Climbing Mt. Fuji

Story and photos by Philbert Ono

Note: This article was written some years ago for a magazine and certain information may be out of date.

Since time immemorial, Mount Fuji's majestic and beautiful conical shape has made it sacred in the eyes many awestruck Japanese. Along with geisha girls, torii, and cherry blossoms, it is a timeless symbol of Japan. This is why most people, Japanese and foreigners alike, climb it. (And not because it's there.)

Facts on Fuji

At 3,776 meters (12,395 ft.) above sea level, Fuji-san ("san" means Mt. [富士山]) is Japan's highest mountain. It is on the border between Yamanashi and Shizuoka Prefectures, with the northern half of the mountain in Yamanashi and the southern half in Shizuoka. The crater itself, which is 500 meters across and 200 meters deep, does not belong to either prefecture. The entire mountain is part of Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park. The word "Fuji" is thought to have come from "Fuchi," an Ainu word meaning Deity of Fire.

Fuji-san's present shape was largely created by an eruption around 10,000 years ago. The first recorded eruption occurred in 781. Over 10 eruptions were recorded thereafter, with the last one in 1707. The mountain has laid dormant ever since.

The Japanese have been climbing Mt. Fuji since ancient times, initially for religious purposes. Women, considered to be impure (due to the shedding of blood during menstruation), were not allowed to climb it until 1872. In 1860, the first foreigner made the ascent. He was Sir Rutherford Alcock, a British diplomat stationed in Japan. At first, the shogunate denied him permission to climb fearing for his personal safety. That year, nationalistic Japanese killed his Japanese interpreter and two Dutch captains and burned down the French diplomatic mission. Ii Naosuke, the shogunate's chief minister who favored diplomatic relations with the foreigners, was also assassinated by samurai radicals opposed to foreigners. However, Sir Rutherford later took advantage of the Anglo-Japanese commercial treaty which allowed him to travel anywhere in Japan. He climbed on September 10 (Gregorian calendar) with his Scottish terrier named Toby (also the first dog climber).

Planning the Climb

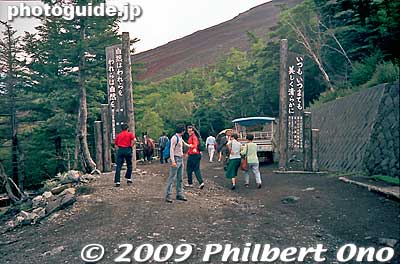

| Entrance to Yoshida-guchi trail at 5th station. |

Each summer, about 300,000 people tromp the trails. First-timers will be delighted at the substantial head start provided by modern roads going up to the 5th station (Go-gome 五合目) halfway up the mountain.

Most people plan the climb to see the sunrise from the summit. The standard plan is to start the climb from the 5th station by early afternoon and spend the night at one of the mountain huts at the 7th or 8th station near the summit. Then wake up at about 3 a.m. to climb to the summit in time for the 5 a.m. sunrise. Climbers can then walk around the crater (taking 60 to 90 min.) before descending.

A recent trend has been for climbers to start the ascent after sunset and rest a few hours at the 8th station near the summit. Then resume the climb to the summit for the sunrise. This makes the trip shorter and avoids sunburn. However, night climbing is colder, pitch-black, and troublesome when you have to hold a flashlight (or get a coal miner's helmet fitted with a flashlight). For first-timers, climbing at night and missing all the lofty scenery cannot be recommended.

Certain precautions and care must also be taken. The lack of oxygen can cause altitude sickness resulting in dizziness, nausea, and shortness of breath. It is important to not overexert yourself. As you start climbing, you should stop and rest briefly whenever you start panting too much. Take longer breaks (around 10 min.) after each hour of climbing. Watch for falling rocks and don't stray from the trail. And if the weather gets really bad, take refuge in a mountain hut.

Also, leave your trash at a mountain hut or take it home.

When to Climb

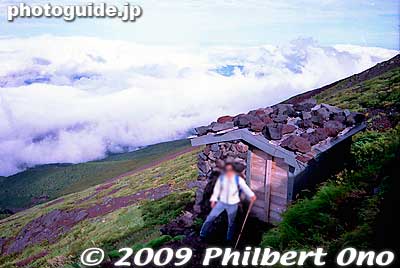

| Mt. Fuji's shadow. |

Although Mt. Fuji is open to climbers year-round, the vast majority climb during the official climbing season from July 1 to August 26. This is when all the public facilities on the mountain are open, including mountain huts and information booths. Public transportation to and from the mountain is also frequent and convenient.

The weather should be a major consideration as to when to climb. Late July to early August is the best time weather-wise when the wind and rain are minimal. Unfortunately, this is also the most crowded period. The trails become jammed with people in an endless, continuous line moving slowly (or not at all) up to the top. The mountain huts are also packed like sardines. People and musty futons are laid everywhere, even in the dining area.

Due to the notorious crowding, we decided to avoid the peak period and take a chance on the weather by climbing at the end of August right after the official climbing season. Although most mountain huts close after August 26, a handful remain open until early September or October. If you don't like crowds, don't go between late July and mid-August. If you don't like getting drenched by rain and wind, go during the peak period and bear the crowds. Keep in mind that fine weather is never guaranteed on Mt. Fuji.

What to Wear and Take

The temperature on Mt. Fuji is about 20˚C lower than in Tokyo. Therefore in summer, the temperature on the mountain would be around 10˚C and somewhat lower at night and at higher elevations. Your clothing should include an undershirt, a long-sleeve shirt, a sweater, a windbreaker, gloves, long pants made of durable material, thick socks, hiking boots covering your ankles, and a raincoat. A cap and sunglasses are advisable for protection from the sun. A compact camera, penlight (or a large flashlight if you're climbing at night), and a map (preferably made of plastic) of the mountain would also be nice to have.

Since the mountain huts provide meals and bedding, you only need to take water (about 1.5 liters), a few light snacks and sweets, change of clothing, and toiletries. A can of disposable oshibori (moist napkins) would also come in handy for a sponge bath. Put everything in plastic bags and pack them in a nylon rucksack, preferably waterproofed. Pack your things to minimize trash and weight. Discard any unnecessary paper or plastic packaging.

Climbing Routes and Getting There

| Hut roofs are weighed down with rocks. |

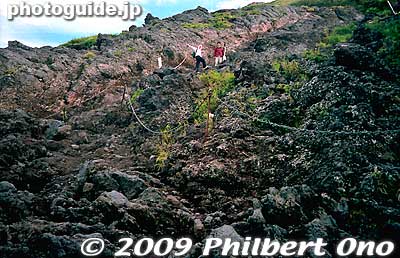

| Rocky trail |

How you should get to Mt. Fuji will depend on which trail you decide to ascend. There are six trails to make the ascent or descent. The starting point of four of the trails is halfway up the mountain. The other two trails start at the foot of the mountain.

Most climbers ascend one of two trails: the Kawaguchi-ko-guchi route (which merges with the Yoshida-guchi route 吉田口) or the Fujinomiya-guchi 富士宮口 route. For Tokyoites, the former is the closest and shortest route, and for people west of Mt. Fuji, the Fujinomiya-guchi route is convenient. Both routes start about halfway up the mountain.

One major advantage of the Kawaguchi-ko-guchi (or Yoshida-guchi) route is that you can see the sunrise even if you don't reach the summit. Climbers on the Fujinomiya-guchi route on the western slope must reach the summit in order to see the sunrise. During the peak period, getting to the summit in time for the sunrise may be a problem due to the slow-moving line of climbers crowding the route.

From Tokyo, the Kawaguchi-ko-guchi route can be reached by taking the Fuji Kyuko bus at the Shinjuku Nishi-guchi bus terminal. The bus goes directly to the route's 5th station (go-gome), taking two and a half hours if the traffic is smooth. You can also take a train from Shinjuku Station to Kawaguchi-ko Station taking slightly over 2 hours. From Kawaguchi-ko, buses go up the Fuji Subaru Line toll road to the 5th station, taking 55 minutes. The 5th station is already 2340 meters above sea level and above the clouds.

The Fujinomiya-guchi route is accessible by bus from Mishima Station on the Tokaido Line (taking 2 hours) and from Fujinomiya Station on the Minobu Line (1 hr. 45 min.). If you take the shinkansen, get off at Shin-Fuji or Mishima Station. Note that most buses run only during the official climbing season.

Each trail is divided into "stations" (gome). The fifth station (go-gome) and New fifth station (shin-go-gome) are about halfway up the mountain and accessible by car and bus. Most people start or end their climb here. Few people start at the 1st station at the very bottom. One confusing thing about Mt. Fuji is that there are two 5th stations and three New 5th stations. Same names but very different locations. So if you hear "go-gome" or "shin-go-gome," confirm which one. Perhaps you could distinguish them by mentioning the trail (i.e., Kawaguchi-ko-guchi go-gome).

For the descent, the Subashiri-guchi route and the Gotemba-guchi route are popular. Both are sliding-sands trails with loose gravel which can easily go inside low-ankle shoes. The Subashiri-guchi trail ends at the new 5th station and the Gotemba-guchi trail ends at another new 5th station. There are buses which go to Gotemba Station from both new 5th stations.

Lodging

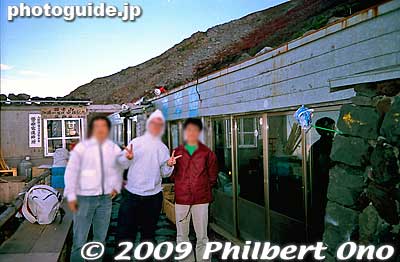

| Mountain hut. |

| Communal bunk bed in mountain hut. |

There are mountain huts (yama-goya) at one station or another on each trail and on the summit. After deciding which trail to climb on and your climbing schedule, decide where (usually the 5th or 8th station) you want to spend the night. For lodging reservations and more information, call (in Japanese) the Tourist Section of the Fuji-Yoshida City Hall at (0555) 22-1111 or the Fujinomiya Tourist Association at (0544) 27-5240.

Do not expect luxury accommodations nor much privacy in the stone huts. Everything is communal, even the sleeping quarters where damp futon bedding are lined up right next to each other. The food is adequate but not filling. During the peak period, make reservations by 3 p.m. on the day you plan to check in.

Ironically, water is the most precious commodity on the mountain where it rains frequently and where certain brands of mineral water come from. Mt Fuji has no rivers nor streams since all the rain water is absorbed by the cinder cone and percolates downward. Although the huts collect rainwater for non-drinking purposes, there is no piped-in water. This means that there is no clean water to take a bath, brush your teeth, wash your face, clean your contact lenses, etc. You will have to use your own precious drinking water or buy bottled water at the hut. The toilets are the squat type with no sewage system. The smell is not so bad since it's too cold for the bacteria to multiply.

The only creature comforts are electricity (supplied by a generator) and telephone lines. TV and radio stations can also be received. In July 2008, docomo announced that FOMA (3G) mobile phones can be used on Mt. Fuji during the peak climbing season. (For other carriers, check with them yourself.)

The people who run the huts live in the huts during the climbing season. They do take baths with gas-heated water. But the water and gas supply is not enough for the hundreds of people lodging in the hut.

Guess how all the provisions are brought up to the mountain huts? No, not by helicopter. By bulldozer. On a detailed hiking map of the mountain, you can see a bulldozer trail zig-zagging up the mountain from the new 5th stations. As you climb up or down, you may notice the bulldozer trail with bulldozer tracks. As we were descending, we saw a bulldozer making its way up. The operator's compartment was completely covered by a canvas.

The Climb

| Trash on Fuji. |

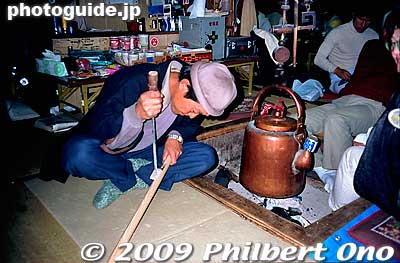

| Branding my walking stick. |

| Goraiko sunrise as seen from Fuji-san. |

| A rainy Mt. Fuji summit. |

One summer on August 29, I and two other friends left the Shinjuku Nishi-guchi bus terminal at 7:45 a.m. on the Fuji Kyuko bus for Kawaguchi-ko-guchi go-gome. The bus was supposed to arrive at 10:10 a.m., but a traffic jam caused by a highway accident delayed the bus by 2 hours. The 5th station at Yoshida-guchi had a large parking lot, lodges, restaurants, and shops which sold raincoats, walking sticks, mineral water, and other hiking gear. After lunch, we started the climb at 2 p.m. Although it was drizzling off and on when we arrived, it turned out to be a nice, fair day on the mountain.

The trail started off with a wide, level path. Then all of a sudden, the trail slanted upward and had us huffing and puffing. It took about 40 minutes to reach the 6th station. We rested on benches near a mountain hut appropriately named "Sea-of-Clouds Lodge." The view over the clouds was marvelous. The 6th station was where the Kawaguchi-ko-guchi route merged with the Yoshida-guchi route which started at the foot of the mountain. Tourists with no time or energy to climb all the way up can just hike to the 6th station and return to the 5th station.

After the 6th station, it got quite strenuous. There was some zig-zagging and later the trail got rocky and steep. I had to rest for a minute or two every so often. A brief rest worked wonders for overworked lungs. The air was thinning and altitude sickness had to be avoided at all costs.

On the uncrowded trail, we greeted a few foreigners, elderly people, and children going up or down. We even saw people who were climbing the mountain alone (not recommended). As we were going up, the people descending told us, "ganbatte!" (Keep going!). True words of wisdom. But we later found out that we had to do more than just "ganbatte."

The trail was surprisingly clean. I had expected unbelievable littering. I found out later that the trail was cleaned up by mountain hut operators, tourist association members, and city officials every day during the peak period.

We finally reached our mountain hut at the 8th station, the springboard to the summit. Although we had climbed for only 3 hours, it seemed like we had climbed all day long. As the sun went down, the mountain's shadow was cast on the clouds (another photo op).

Our mountain hut, called Toyokan (東洋館), could accommodate 500 people. It was a low-profile, long-house structure. Only a handful of people were staying there that night. For dinner, we were served hamburger steak, vegetables, miso soup, and slightly crunchy rice (not enough water to cook it). Including breakfast and dinner, it cost 6,000 yen a night. I had my walking stick branded with hut's insignia for 100 yen. Branding your walking stick at each station is popular among climbers. It proves that you were there. I had an interesting talk with the hut manager and his young female assistants. They supplied much of the interesting information for this article.

That night, we could see the clouds glowing under the moonlight and the pretty lights of the lakeside towns below. I went to the toilet and took a sponge bath with a can of disposable oshibori. We went to our bunks at 9:30 p.m. The sleeping quarters had two-level, continuous bunks. We could hear the whistling wind as we fell asleep.

At 4:45 a.m. the next morning, one of the female assistants came and woke us up for the goraiko (literally, the coming light 御来光) due in 15 minutes. We had decided to view the sunrise from the mountain hut instead of the summit. We awoke to a faint orange glow on the horizon above the clouds. It soon got more intense and the sky got brighter until finally the familiar round ball appeared. It was a beautiful sunrise.

Breakfast was just two large riceballs. I supplemented the meal with Calorie Mate energy bars. We left for the summit at 6 a.m. amid strong winds and rain. The weather was miserable. As we climbed upward, the wind blew downward. Added to that was the steepness of the trail, the thin air, and the colder temperature. All my prayers for good weather went unanswered. The scenery was blocked by cloud cover and the ground was barren rock and gravel. The vegetation disappeared at the higher elevations.

Except for the mountain huts we passed by, everything was either cloud white or lava black. It took us 3 hours to reach the summit, about twice as long as normally required. We were the only ones there. All we saw were boarded-up mountain huts, benches, rain, and fog. The wind and rain were at its worst. I jumped up and had the wind blow me away a few feet. Walking around the crater rim was out of question. The crater was hidden by thick fog and we couldn't see anything. How unfortunate. It would have been nice to walk around the crater and see Sengen Shrine, the weather observatory, a few hills, and the crater itself.

We started descending at 9:30 a.m. via the Subashiri route. Almost as soon as we started the descent, we were relieved of the wind and rain that battered us for so long. The descent was rapid and the summit soon towered above us. The gravelly trail was wide and soft. (Reminding me of the Sliding Sands Trail on Haleakala on Maui in Hawai'i.) Although going down was much easier, it was still tiring on the leg muscles since you have to brake yourself with each step down the steep, sliding slope. Along the way, I picked up the few soft drink cans and plastic bottles littering the trail. When my large plastic bag got full, I emptied it at the next mountain hut.

It took us 3 hours to reach the Subashiri-guchi new 5th station, the end of the trail. Almost everything was soaked, my rucksack, jacket, pants, and squishy shoes. If you take a camera or a mobile phone, be sure to keep them in a waterproof bag. My cheap 500 yen poncho was torn apart by the wind. There was a mountain hut called Fuji-sanso where we had lunch. Since buses were infrequent, we called a taxi to take us to Gotemba Station. The taxi ride took about 35 min. and cost us ¥6,000 which we split three ways.

Conclusions

Although we often see children and the elderly climbing Mt. Fuji, making it look easy, don't be misled. Though it is far from impossible, it's not a piece of cake. And it's not for everyone. If you have asthma or a cold, or if you disdain physical hardship, panting, roughing it, or physical and mental discomfort, forget it. But if you're the adventurous type and want to climb a grand symbol, do it. If you're a photographer, do it. I climbed it before the age of digital cameras, so I could not take as many photos.

Some people climb Fuji-san repeatedly, but for me, once is definitely enough. The experience has changed my view of Mt. Fuji forever. Now, whenever I see Mt. Fuji or a picture of it, I think of my climb and a sense of satisfaction creeps in from having been there and done that. At the same time, it remains as one of my most unforgettable experiences in Japan.

- See more photos of the Mt. Fuji climb here.