T. Enami

by Philbert Ono

|

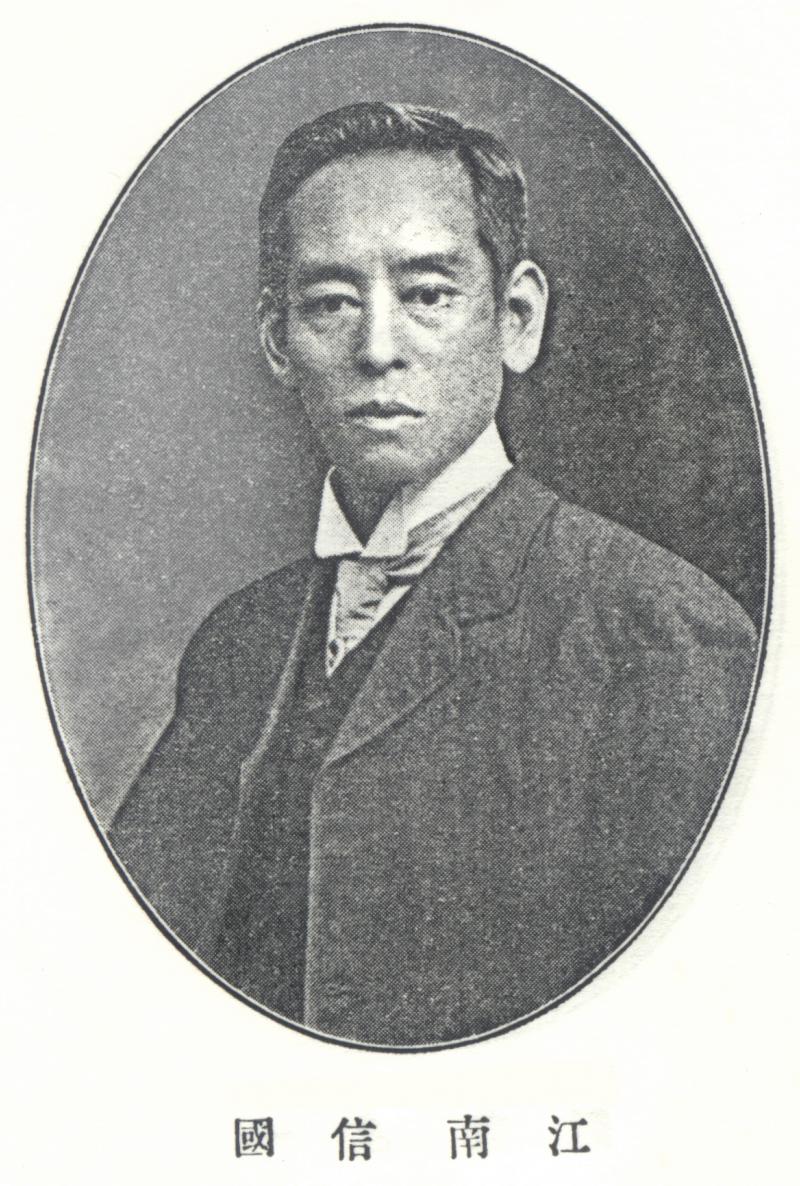

| Enami Nobukuni alias "T. Enami" |

|

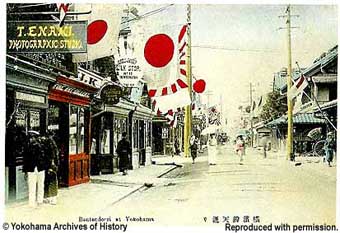

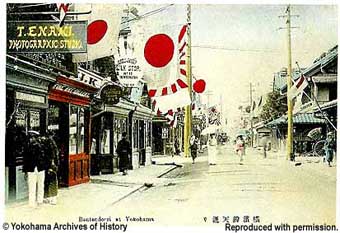

| T. Enami Photographic Studio on Benten-dori |

T. Enami (aka Enami Nobukuni 江南 信國 and Enami Tamotsu 江南 保) (1859-1929) was a professional photographer in Yokohama, Kanagawa.

Operated the "T. Enami Photographic Studio" on Benten-dori street in Yokohama during 1892-1929. Served the foreign tourist market with souvenir photo albums, stereographs, lantern slides, and prints of Japan. He offered numerous scenic views of Japan and portraits of the Japanese. The studio itself was in operation until 1945, taken over by his son.

Born in Tokyo, Enami studied under the famous photographer Ogawa Kazumasa (Isshin) during 1885-1890. He later moved to Yokohama and opened a portrait studio on Benten-dori street in April 1892. He also opened studios in Hong Kong and the Philippines, in Dagupan and Manila. When the Russo-Japan War broke out in 1904, Enami joined the Imperial Army as a military photographer. American publisher T.W. Ingersoll published Enami's stereographs as lithographs in 1905 and sold them in sets of 100 through Sears Roebuck. Enami's images appeared widely overseas, often unattributed to him. Although he was quite prolific and talented, he has been underrated by photo historians. Quite a few of his original hand-tinted lantern slides and stereographs can still be found today.

The studio was destroyed by fire due to the Great Kanto Earthquake on September 1st, 1923. Enami and his family survived, and he reopened his studio on a different lot on Benten-dori by the late 1920s. He managed to rebuild some of his photo stock by acquiring them back from known customers.

When Enami died in 1929, his son 36-year-old son Tamotsu took over. Tamotsu was not a photographer. From 1929 to 1945, the studio focused mainly on photo-processing and printing and publishing. He also continued producing Enami's tinted lantern-slide sets whose images were taken by his father. In 1945, the Enami studio was wiped out again by American B-29 firebombings of Yokohama. Tamotsu did not rebuild the photo stock.

He tried his hand as a photographer, but apparently was not too successful. U.S. Occupation forces occupied parts of Yokohama and he had to move away from Benten-dori. At another part of the city, he restarted his photofinishing business. He died childless in 1969.

For a long time, it was uncertain what the "T" in "T. Enami" stood for. Japanese sources indicated "Tamotsu" as in 江南 保. But there was also another recorded name associated with the T. Enami Photographic Studio which was Enami Nobukuni 江南 信國 who operated the studio until 1926 or so.

Most of us (including myself) assumed that Nobukuni was the father and T. Enami was the son who took over the studio. According to Japanese sources, this made sense chronologically. However, it was strange that "T. Enami" had existed even before Tamotsu was recorded as being an active photographer. This made at least one researcher (in Okinawa) think that Nobukuni and T. Enami were actually the same person, and "T. Enami" was just a trade name. However, when we look at how long the studio was in operation, the period is too long for one person to be active.

This longtime mystery was finally resolved by Rob Oechsle, whom I would call the world's leading collector of T. Enami, especially stereographs. The source of the biographical info above also comes from Rob's findings at his T. Enami Web site.

"T. Enami" was a trade name which apparently suited both Nobukuni and his son Tamotsu. Yes, they were indeed father and son. And also yes, Nobukuni and "T. Enami" were the same person where "T. Enami" was Nobukuni's trade name. Thus, all of us turned out to be only half right (or half wrong). Turns out that "T. Enami" did not stand for "Tamotsu Enami." The "Nobu" kanji character in Nobukuni could also be pronounced as "Toshi," another reading for the same kanji. The "T" really stood for "Toshi." And when his son Tamotsu took over the studio, the "T" could still be conveniently applied. "T. Enami" was used by both father and son as a trade name.

Tamotsu was born six months after Nobukuni opened his T. Enami Photographic Studio. Thus, we know that the studio was not likely named after the son. But he might have purposely named his son with a "T" name so the son could still use the trade name if he took over the studio. Nobukuni's second son (from his second wife) was named Tomojiro (maybe as a backup successor??).

For a detailed biography of T. Enami, see Rob Oechsle's site at http://www.t-enami.org/services . Rob even met Enami's grandson in Yokohama in 2006 who took him to Enami Nobukuni's grave in Tokyo. The grandson had never seem a picture of his grandfather (above), and did not possess any T. Enami images. Guess how he got all this information about T. Enami? He simply looked up all the Enamis (not so many) in a Yokohama phone book, and called the right one.

Vintage Tourist Photos of Japan

This is a magazine article which originally appeared in the Summer 1997 issue (no. 15) of DARUMA magazine which is a quarterly magazine in English covering Japanese art & antiques. This article introduces a collection of hand-colored glass slides produced in the 1920s and '30s by T. Enami, a photographer who operated a photo studio in Benten-dori, Yokohama and catered to foreign tourists. He sold his slides and photos to foreign tourists visiting Japan.

By Philbert Ono and Edward A. Wright

Since

the early days of photography, tourism has been a major contributor to the commercial

success of photography. People like to preserve memories in some physical form

and to tell others about their experiences. Photographs have been serving these

ends very well.

Since

the early days of photography, tourism has been a major contributor to the commercial

success of photography. People like to preserve memories in some physical form

and to tell others about their experiences. Photographs have been serving these

ends very well.

From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, foreign tourists streamed into Japan and bought tourist photographs from local photographers. The photos showed the usual famous sights, the Japanese natives, and Japanese customs. This article examines the work of a Yokohama photographer who sold tourist photographs during the 1920s and 1930s and an American tourist who bought them (her comments also serve as the photo captions).

The Birth of Tourist Photography

Japan finally ended its 250-year isolation in 1858 when commercial treaties

with the U.S. and other countries were concluded. Westerners were then allowed

to reside in treaty ports such as Yokohama, Kobe, and Hakodate. Western photographers

were among those who subsequently came to Japan and set up businesses in these

cities. From the 1860s, Western and Japanese photographers started establishing

portrait studios and catered to mostly foreigners.

Tourists came in droves to see exotic Japan. Photographs and picture postcards became popular souvenirs. Local photographers obliged the demand by selling prints of Mount "Fujiyama," "geisha" girls, rickshaws, cherry blossoms, and other stereotypical images. Such images have been symbols of Japan ever since.

These early photos of Japan usually had English titles inserted within the

image. Although the photos were obviously for tourists, they nevertheless revealed

the dress, look, manners, and scenery of the day.

Tourist photographs were sold mainly as photo albums (containing around 50 photos) for export by overseas visitors. Tourists were eager to tell friends back home about their exotic Far East travels and pictures were perfect for show-and-tell time.

These tourists ironically did a great service to Japan by taking home these early photographs. Japan was destined to meet disaster in the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 and the World War II bombing raids which flattened much of Tokyo and Yokohama, Japan's centers of photography. Many precious negatives and original photographs were inevitably destroyed. Fortunately, however, many of the old photographs survived overseas and Japanese museums and institutions now actively seek their acquisition or "sato-kaeri" (return to one's home). Many of the vintage photos you see in Japanese museums and photo history books today were originally acquired from outside Japan.

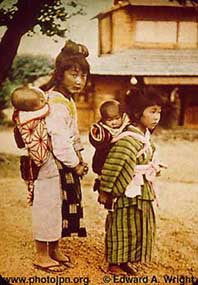

Photo above: "Typical Japanese child in her colorful kimono and parasol - really the Japanese children are like dolls."

"Yokohama

Shashin" and hand-coloring

"Yokohama

Shashin" and hand-coloring

Nagasaki and Yokohama were the cradles of early Japanese photography. Both port

cities had a strong foreign influence and many pioneering Japanese photographers.

Yokohama Port was a major tourist gateway to Japan. The tourist market gave

rise to "Yokohama Shashin" or Yokohama-style photography. This genre

refers to photographs produced by Yokohama's foreign and Japanese photographers

from the 1860s to the 1880s when photography began to spread in Japan. The photographs

were mainly for foreign tourists.

Color photography was not yet invented, and the practice of coloring black-and-white photographs and glass slides by hand became widespread in Yokohama. Hand-colored images became the hallmark of Yokohama Shashin. Hand-colored photographs were popularized by Felice Beato, a well-known Italian photographer who established a photo studio in Yokohama in 1863 and stayed for 21 years.

Japanese pigments were especially well suited for hand coloring photographs.

Hand-coloring became a fine art and large photo studios in Yokohama employed

many Japanese "photo painters." Foreign visitors were astounded with

the work produced by these highly skilled artists. Yokohama's hand-colored photographs

soon became a major tourist export item on par with pottery and lacquerware.

Photo above: "The baby nurses just fascinated me. Each little girl with a baby strapped on her back playing games utterly unconscious of the baby. When I saw this I knew why Japanese children didn't play with dolls. One rarely hears a baby cry in Japan or China and they attribute this to the happy cosy state a baby is in when she is snuggled close to mother, brother or sister. Little boys act as nurses as well as sisters. Some only five or six years old and seem so happy in doing so and they do not seem handicapped in any sport with a baby on their back."

Early technology

Up

to the 1880s, the first tourist photographs were made from glass plate negatives

produced by a troublesome method called the wet collodion process. The photographer

had to coat a glass plate with a photosensitive liquid and the exposure had

to be made within about twenty minutes while the photosensitive coating was

still wet or sticky. After exposure, the wet plate had to be developed before

it dried. Using wet plates required considerable technical skill and the photographer

had to carry the chemicals and a lightproof box wherever he went to take photographs.

(In America, Civil War photographs were taken by this method.) The exposure

time was about 15 seconds. Although it was inconvenient, wet plates enabled

multiple prints to be made from a single negative. This made it commercially

viable unlike the earlier daguerreotype which could produce only one original

photograph.

Up

to the 1880s, the first tourist photographs were made from glass plate negatives

produced by a troublesome method called the wet collodion process. The photographer

had to coat a glass plate with a photosensitive liquid and the exposure had

to be made within about twenty minutes while the photosensitive coating was

still wet or sticky. After exposure, the wet plate had to be developed before

it dried. Using wet plates required considerable technical skill and the photographer

had to carry the chemicals and a lightproof box wherever he went to take photographs.

(In America, Civil War photographs were taken by this method.) The exposure

time was about 15 seconds. Although it was inconvenient, wet plates enabled

multiple prints to be made from a single negative. This made it commercially

viable unlike the earlier daguerreotype which could produce only one original

photograph.

Necessity is the mother of invention, and photography took one giant leap forward with the dry glass plate in the 1880s. The dry plate is similar to modern film except that it has a glass base instead of flexible celluloid. The dry plate could be exposed anytime after it was manufactured and did not have to be processed immediately after exposure. It also had shorter exposure times. Needless to say, it was a godsend to photographers.

Besides prints on paper, photographs were also produced as glass transparencies.

They were usually colored by hand and projected by a "magic lantern"

projector which was a lens-equipped box using an oil lantern as the light source.

The top of the box had a chimney-like opening for the lantern's exhaust. The

oil lantern, which replaced the candle, was later replaced by a gas lantern

and then an electric bulb.

Photo above: "How would our luxury loving ladies enjoy bathing like this? So primitive - The Japanese are very clean people. All bathe at least once a day and many twice. The Chinese say they must be very dirty people because they need to bathe so often."

The early Showa Period (1926-1989)

By the 1920s, photography in Japan was advancing rapidly with the introduction

of film and affordable cameras. Japanese camera manufacturers, camera magazines,

and camera clubs were being started up. Now readily available to the masses,

photography became a popular means of self-expression.

Although tourist photographs were no longer mainstream in the 1930s, the supply and demand still existed. On the supply side was one photographer by the name of "T. Enami" who operated out of a photographic studio on Benten-dori, Yokohama. On the demand side was Mrs. Helen Ford of San Francisco, California.

"T. Enami"

Although this photographer is not particularly well-known, he was brought to

my attention last summer by Edward Wright who saw PhotoGuide Japan and contacted

me. Eddie, who lives in Idaho, had inherited a large collection of hand-colored

glass slides that originally came from T. Enami's studio. He wanted to know

more about Enami. All he knew was that Enami had a studio on Benten-dori in

Yokohama during the 1930s and sold tourist photos.

Photo above: Postcard showing Benten-dori in Yokohama. T. Enami's studio is pictured on the left. Most old photos of Benten-dori show the clock tower (Benten-dori's symbol at the time). It's hard to find a Benten-dori photo not showing it. T. Enami's studio was a distance away from the clock tower so his studio is never seen in old photos and postcards except for the one above. Today, Benten-dori is a quite, narrow street with a few hostess bars. A far cry from the early 20th century when it was a major business and shopping area. The postcard is from the Yokohama Archives of History's Pedlar Collection. Reprinted courtesy of the Yokohama Archives of History.

He sent me prints of some of the glass slides and they piqued my interest immediately. I visited the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography library and the Yokohama Archives of History and did some digging. I found out that "T. Enami" was Tamotsu Enami who inherited a portrait studio from Nobukuni Enami, maybe his father or his real name. Nobukuni apprenticed under Isshin Ogawa, a famous pioneering Japanese photographer who was instrumental in introducing dry plate technology to Japan.

Nobukuni operated a photo studio on Benten-dori Street, Yokohama from 1892 to 1926. His lines of business were listed as "colored lantern slides and stereoscopic views." Then Tamotsu took over the studio in 1926 (or changed his name) and called it "T. Enami Photographic Studio." An old trade directory listed Tamotsu Enami from 1929 to 1938.

There is little else we know about T. Enami. We are thus seeking more information about T. Enami and Nobukuni Enami and would like to get in touch with any other owners of his photographs or similar photographs of this period.

Mrs.

Helen Ford and her Japan collection

Mrs.

Helen Ford and her Japan collection

The collection of more than 200 hand-colored glass slides which Eddie inherited

were collected by a wealthy and well-known San Francisco socialite named Helen

Ford. Mrs. Ford traveled the world extensively during the late 1920s and 1930s.

During the worst of the Great Depression in the 1930s, she visited Japan at

least twice. Her first trip was in the spring of 1933 as part of Theodore Rothman's

lavish "Resolute" World Cruise which departed New York in January

1933. ("Resolute" is the name of the passenger liner.) It was during

this trip she traveled to Miyajima, Kobe, Kyoto, Nara, Nikko, Yokohama, and

Tokyo. In the summer of 1934, she visited Japan a second time.

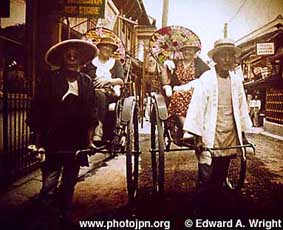

Photo: "Our easiest mode of transportation was by jinricksha. At first we were a little sensitive about using these boys for horses, but when we realized how much they appreciated having the work we learned to know them and really enjoyed riding with them."

The slide collection consists of ready-made tourist photographs of Japan and photographs of her two trips to Japan. The bulk of the collection came from T. Enami. The rest were developed and tinted in the studios of two other photographers: E.H. (Edward Henry) Kemp of San Francisco and to a lesser extent, Bruno Parth of Pennsylvania. It is not clear whether Kemp or his partner and wife Josephine accompanied Mrs. Ford's tour group as a photographer during her first trip to Japan. Mrs. Ford or another photographer may have taken the photographs and simply had them produced later by Kemp or Parth, as both photographers apparently catered to high-society clients.

In the United States, E.H. Kemp is noted for photographs of the American Southwest and Native Americans. One U.S. photo historian, Peter Palmquist was quite surprised to learn of Kemp's Japanese work. Some of the Kemp Japanese slides are apparently much older than Enami's and appear to be studio shots. In another twist of irony, most of Kemp's negatives and equipment were destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 and his best work, taken from 1901 to 1906, survived only in the hands of customers. Although he was able to open his studio several years later, it appears he never fully recovered professionally. It also appears his business failed due to the Depression shortly after he produced the slides for Mrs. Ford.

The glass slides measure 2.5 x 3.5 inches. They were called "colored lantern slides" since they were hand-colored and designed for projection with a magic lantern projector. Most of the slides are in excellent condition since the emulsion is sandwiched by protective glass sheets on both sides. Only a few images have faded badly.

The photographs show people at work and at home, street scenes, flowers and gardens, and the stereotypical images of women in kimono, rickshaws, Mount Fuji, and shrines and temples. They cover the places Mrs. Ford visited in Japan.

Mrs. Ford's husband was George Kidwell Ford, a senior partner in the law firm of Ford and Johnson, on Montgomery Street in San Francisco. Having no children, Mrs. Ford gave the slide collection to her namesake niece shortly before passing away in 1957.

Before her death a few years ago, this niece gave the collection to Eddie's uncle who was a longtime friend. Eddie's uncle gave him the collection--in several boxes unopened for more than 50 years--recently when his health declined. In the boxes were also travelogues and 17 reels of 16mm silent movie film which documents the extensive Rothman tour. The film includes footage of Palestine, Egypt, Morocco, Gibraltar, India, China, Korea, Japan, the Pacific Islands, and other regions and nations.

Photo: My traveling companion, Mrs. James Dempsey (left) of New York, and I in the native costume which we adopted in the heat and I assure you they were very comfortable." (Summer 1934)

Japan

through the eyes of Helen Ford

Japan

through the eyes of Helen Ford

Judging from the photos in Mrs. Ford's collection, the things which fascinated

Western tourists in Japan in the 1930s had not changed much since the late 19th

century. Images of women in kimono (who were all labeled "geisha"),

rickshaws, cherry blossoms, Mount Fuji, and shrines and temples remained the

staple.

Mrs. Ford was simply enchanted with Japan. She was compelled to go on a second trip to Japan in 1934. After returning, she used her slide collection to put together a lantern show for high society circles in San Francisco. She even wrote narration scripts (which were found in collection). A few excerpts from this script are presented in the captions of the photos appearing with this article. During the slide show, she commented that the custom of taking off one's shoes before entering a home or temple was "rather a nuisance." And that samisens were "queer" instruments and the Japanese bride in bridal kimono wore a "queer" hat.

Although Mrs. Ford selected the standard diet of Mount Fujiyama and geisha girl photographs, she also selected a good number of images showing the natives at work. She also liked Japanese children dressed in colorful kimono ("They are like dolls.").

The slide narration opens as follows. Keep in mind that it was 1934 when Japan was on the warpath and the Japanese Empire encompassed much of Asia. And that her presentations were given mostly to high-society women. Despite Japan's militaristic slant, Mrs. Ford was taken by the culture and nature of Japan:

"Japan, the beautiful land of romance, whose emergence from feudalism and its rise to the status of a great power is still the wonder of the modern world, is composed of many islands in the dangerous inland sea. If all these were put together, it would not cover as much space as the state of Texas. Japan is a land of marked beauty and colorful festivals. To me, it was the most fascinating country I visited on my first cruise around the world. I was simply charmed with Japan. And I must admit, I went armed with a prejudice but departed with a great desire to return, which I did last summer. While I would not advise anyone to take her first trip to Japan in summer, it was more than interesting by comparison to me."

Many of us who have visited or lived in Japan and enjoyed the experience can readily identify with Mrs. Ford's enchantment and fascination with Japan. She is only one of many who came before and after her. Although she came only as a tourist, she has inadvertantly left a treasure trove for Japan history buffs. For this, we must thank her and the people who were conscientious enough to store and keep her valuable collection and materials all these years.

Today, the market for tourist photographs taken by professionals is no more. Tourist photography still thrives, but it has changed hands from the professional to the amateur. (The only minor exceptions are picture postcards and those tour group photos in front of famous shrines and temples.) Color film has also killed the painstaking art of hand coloring photographs.

Without a doubt, advances in technology have had a profound impact on photographic culture. However, the human element remains almost the same. Images of Mount Fuji, cherry blossoms, and the geisha girl will continue to emblazon the minds and film frames of tourists for generations to come.

POSTSCRIPT: Mrs. Ford's T. Enami slide collection was donated by the owner in 1999 to the University of Washington's University Libraries (Manuscripts, Special Collections, University Archives) in Seattle, Washington. It is publicly available for non-commercial use as long as proper credit is given.