Last additions - Hawai’i's Nikkeijin Matsuri—Oshogatsu and Bon Dance Last additions - Hawai’i's Nikkeijin Matsuri—Oshogatsu and Bon Dance |

After seeing the exhibition, you might want to stop by the neighboring Yokohama World Porters shopping mall and get a malasada from Leonard's in the Hawaiian Town section.It might be crowded though, especially on weekends/holidays.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Back of the exhibition flyer.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Museum's exhibition flyer.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Page 4 talks about the nisei soldiers and bon dance held on six islands.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Page 3 gives a history of bon dance in Hawai’i. Lower part explains New Year's worship at Shinto shrines in Hawai’i.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Page 2 of the newsletter gives an overview of the exhibition. Lower article describes New Year's preparations in Hawai’i.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Cover of the museum's newsletter (Winter 2016 issue) publicizing the "Hawai’i's Nikkeijin Matsuri—Oshogatsu and Bon Dance" exhibition.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

The back of the exhibition room has this small viewing room for video screenings of "Great Grandfather's Drum" about Maui Taiko (led by Kay Fukumoto) and a condensed documentary video by Jun'ichi Suzuki about the nisei vets."Great Grandfather's Drum" (57 min.) is screened every day of the exhibition at 10 am and 2 pm. Suzuki's film (40 min.) is shown every day at 11:30 am and 3 pm. Suzuki will also give a one-hour talk at the museum on Jan. 14 at 2 pm. Free admission, no reservations required.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

100th Infantry Battalion nisei's cotton khaki shirt and garrison cap. From Saburo Ishitani. Also, a 442nd RCT nisei soldier doll (nicknamed "Yoshi" or "Tak") made in 2000 and sold by a toy store in Portland, Oregon.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Military medals, badges, and patches from Saburo Ishitani of the 100th Infantry Battalion.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Aloha shirt for 100th Infantry Battalion veterans with a Japanese and Hawaiian design. The design includes torii, Japanese castle, shamisen, pagoda, pineapple, Gion Matsuri float, and "One Puka Puka" (100).Below are military medals, badges, and patches.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Large showcase displaying Iwakuni Ondo implements and nisei soldier artifacts.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Tenugui hand towels often worn or used by bon dancers.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Lyrics to the Iwakuni Ondo "Nisei Soldiers" song about the 442nd RCT composed by Mune Ozaki.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Top photo is some of the soldiers in the 100th Infantry Battalion at Camp McCoy in Wisconsin.Bottom photo are 100th Infantry Battalion soldiers taking a short break in Menton, France in 1944.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Upper left shows a Hawai’i Hochi newspaper (April 2, 1943 issue) with Japanese announcements of the successful enlistment of nisei individuals in the military.Each announcement is from the soldier's parents and siblings addressing their local community (like Wahiawa).

Lower left shows Hawai’i Hochi newspaper (May 12, 1943 issue) listing the names of Hawai’i's nisei who have volunteered to enlist in the military (total 2,645).

Right photos show the 100th Infantry Battalion training at Camp McCoy in 1942.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Corner dedicated to nisei soldiers.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Places on the Big Island that hold a bon dance.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Places on Maui that hold a bon dance.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Places on Oahu that hold a bon dance.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Places on Kauai that hold a bon dance.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

The back of the exhibition room was this large cloth panel listing all the places (mostly Buddhist temples) on each island that hold a bon dance.Upper right photos are of Waialua Hongwanji on Oahu and lower left photos show Daifukuji Soto Mission in Kona.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Newspaper articles about James Kunichika from July 24, 2004 and Aug. 1, 2003.One is online: http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2004/Jul/23/il/il01a.htmlDec 24, 2016

|

|

Showcase had more exhibits about Iwakuni Ondo with an umbrella, happi coat, and tenugui hand towel from the Iwakuni Odori Aiko Kai.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

"Sakuma Teicho" lyrics.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Video of James Kunichika singing an Iwakuni Ondo song called "Sakuma Teicho" about Tsutomu Sakuma, the brave commander who died when his submarine that sank off Yamaguchi Prefecture in 1910.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Bon Dance Panel 8 - Iwakuni Ondo Aiko Kai and James KunichikaIn the 1920s, an Iwakuni Ondo group was formed. They obtained a taiko drum and other implements and started practicing for public performances. Such a group played an important part in having the Iwakuni Ondo survive in Hawai’i.

In 1951, popular Honolulu bon dance singer James Kunichika (1915–2012) formed the Iwakuni Odori Aiko Kai fan club together with taiko drummer Goichi Fukunaga. (Kunichika was born on Kauai and moved to Honolulu. Iwakuni was his mother's hometown.) At the time, it was Oahu's only official fan club for the Iwakuni Ondo. It was composed only of Yamaguchi Prefecture immigrant descendants. From the 1980s, their membership increased dramatically. By 2000, they had over 200 members. The Honolulu mayor and Lieutenant Governor at the time were also members.

The Iwakuni Ondo's lead singer has to memorize long Japanese lyrics lasting 10 to 15 min. So it was important to train the younger generations. By the mid-1990s, Japanese-speaking nikkei in Hawai’i were almost gone and Kunichika was practically the only bon dance lead singer on Oahu who could sing in Japanese.

Kunichika made efforts to train the non-Japanese-speaking sansei as successor singers. He also worked hard to perpetuate and sustain the Iwakuni Ondo on the neighbor islands.

For his efforts and accomplishments, he received numerous awards including the Living Treasure Award from the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawai’i and the 2003 Pan-Pacific Festival Silversword Award.

Panel photos: Top is Iwakuni Ondo Aikokai soon after it was formed. Bottom is Kunichika (second from left) at home teaching Iwakuni Ondo to a few younger people.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Bon Dance Panel 7 - Iwakuni Ondo, a Case StudyOf the many bon dance songs used in Hawai’i, there are songs that remained while others disappeared over the years as the times changed. What were the factors that caused the songs to remain or disappear?

Iwakuni Ondo is one of the three bon dance music genres that remain in Hawai’i. It is performed live with the singer on the yagura tower holding up an umbrella and singing a song having seven-and-five syllables. Many of the songs expressed the passionate emotions of the Japanese people. The songs included Japanese historical episodes and war stories such as Nikudan Sanyushi (Three Human Bullets 肉弾三勇士, about three heroic Japanese soldiers who sacrificed themselves while blowing up enemy lines in Shanghai in 1932) or Sakuma Taii Monogatari (Sakuma Teicho 佐久間艇長 or 佐久間大尉物語 about Tsutomu Sakuma, the brave commander who died when his submarine that sank off Yamaguchi Prefecture in 1910). Such songs are still popular in Hawai’i today and the yonsei and gosei have learned the story even if they don't understand Japanese. A taiko drummer at the bottom of the yagura accompanies the singer and sets the beat. The dancers dance clockwise, spinning their arms elegantly.

Most immigrants from Yamaguchi Prefecture came from specific regions so they had a strong hometown affinity among themselves. From the early 1900s, they formed hometown associations according to their village or town. These associations were later unified by the Yamaguchi Prefecture Kenjinkai Association formed in 1926. To reinforce their hometown unity, they held picnics, movie screenings, concerts, stage performances, and bon dances.

After the war, new Iwakuni Ondo songs were created. They were about Hawai’i. One song called "Nisei Soldiers" (ああ第442部隊) was about the 442nd RCT composed by Mune Ozaki to memorialize them. This song was often sung during the nisei's heyday in Hawai’i.

Panel photos: Top is James Kunichika singing Iwakuni Ondo on the yagura at a bon dance in 2001. Bottom photo is dancers dancing to the Iwakuni Ondo at a bon dance.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Bon Dance Panel 6 - Bon Dance Songs Still in UseThe songs played at bon dances in Hawai’i are either recordings from CDs or tapes or performed live. Recordings include modern ondo songs like Tanko-bushi and Pokemon Ondo. New recorded songs are also added every year. Songs performed live have a deep connection to the specific prefecture from where immigrants hail.

In 1924 when Japanese immigration was banned, the Japanese population in Hawai’i was 125,361. Most of them came from (in order of the highest number): 1. Hiroshima, 2. Yamaguchi, 3. Kumamoto, 4. Okinawa, 5. Fukuoka, 6. Niigata, 7. Fukushima, and 8. Wakayama. Of the five prefecture-specific bon dance songs that were performed in Hawai’i until the postwar years, only three of them have survived: Iwakuni Ondo (from Yamaguchi), Fukushima Ondo (from Fukushima), and Eisa (from Okinawa).

Table shows the number of immigrants from each prefecture and their percentage in the Japanese population in Hawai’i (same order as listed above from 1 to 8). Right column shows the five prefecture-specific bon dance music genres that they practiced.

Panel photo shows Eisa drummers at the Okinawan Festival at Kapiolani Park in Honolulu in 2013.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Bon Dance Panel 5 - Bon Dances Held on Six Hawaiian IslandsIn Hawai’i, bon dances are held from June to September. During this time, a bon dance is held somewhere every weekend. (Unlike in Japan when it is held at the same time in mid-August.) The bon dance schedule is announced in May in local newspapers like the Hawai’i Herald and online.

In 2016, bon dances were held at 83 locations on six Hawaiian islands (33 on Oahu, 27 on the Big Island, 8 on Kauai, 13 on Maui, 1 on Molokai, and 1 on Lanai).

Almost all bon dances in Hawai’i are held at a Buddhist temple. A few temples even hold a lantern floating ceremony (toro nagashi). A bon dance memorial service is held before or after the dance, giving the dance a strong religious connection.

Panel photos: Top photo is a bon dance at Hawai’i Jodoshu Betsuin, bottom left is the Hawai’i Herald newspaper (Hawai’i's Japanese American Journal), bottom right is the 2016 bon dance schedule published by the Hawai’i Herald.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Bon Dance Panel 3 - The Resurrection of Bon Dance After the WarWhen the Pacific War broke out, cultural activities by the Japanese immigrants were banned. No more bon dances.

It wasn't until the summer of 1947 when a bon dance was finally held again. It was a fundraiser for a war memorial.

In 1948, bon dances saw a full-fledged ressurrection. In 1951, the biggest bon dance was not at a Buddhist temple, but at Ala Moana Park in Honolulu. It was held jointly by nisei veterans clubs (100th Infantry Battalion Veterans, 442nd Veterans Club, MIS Veterans Club, and 1399th Veterans Club). The postwar bon dances were held to memorialize the war dead.

Panel photo: Top photo is a July 1947 Hawai’i Hochi newspaper ad for a bon dance to raise funds to build a memorial. Bottom photo is a Hawai’i Hochi newspaper article about the 1951 bon dance held jointly by nisei veterans clubs. Headline says there were 2,000 dancers and 30,000 spectators.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Bon Dance Panel 4 - From Bon Odori to Bon DanceIn the 1950s, Hawai’i's Japanese community shifted from the issei to the nisei and the "bon odori" began transforming into a Hawai’i-style "bon dance."

Bon dances got infused with new songs based on Hawai’i's lifestyle and Hawai’i-themed songs composed in Japan. The old "Hole-hole-bushi" song sung by Japanese laborers in the sugar plantations got a new version composed by Japanese composer Raymond Hattori in 1957 at Columbia Records in Japan. In the 1960s, Buddhist bon dance songs like Bukkyo Odori, Daishi Ondo, and Shinran Ondo were also introduced. Likely due to the bon dance's strong connection with Buddhist temples. ("Bukkyo" means Buddhism, "Daishi" is an honorific title for a Buddhist sect's founder, and "Shinran" is the name of the founder of the Jodo Shinshu Sect.)

Even today, the bon dance is the largest social gathering of nikkei in Hawai’i. Even without understanding the Japanese language, young and old alike can dance to Japanese songs and enjoy the bon dance. Originally, the bon odori was for the Japanese to reaffirm their Japanese identity. After the war, it has become an event reflecting Hawai’i's melting pot. Today, we often see people from other ethnicities enjoying the bon dance.

Panel photos: Top photo is a bon dance food stand at Kona Hongwanji on the Big Island. Bottom photo is a bon dance at Lahaina Jodo Mission on Maui showing non-nikkei dancers.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Bon Dance Panel 2 - The Beginning of Bon Dance in Hawai’iThe bon dance likely had its beginnings in Hawai’i at the sugar plantations in the late 19th century. Feeling nostalgic, Japanese immigrants from the same region of Japan would get together and reenact the bon dance from memory.

In the early 20th century when Buddhist temples were built within the plantation camps, the bon dance started to be held at the temples. From the late 19th century, the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Sect (Nishi Hongwanji) started full-scale propagation in Hawai’i, and other Japanese Buddhist sects also came to Hawai’i. By 1906, there were over 30 Buddhist temples in the sugar plantations on all the major Hawaiian islands.

In the beginning, people from a specific prefecture held their own bon dances. Eventually, the bon dance was held by Japanese immigrants from different prefectures. Their mindset changed from being prefecture-specific to a more collective Japanese mindset. Their culture evolved accordingly.

Panel photo: Sugar plantation workers in late 19th or early 20th century.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Bon Dance Panel 1 - The Japanese in Hawai’iHow did the Japanese culture and lifestyle continue in Hawai’i up to today?

The Japanese was originally the largest ethnic group, accounting for over 40% of Hawai’i's population. This percentage began to shrink from the 1930s with the influx of other ethnic groups. By Dec. 1941, they still accounted for 37% of Hawai’i's population. According to the 2000 US Census, they comprised 20% of Hawai’i's population. Today, they are still a major ethnic group in Hawai’i.

By the early 1900s, as much as 70% of sugar plantation laborers were Japanese immigrants. Hawai’i's sugar industry saw explosive growth as it catered to the world market. There was a major labor shortage so they brought in cheap laborers from overseas starting with the Chinese. Later Japan and the Kingdom of Hawai’i signed the Kanyaku Imin agreement which allowed Japanese to emigrate to Hawai’i from 1885.

The early immigrants who worked on the sugar plantations as contract laborers had planned to make money in Hawai’i and return to Japan as rich men. They did not intend to live in Hawai’i permanently. The early Japanese immigrants lived together in their own plantation camps. People from the same hometown or prefecture would form an association and help each other. This lifestyle contributed to the transference of Japanese New Year's traditions and the bon dance to Hawai’i.

Panel photo: 1885 Kanyaku Imin contract for an immigrant named Otsuki.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Hawai’i Kotohira Jinsha omamori with an American flag design.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Hawai’i Dazaifu Tenmangu and Hawai’i Kotohira Jinsha omamori.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

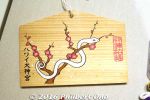

Hawai’i Dazaifu Tenmangu and Hawai’i Kotohira Jinsha ema tablet.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Hawai’i Izumo Taisha omamori including one for Sports and Marathon.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Hawai’i Daijingu omamori. The right one is for Shichi-go-san (Coming of Age) for 3 and 7-year-old girls and 5-year-old boys.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Hawai’i Daijingu ema tablet for the Year of the Snake.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

On the left are Hawai’i Daijingu omamori and ema tablets. On the right are Hawai’i Ishizuchi Jinja omamori.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Cover of the 2014 New Year's party program by the Honolulu Japanese Chamber of Commerce.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Honolulu Star-Advertiser article (Jan. 1. 2014 issue) about mochi traditions.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Program for the New Year's Eve and New Year's Day services at Honpa Hongwanji Betsuin in Honolulu.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

New Year's programs and newspaper article from the collection of Noriko Shimada.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

The table showcase displaying New Year's newspaper ads for Oshogatsu sales by Japanese supermarkets in Hawai’i.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Other New Year's photos taken at various Shinto shrines in Hawai’i by Noriko Shimada.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Oshogatsu Panel 5 - New Year's CelebrationsNew Year's celebrations continue throughout January among the Japanese-American community in Hawai’i. They're mostly held by Japanese cultural organizations.

The Honolulu Japanese Chamber of Commerce holds a New Year's party attended by about 400 people. The reigning Cherry Blossom Queen and six princesses also attend the party.

The party features iconic Japanese things like a red torii and kadomatsu at the ballroom entrance and Cherry Blossom Princesses waving a sacred Shinto wand over the attendees. The party's highlight is the humorous performance of the "Shoko Shiranami Gonin Otoko" (Shiranami Five 白浪五人男) kabuki play in English played by local businessmen. They have been performing this same play at this party every year since 1946. It's a buffet and they do not serve traditional New Year's osechi.

Panel photos: Top photo is two Cherry Blossom Princesses waving the sacred wand at the ballroom entrance under a torii, bottom photo shows the "Shoko Shiranami Gonin Otoko" play at the New Year's party.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Oshogatsu Panel 4 - New Year's Prayers at Shinto ShrinesBefore the war, Hawai’i had 60 Shinto shrines. Praying at a Shinto shrine during New Year's was a very important ritual for the Japanese immigrants. Today, Hawai’i has only seven Shinto shrines. Four in Honolulu (Hawai’i Izumo Taisha, Hawai’i Daijingu, Hawai’i Kotohira Jinsha combined with Hawai’i Dazaifu Tenmangu, and Hawai’i Ishizuchi Jinja), two on Maui (Maui Jinsha and Maalaea Ebisu Kotohira Jinsha), and one on the Big Island (Hilo Daijingu, Hawai’i's oldest Shinto shrine). A few of the shrines do not have a resident priest. Even today, praying at Shinto shrines during New Year's is a widely known Japanese custom in Hawai’i.

Hawai’i Izumo Taisha sees over 10,000 worshipers on New Year's Day alone. Recently, a Japanese TV program did a story on this shrine so now even tourists visiting from Japan are starting to pray here for New Year's. The shrine has about 30 different kinds of amulets (omamori) such as for finding a marriage partner, safe childbirth, warding off bad luck, etc. It also sells omamori from Izumo Taisha in Shimane, Japan.

New Year's is the biggest event at the other Shinto shrines in Hawai’i as well.

Panel photos: Top is Hawai’i Izumo Taisha on New Year's Day, bottom left is Dazaifu Tenmangu on the left and Hawai’i Kotohira Jinsha in the center, bottom center is Hawai’i Daijingu selling amulets, bottom right is New Year's at Hawai’i Ishizuchi Jinja.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Oshogatsu Panel 3 - Mochi Pounding (Mochitsuki)In Hawai’i from late Dec. to New Year's, Japanese Americans pound mochi mainly at private homes, Buddhist temples, and Japanese cultural organizations.

The Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i in Honolulu holds its Ohana ("Family" in Hawaiian) Festival every New Year's where they pound mochi. They also use this occasion to introduce other traditional Japanese things like taiko drumming, traditional Japanese dance, and kimono. It is to perpetuate Japanese culture to the younger generations.

Ringing in the New Year at Buddhist Temples (Joya no Kane)

Buddhism in Hawai’i has also been modified to suit Hawai’i. This is evident in the way they celebrate the year's end and New Year's. On New Year's Eve, members gather at the temple for a New Year's Eve service. Some temples also ring the bell before midnight.

At Honpa Hongwanji Betsuin in Honolulu on New Year's Eve, they hold a service with a sermon in English and Japanese. After the service, the congregation line up outside to ring the bell. Each person rings it once. The ministers stand nearby and shake hands with the members after they ring the bell. Then they gather in the social hall downstairs to enjoy soba noodles, black beans, and sake. It's interesting that they mix the soba noodles with saimin.

Panel photos: Top left is mochi pounding at the Ohana Festival, top right is Japanese calligraphy at the Ohana Festival. Bottom photo is temple bell ringing at Honpa Hongwanji.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Oshogatsu Panel 1 close-upDec 24, 2016

|

|

Oshogatsu Panel 2 - New Year's PreparationsFor the Japanese and nikkei in Hawai’i, buying food and other things for New Year's is an important custom. To have everyone go out and buy the same things in preparation for New Year's reinforces their Japanese identity. Let's see what they sell for New Year's in Hawai’i.

At Nijiya Market, a popular Japanese supermarket in Honolulu, they sell New Year's merchandise like rice for making mochi, sake, soba noodles, soba broth, kinako, anko, kirimochhi, otoshidama envelopes, round mochi (kagami mochi), chopsticks, naruto, kamaboko, and date-maki (sweet rolled omelette). For osechi meals, they sell black beans, tazukuri sardines, kinton, fried egg, and kobumaki.

In Hawai’i, a popular members-only supermarket called Marukai imports food and merchandise from Japan. At the end of the year, the store is full of New Year's food especially osechi dishes. Almost like a supermarket in Japan.

Don Quixote has daily necessities, clothing, fish, meat, a bakery, medicines, and a Japanese food section. It also sells kadomatsu bamboo decorations, round mochi, and osechi dishes like lotus root and gobo.

Panel photos: Top is Nijiya, lower left is Marukai, and lower right is Don Quixote.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Oshogatsu Panel 1 - History of Japanese New Year's in Hawai’iBefore WWII, the Japanese immigrants (mostly sugar plantation workers) were free to practice their own culture and religion so they celebrated Oshogatsu and other traditional Japanese holidays. However, the war changed all that as the Japanese immigrants were viewed as associates of the enemy. Japanese community leaders were arrested and detained. Japanese language schools, Buddhist temples, and Shinto shrines were shut down and dissolved. Using the Japanese language in public was banned, and gatherings of 10 or more Japanese people were prohibited. Therefore, the Japanese immigrants could no longer hold their festivals like Oshogatsu.

However, after the war, these restrictions were lifted and Japanese immigrants could again celebrate New Year's by visiting temples and shrines, pounding mochi, etc. We can see how their New Year's traditions developed in Hawai’i.

Panel photos: Upper left photo is Hawai’i Daijingu Shrine in Honolulu during New Year's, upper right is mochi pounding at Kahului Hongwanji on Maui, lower left is New Year's decorations at a Japanese American's home (Stephanie Ohigashi), lower right is a family at home having ozoni soup for New Year's (Stephanie Ohigashi).Dec 24, 2016

|

|

The room also has showcases displaying artifacts.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

The right wall has exhibit panels explaining about New Year's (Oshogatsu) in Hawai’i.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

The left wall has exhibit panels explaining about bon dance in Hawai’i.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

With mostly panel displays and some artifacts, this special exhibition explains New Year's customs and bon dances in Hawai’i in layman's language in Japanese.It is a good primer for the average Japanese to gain an understanding of Japanese culture in Hawai’i. Much of the text is based on research conducted by Japan Women's University professor emeritus Noriko Shimada whose specialty is American history. She wrote a thesis about the Iwakuni Ondo in Hawai’i so the bon dance section is dominated by Iwakuni Ondo. Photos were contributed by a number of people including Noriko Shimada, Stephanie Ohigashi, Caroline Miyata, and Ai Iwane.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Medium-size exhibition room for the "Hawai’i's Nikkeijin Matsuri—Oshogatsu and Bon Dance" (ハワイの日系人のまつり -お正月とボンダンス-) exhibition.Unfortunately, the exhibition has no English explanations so I've created a quick translation of all the panel displays on this web page. (It's not an official translation nor a word-for-word translation, but still very accurate.)Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Entrance to the special exhibition room.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

Museum entrance.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

The Japanese Overseas Migration Museum (JOMM) in Yokohama held a special exhibition titled, "Hawai’i's Nikkeijin Matsuri—Oshogatsu and Bon Dance" (ハワイの日系人のまつり -お正月とボンダンス-).Held from Dec. 23 to Feb. 12, 2017, the exhibition was about New Year's and bon dance in Hawai’i. Free admission (Open 10 am–6:00 pm, enter by 5:30 pm, closed Mon.). The museum is a 10-15 min. walk from JR Sakuragicho Station or 10-min. walk from Bashamichi Station (Minato Mirai Line). Exhibition web page: http://www.jomm.jp/events/2016/index.html#bon

Map: https://goo.gl/maps/D1T2H9LpfSoDec 24, 2016

|

|

JOMM is Japan's largest museum dedicated to Japan's overseas emigration history and experience.It is operated by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) which is Japan's Peace Corps. There are permanent exhibitions explaining the immigration to Hawai’i, continental USA, and other countries especially South America. There are also changing or special exhibitions. The museum also has a reference library (closed on Sun.) with a collection of 20,000 books and materials about Japan's immigration.Dec 24, 2016

|

|

|

|

|

|