elevation.

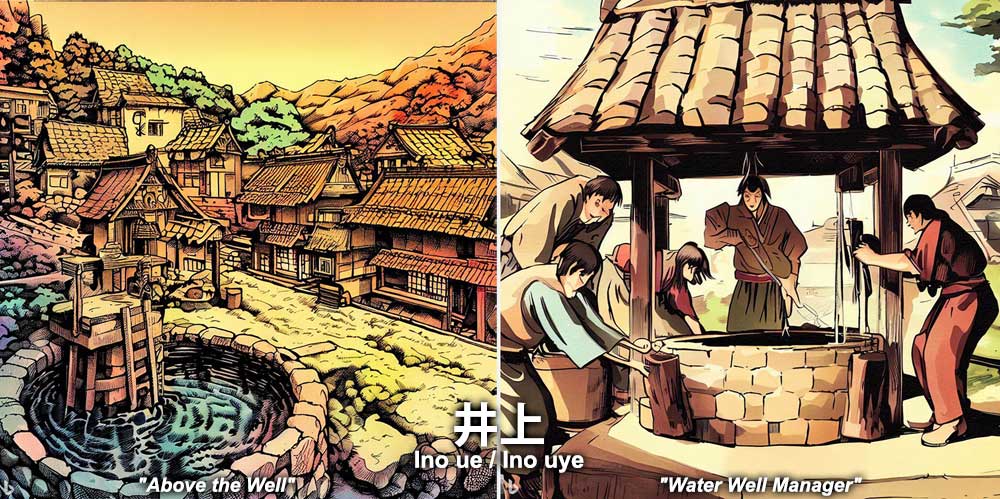

Inoue / Inouye (井上): The water well was very important in the village. The meaning of the name “Inoue” is ambiguous, but there are at least two possibilities. One says it refers to the village situated above the water well.

The other theory says it may be the manager of the water well. “Ue” (up or above) can also mean one’s boss or even the government. So Inoue might have been the manager or caretaker of the water well. An important job.

Matsui (松井): The important water well spawned many “water well” family names. “Matsui” is one. It’s also one of many “matsu” (pine tree) names. Although the “i” literally means “water well,” it might have morphed from the kanji character meaning “here” (居). So “Matsui” might have meant “Pine Tree Here.”

Ishii (石井): One of the most common water well names with “i” (井). This tic-tac-toe kanji indicates the shape of a square well with crossbeam corners as shown in the left image above.

The Ishii water well was maybe in a spot with many stones. Or the second “i” might have been appended only to extend the name to two kanji.

The kanji characters for Ishii may have been originally pronounced “Iwai” now commonly written as 岩井 with a similar meaning. (“Iwa” means rock.) Chiba Prefecture especially has many Ishii. Many places originally named Ishii such as Iwai in Asahi city and the Iwai Coast, Iwai River, and Iwai Shrine in Minamiboso.

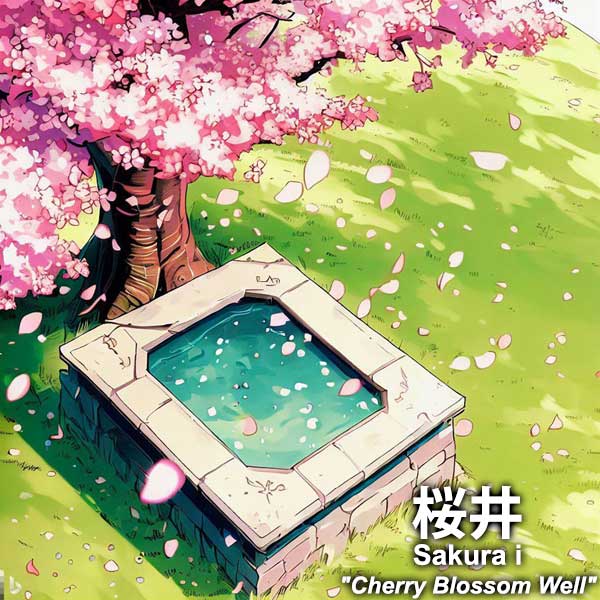

There is also Doi (土井) or earthen well. Other water well names include Matsui (松井 pine tree well), Sakurai (桜井 cherry blossom well), and Fujii (藤井 wisteria well).

Sakurai (桜井): We don’t usually see cherry blossoms growing near a well. Although the “i” literally means “water well,” it might have morphed from the kanji character meaning “here” (居). So “Sakurai” might have meant “Cherry Blossoms Here.”

Fujii (藤井): Wisteria is another revered flower beloved for its tenacity, beauty, and life force. It grows well even in the wild. However, we don’t usually see wisteria growing near a well. Although the “i” literally means “water well,” it might have morphed from the kanji character meaning “here” (居). So the original meaning might have been “Wisteria Here.”

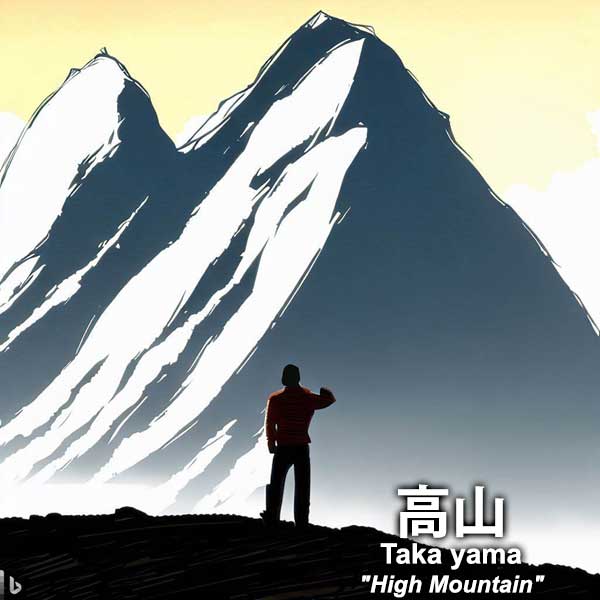

Takayama (高山): “Yama” (mountain) is another natural feature cited by many Japanese names. There’s a wide variety of yama names, reflecting Japan’s many mountains. Japan has many high mountains besides Mt. Fuji which could have inspired this name.

Toyama (遠山): In Japan, mountains can be seen most everywhere, near or far. Toyama no Kinsan made this name famous. Not to be confused with Toyama Prefecture which uses different kanji characters and has a different meaning (富山 Rich Mountain).

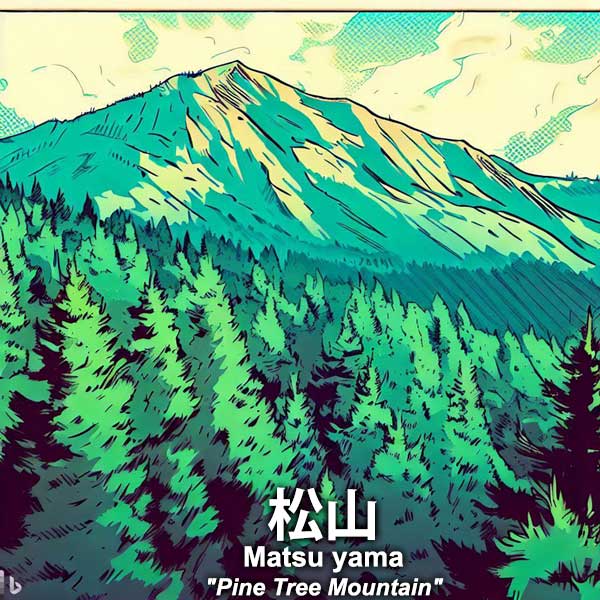

Matsuyama (松山): Another common “yama” name combined with the popular “matsu” pine tree.

Akiyama (秋山): Japan has many autumn mountains. Very pretty.

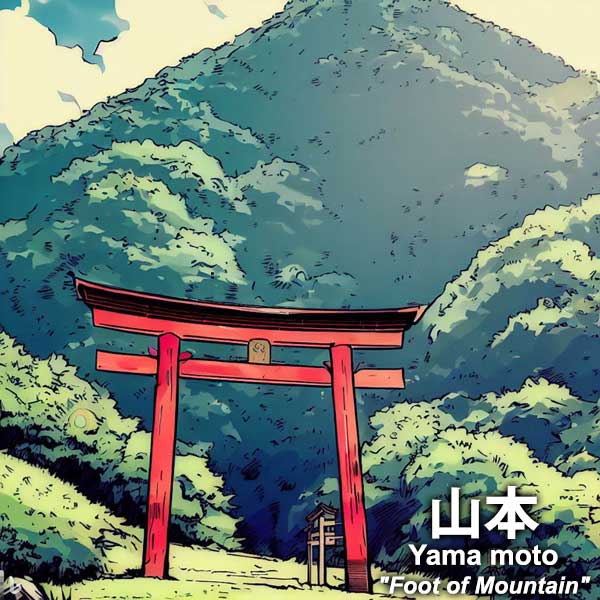

Yamamoto (山本): Yamamoto is one of the most common yama names and it literally means “foot of the mountain.” But “Yamashita” (next image) also has a similar meaning. What’s the difference?

One theory says “Yamamoto” refers to the mountain god which is the mountain itself. So it might refer to the mountain god’s Shinto shrine at the foot of the mountain. There are indeed mountains in Japan with a Shinto shrine at the foot of the mountain dedicated to the mountain god (such as Sanno 山王).

Yamashita (山下): “Yamashita” refers to the village at the foot of the mountain. Living next to a mountain is advantageous because you have easy access to water/rivers, wood, alpine vegetables, and wild game. The foot of a mountain was a prime area to grow rice since there was easy access to water.

Having a mountain behind the village also served a defensive purpose to ward off enemy attacks from behind during periods of civil strife.

I guess Yamamoto and Yamashita people are like neighbors to each other. And since they are such common names in Japan, they reflect the many people who lived next to a mountain in a country mostly covered by mountains (70% to 80%).

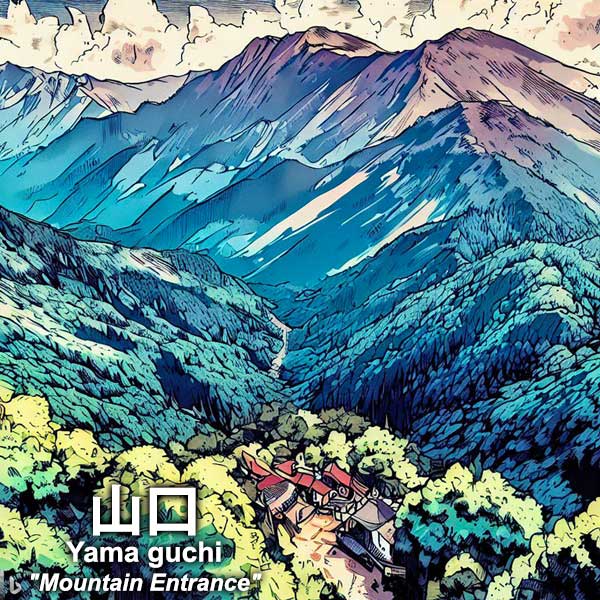

Yamaguchi (山口): Most people assume that this is the entrance to the mountain’s hiking trail. Another explanation says that it refers to the mountain guardian who guarded the entrance to the mountain. Being full of precious resources like wood, vegetables, wild game, etc., the mountain was a sacred place where the gods dwelled.

The mountain guardian vetted visitors to the mountain to make sure they had a legitimate reason to enter the mountain. The most famous mountain guardian was from present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture and they were called “Yamaguchi.” They were a branch family of the Ouchi samurai clan (大内氏) until they were eliminated by Sue Harukata, a vassal of Ouchi Clan in the 16th century. Surviving Yamaguchi clan members then dispersed throughout Japan.

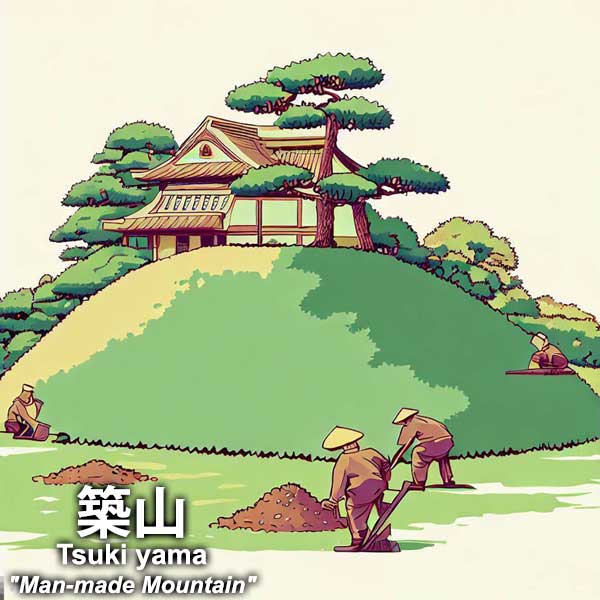

Tsukiyama (築山): “Tsukiyama” has a strong connotation with Japanese garden landscaping. One famous tsukiyama is the miniature Mt. Fuji in Suizenji Garden in Kumamoto, but people are not allowed to climb it. Japanese gardens commonly have a tsukiyama man-made hill which you can easily climb to get sweeping views of the garden. The one in Korakuen Garden in Okayama can be climbed for great garden views.

Hayashi (林): Besides being a family name, it’s also a regular Japanese word for “forest.” One of the basic kanji characters Japanese language learners will first learn. Easy to remember and write.

It also appears in other names like “Kobayashi” (Small Forest), “Obayashi (Big Forest), “Matsubayashi” (Pine Tree Forest), and “Murabayashi” (Village Forest). Hayashi is similar to “Mori” (Woods 森). The difference is that gods dwell in mori, and humans in hayashi.

Like most Japanese surnames, Hayashi has multiple origins. People living in a place named Hayashi or living near a forest may have named themselves “Hayashi.”

It may have also originated from the word hayasu which means to generate or grow (trees, land, etc.). Hayashi might also be descendants of the Rin Clan from China. “Rin” is another pronunciation of the Hayashi kanji character.

Aoki (青木): Like Hayashi, the meaning is straightforward. Japanese language learners should note that although the kanji for Ao actually means “blue,” it means green in this case.

Matsuno (松野): Since “matsu” pine trees are highly favored in Japan, many Japanese family names and place names use it. Pine trees are considered to be sacred because they are evergreen, and so a god is believed to dwell in the pine tree. Pine tree branches are used for New Year’s decorations and for other auspicious occasions.

Matsuno is one of the common “matsu” family names. Very similar to “Matsubayashi” (Pine Tree Forest 松林).

Matsudaira (松平): Pine tree surname similar to Matsuno and Matsubayashi. However, Matsudaira is also the name of a famous samurai clan related to the Tokugawa shoguns. The samurai clan took the name from a place in Aichi Prefecture where there was a nice flatland of Japanese pine trees. No doubt very picturesque.

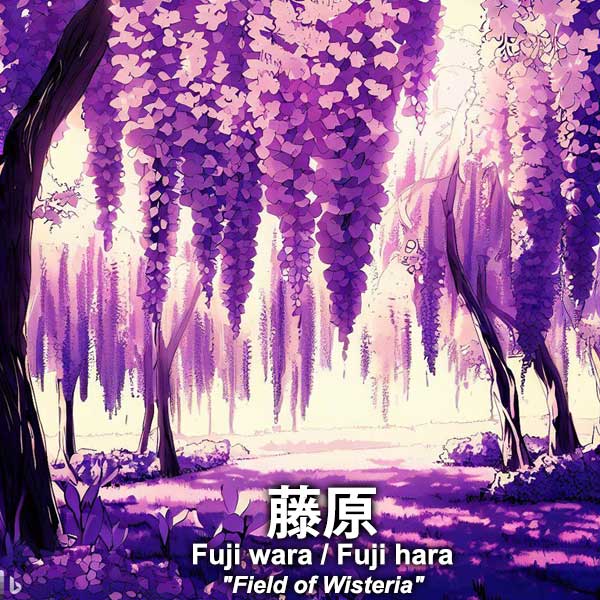

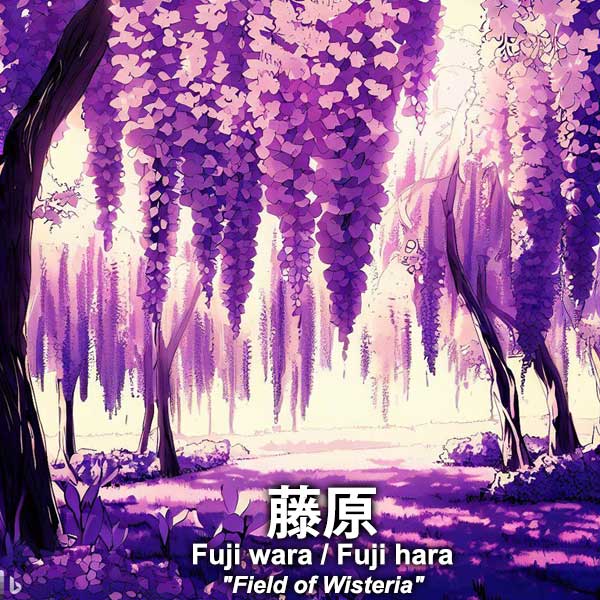

Fujiwara (藤原): “Fujiwara” is one of the earliest Japanese clan/family names. It was bestowed by Emperor Tenji to aristocrat Nakatomi no Kamatari (中臣鎌足) in the 7th century as a reward for his loyal service. He thereby changed his name to Fujiwara no Kamatari. Kamatari thus became the founder of the exalted and influential Fujiwara Clan. The name was inspired by Kamatari’s wisteria garden. “Fuji” means wisteria. Image-wise, the name is very pretty. It can also be pronounced “Fujihara.”

The main line of the Fujiwara came to dominate the Imperial Court and squeezed out the lesser Fujiwara family lines. The lesser Fujiwara then went out to the provinces to better exercise their authority and influence as nobility or military administrators. This spawned many Fujiwara branch families who named themselves after the Fujiwara and the name of their locality or local clan.

For example, Ito (伊藤) was a Fujiwara branch family in Ise (Mie Prefecture). “Fuji” (wisteria 藤) can also be pronounced as “to” or “do.” (Sometimes spelled in English as “toh” or “doh” to indicate a long vowel sound.)

There are many other wisteria family names like Sato (see below), Kato, Saito, Goto, Kondo, Endo, Ando, Kudo, Odo, and Muto. In fact, out of the top 100 Japanese family names today, 10 percent are wisteria names originating from the Fujiwara.

Fujiwara branch families Sato (No. 1), Ito (No. 5), and Kato (No. 10), and are among Japan’s top 10 family names (as of March 2023), but Fujiwara is ironically only No. 48.

This is an example of how important one’s bloodline and family name were regarded in Japan. Forget ability or talent. Status symbol family names and connections was the key to success and advancement especially in politics and government. Today, no one really cares what your family name is unless you’re a direct descendant of a famous samurai. Japan’s most exalted family today has no family name (the Imperial family).

The wisteria is highly favored in Japan for its beauty, tenacity, and strong life force. Its vines can grow around almost anything even in the wild. Often seen in Japanese culture and art. If you want to see a real-life field of wisteria, visit the famous Ashikaga Flower Park in Tochigi Prefecture in April.

Sato (佐藤): Japan’s No. 1 most common family name with about 1.8 million people in Japan named “Sato.” It’s a Fujiwara branch family name combining the first syllable of the family’s locality or occupation and Fujiwara. (“To” is another pronunciation for “fuji.”) The name dates back to the 11th and 12th centuries.

Since there is no definitive historic document explaining the origin of “Sato,” name researchers can only theorize or speculate about the name’s origin based on available circumstantial evidence. The debate centers on the origin of “Sa” and who inspired the name. The first person named “Sato” is known.

The three most discussed possibilities are:

- “Sa” came from “Sado Province” (佐渡), an island in Niigata Prefecture where the Fujiwara served as governor by the 11th century.

- It came from a place named Sano (佐野) in Shimotsuke Province in present-day Tochigi Prefecture where a Fujiwara lived. (Sato is the third most common family name in Tochigi today.)

- “Sa” is from a government job title such as Saemon-no-jo (左衛門尉), a middle management position in charge of guarding the gates of castles and palaces.

Sato name experts believe the most plausible theory is Sado Province where Fujiwara Kin’yuki (藤原公行) served as governor in the early 11th century (佐渡守). (Kin’yuki might not be the correct pronunciation.)

One distinction we must make is that there was the Fujiwara ancestor who inspired the name “Sato” because of his job title, location, etc. But he did not actually rename himself “Sato.” The first person named “Sato” in his honor had to be a direct descendant.

Written records indicate the first Sato was Sato Meizan (佐藤 明算). He had a brother named Fujiwara Kinkiyo (藤原 公清) who is popularly cited as the person who inspired the name “Sato.”

Sato name experts dispute this since it was his brother who was the first to be named “Sato.” Therefore, the person who inspired the name must be in the previous generation, their father or grandfather.

Their father had no connection to any job or place related to “Sa,” but their grandfather Kin’yuki did as governor of Sado island. This argument seems most credible, although nothing is certain.

*Blog post with more details about the origin of the Sato surname: https://photoguide.jp/log/2023/06/sato-japanese-surname-origin/

Source: https://sato.one/origin/

Ito (伊藤): “Fujiwara of Ise” refers to the Fujiwara family in Ise. This Fujiwara family branch started when a Fujiwara descendant in the 9th century became the governor of Ise Province (伊勢守) in present-day Mie Prefecture. Ise is the home of Ise Jingu Grand Shrines, Japan’s most important Shinto shrine dedicated to the Sun Goddess.

Fujiwara descendants in Ise Province named themselves after “Ise” and “Fujiwara” to create “Ito.”

Even today, Ito is the No. 1 most common family name in Mie Prefecture. In nearby Aichi Prefecture and Gifu Prefecture, Ito is No. 3 and No. 2 respectively. Nationwide, Ito is the fifth most common family name in Japan with over a million people so named. After Sato, it is the second most common Fujiwara-related surname.

Kato (加藤): This name combines the “Kaga” (加賀) and “Fujiwara” names. Samurai Fujiwara Kagemichi (藤原景通) had a job title called Kaga-no-suke (加賀介) which was akin to an assistant governor of Kaga Province in present-day Ishikawa Prefecture. His son combined his father’s title with “Fujiwara” to create “Kato.” This was during the Heian Period (794–1185) and exact dates are unknown. After Sato and Ito, “Kato” is the third most common Fujiwara-related surname and the tenth most common family name in Japan.

“Kaga” is also the name of the former province in present-day Ishikawa Prefecture.

Kikuchi (菊地): The chrysanthemum (kiku) is an important flower in Japan because it’s the symbol of the Imperial family. It’s their family crest. You can find the Imperial crest at the Imperial Palace and Shinto shrines (like Meiji Shrine in Tokyo dedicated to Emperor Meiji) connected to the Imperial family.

Be aware that chrysanthemum flowers are also used in funerals and Buddhist temples and on Buddhist altars. Since it is associated with death, don’t bring any chrysanthemums when visiting a sick person in the hospital.

In autumn, we can see exotic varieties of highly crafted chrysanthemums exhibited at shrines, etc.

Shimizu (清水): Pure water is usually associated with natural springs. Even today, people fill up their water bottles at drinkable natural springs open to the public. It’s usually smaller than the pool in the sample image.

In Kyoto, the kanji characters are pronounced “Kiyomizu” after the famous Kiyomizu-dera Buddhist temple.

Ogawa (小川): With many mountains, Japan has many rivers and “kawa” or “gawa” meaning “river” is found in many Japanese family names. Ogawa is one of them. Ogawa family ancestors likely lived near the mountains or rice paddies supplied by river water. Not to be confused with “Big River” (Okawa or Ohkawa 大川).

Ishikawa (石川): Another common river family name. It’s a river with lots of stones. You might wonder how all these rocks got here. It’s usually due to massive flooding carrying the rocks downstream. Most rivers have lots of rocks. Same name as Ishikawa Prefecture.

Ohtani (大谷): When Shohei Ohtani first joined major league baseball in the U.S., there was some confusion over how to spell his last name in English. The English press first spelled it as “Otani.” However, Shohei later made it clear that he preferred “Ohtani.” Why?

Because in Japanese there are two different Otani names which can be spelled and pronounced the same in English. The two different Japanese family names are written and pronounced differently and have different meanings. His name means “Big Valley” which starts with a long vowel “Ō” instead of the short vowel “O” found in the other Otani name meaning “Small Valley” (小谷).

The long vowel “Ō” is commonly spelled as “Oh” to distinguish it from the short vowel “O.” He didn’t want to be mistaken as “Small Valley.” (In Japanese, “tani” can also mean “gorge.”)

The spelling of Japanese names remains a chronic problem, dilemma, and debate. In English, “Ohtani” and “Otani” are pronounced the same and doesn’t make a difference.

There are many place names like “Osaka” and “Oita” having the same long vowel “Ō” but are not spelled as “Oh.” There are also “Big Valley” Ohtani families who don’t mind spelling it “Otani.” The English spelling of Japanese is therefore inconsistent and can be confusing. Must be troublesome for Japan’s passport office where Japanese names must be officially rendered into English.

For personal names, it’s best to respect the person’s English spelling preference.

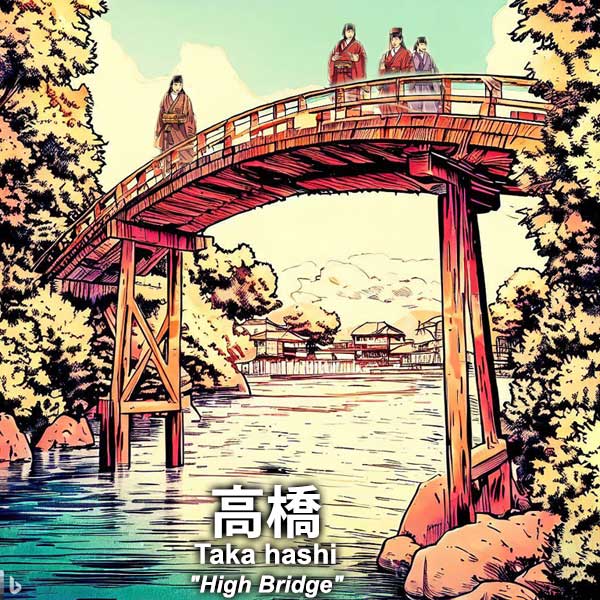

Takahashi (高橋): With many rivers, come many bridges. This is the No. 3 most common name in Japan, and so Takahashi also has a long history and interesting origin which I will later outline in detail in a separate blog post.

Although it is unknown exactly which bridge inspired the name, “Takahashi” appears in a poem in the famous and epic Man’yoshu book of poems from 1,300 years ago. (「石上 布留の高橋 高高に 妹が待つらむ 夜そ更けにける」)

It refers to the Furu-no-Takahashi bridge (布留の高橋) over the Furu River in Furu, Tenri, Nara Prefecture.

The bridge today has a tourist sign citing the poem. It could be the origin of the Takahashi family name, but the current bridge is plain, small, and unimpressive. There’s a small waterfall nearby and in June, you might see fireflies over the river in the evening.

The “Takahashi” name may have originally referred to a bridge crossed by well-dressed, high-ranking nobility. It was also considered to be the bridge where humans and gods crossed. A lofty name indeed. More details later.

There are many other “hashi/bashi” bridge names like Hashimoto (Near the Bridge), Ohashi (Big Bridge), and Ishibashi (Stone Bridge).

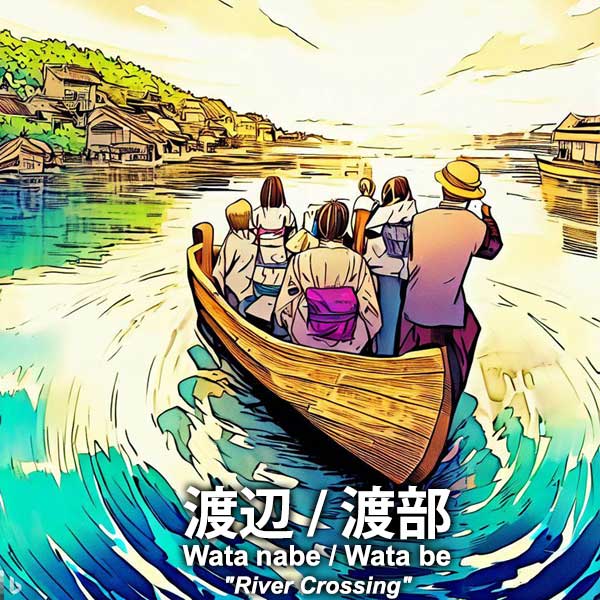

Watanabe (渡辺): Although the word “river” is not in the name, “Watanabe” inherently refers to a river crossing by boat. It may have originated from crossing the Yodo River in Osaka.

If people needed to cross the river and there was no bridge, they rode on small wooden boats driven by a paddler standing on the rear with a long paddle stick.

A rare sight in Japan today, and mainly a tourist attraction. Watanabe ancestors might have been a boat man. “Watabe” (渡部) is a variant of Watanabe and has the same meaning.

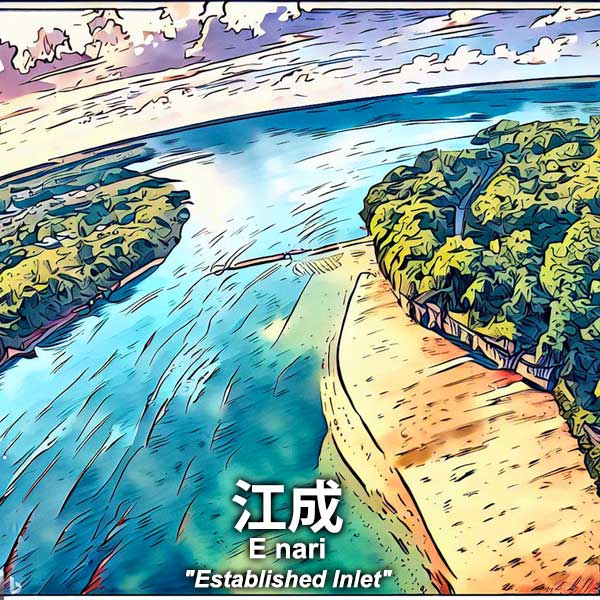

Enari (江成): Not a common name, but it’s an important natural feature for boats to go out to the ocean (or inland sea). The kanji characters for “E” and “nari” are commonly found in Japanese names like “Edo” (江戸) and “Narita” (成田).

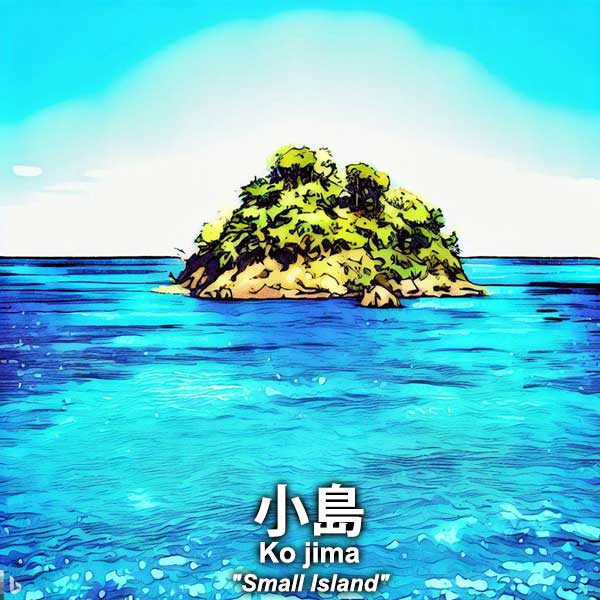

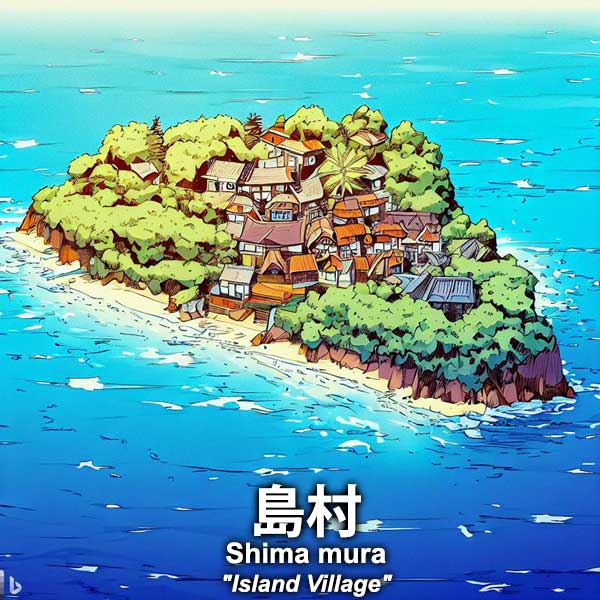

Kojima (小島): Japan has hundreds if not thousands of small islands. Not surprised that this is a common name. Only one of many “shima” (island) names, reflecting Japan as a country of islands. It can also be a small area surrounded by something other than water.

Shimamura (島村): With so many islands, there are many island villages. An island like this is not typical though. Couldn’t get the AI to draw a bigger island with a village.

Note that “shima” does not necessarily mean “island.” It can refer to a separate district or area.

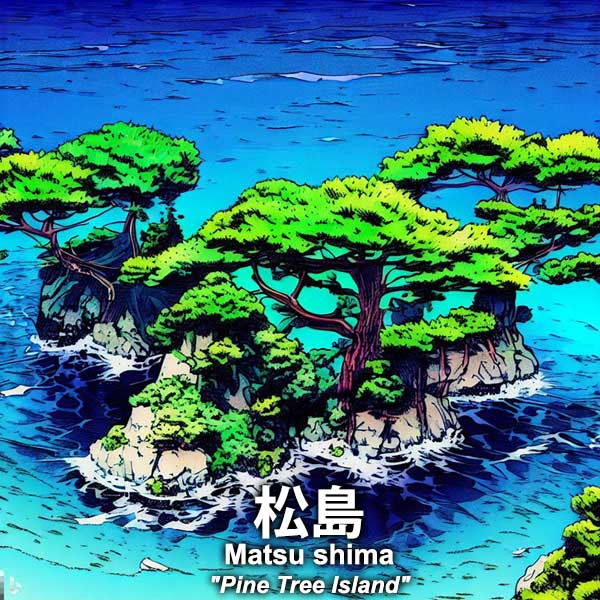

Matsushima (松島): Another picturesque family name. It’s also a place name and major tourist sight in Miyagi Prefecture (near Sendai) and one of Japan’s Scenic Trio (Nihon Sankei 日本三景). Other two being Miyajima in Hiroshima and Amanohashidate in northern Kyoto.

Nakajima/Nakashima (中島): This is typically a small island or sandbar in the middle of a river. Also used as a place name or island name.

Higa (比嘉): Now for a few common Okinawan family names. “Higa” is Okinawa’s No. 1 most common name. “Hi” likely refers to “Higashi” or east. The east is where the sun rises, so the name likely expresses joy (ga) at the sun. Okinawan religion also worshipped a sun god associated with the east.

Kinjo/Kaneshiro (金城): Since Okinawa had many castles (gusuku), there are many castle-related family names in Okinawa. Kinjo (also pronounced “Kaneshiro”) is the most common one. “Kinjo” and “Kaneshiro” are modern spellings/pronunciations of the kanji characters originally pronounced differently in Okinawan.

Oshiro (大城): Oshiro is another very common gusuku (castle) family name in Okinawa.

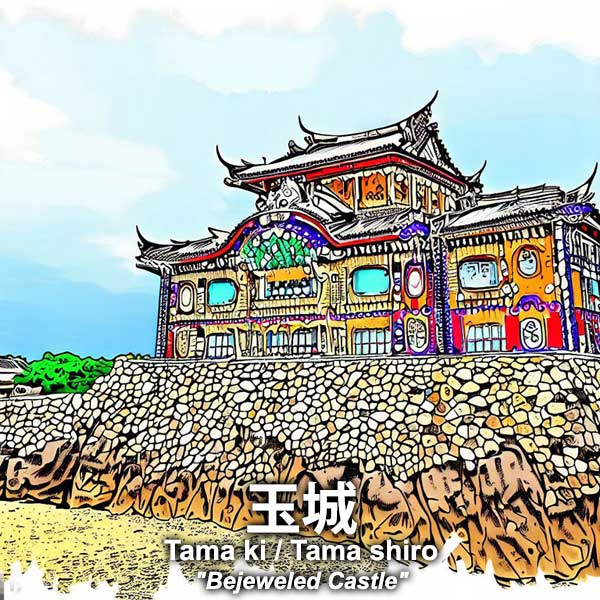

Tamashiro/Tamaki (玉城): If there’s a “Gold Castle,” why not have a Jewel Castle too? A gem amid the sparkling ocean.

Miyashiro/Miyagi (宮城): Another very common castle family name in Okinawa. Remember Mr. Miyagi in the movie “The Karate Kid”? (Karate was invented in Okinawa.)

Shimabukuro (島袋): Although it’s another common Okinawan name, the definitive meaning of “Shimabukuro” remains a mystery. It literally means “Island Bag” which doesn’t make sense. Researchers have come up with some theories.

Maybe it means an island enveloped by the ocean (like a bag). But besides island, “shima” can refer to a village, region, hometown, or even a country. And “bukuro” could be a variant of happiness (fuku) or storehouse (kura). A storehouse contains rice, and food always makes people happy.

And so I came up with an image of happy Okinawans (dancing) with a storehouse included for good measure. I think “Island Happiness” would be a popular meaning among many people. But who knows?

So, hope you enjoyed these illustrated Japanese family names. Although a lot of research has been done on Japanese family names by Japanese researchers, a lot remains unknown. Thanks for reading.

To be continued with more illustrated Japanese family names coming later…

Common words (kanji characters) in Japanese family names:

| 藤 (fuji, to), wisteria 田 (ta, da), rice paddy 川 (kawa, gawa), river 橋 (hashi, bashi), bridge 村 (mura), village 山 (yama), mountain 井 (i), water well, here 島 (shima), island or separate area 本 (moto), origin, root 高 (taka), high 口 (guchi), entrance/exit, opening 原 (wara, hara, bara), field 野 (no), farm field | 木 (ki), trees 林 (hayashi), forest 森 (mori), woods 松 (matsu), Japanese pine tree 岡 (oka), hill 石 (ishi), stone 崎 (saki), cape (peninsula) 谷 (tani), valley, gorge 浜 (hama), beach, coast 里 (sato), hometown, settlement 宮 (miya), Shinto shrine, palace 神 (kami), god, deity 寺 (tera), Buddhist temple 吉 (yoshi), good fortune | 北 (kita), north 西 (nishi), west 城 (shiro, gi), castle 大 (o), big 中 (naka), middle 上 (ue, kami), above, upper 下 (shita, shimo), bottom, lower 長 (naga), long 永 (naga), eternal 黒 (kuro), black 白 (shira, shiro), white 青 (ao), green 福 (fuku), good luck |

Reference sources:

- https://myoji-yurai.net/

- https://mnk-news.net/

- https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXBZO18679650S0A121C1000000/

- English Wikipedia

- 「日本人のおなまえっ! 1 」by Morioka Hiroshi, NHK, 2017, ISBN13: 978-4797673432

- 「日本人のおなまえっ! 2 」by Morioka Hiroshi, NHK, 2018, ISB13: 978-4797673500